Dada South?

Experimentation, Radicalism and Resistance

December 12, 2009–February 28, 2010

Iziko South African National Gallery

Curators:

Kathryn Smith

Roger van Wyk

Assistant Curator:

Lerato Bereng

Texts accompaniments sourced from exhibition panels and related ephemera.

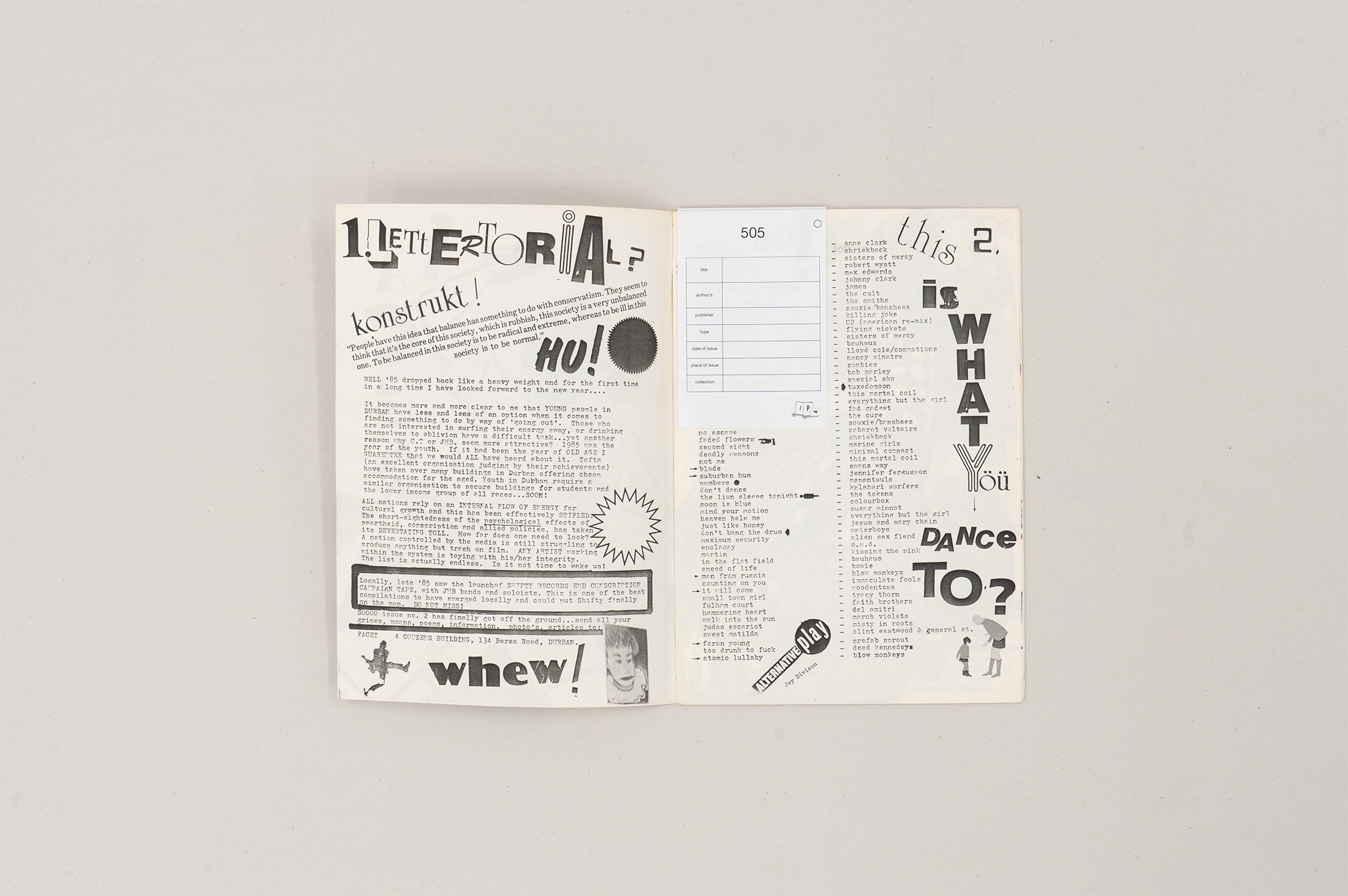

Exhibition and event credits listed in full in page footer.

Editor:

Alana Blignaut

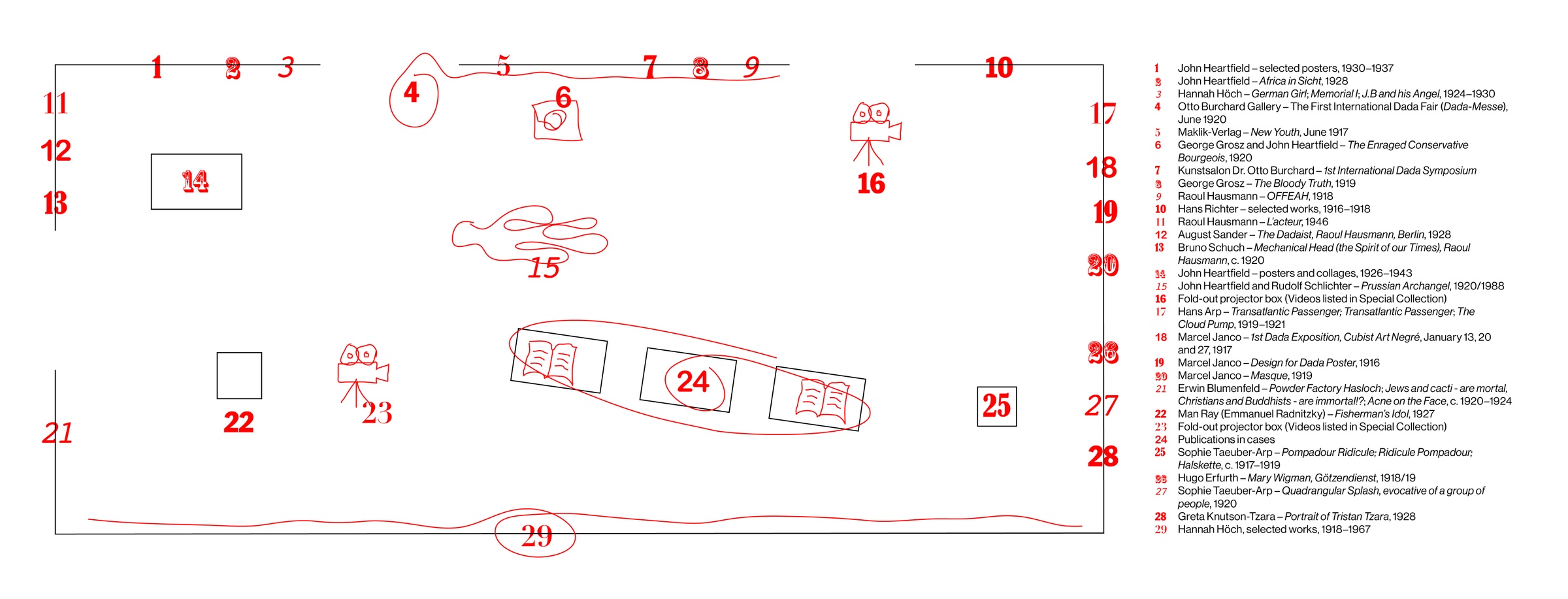

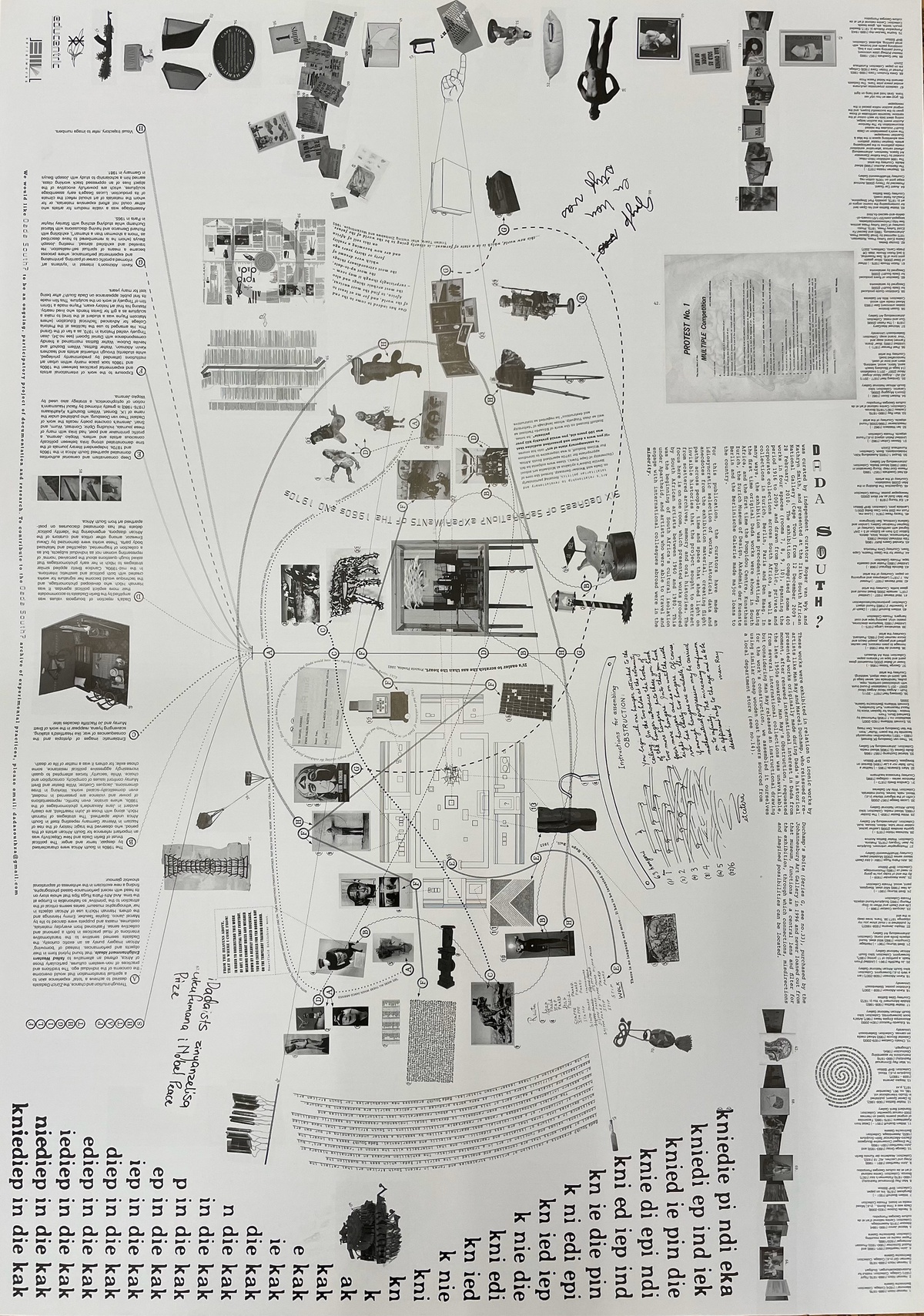

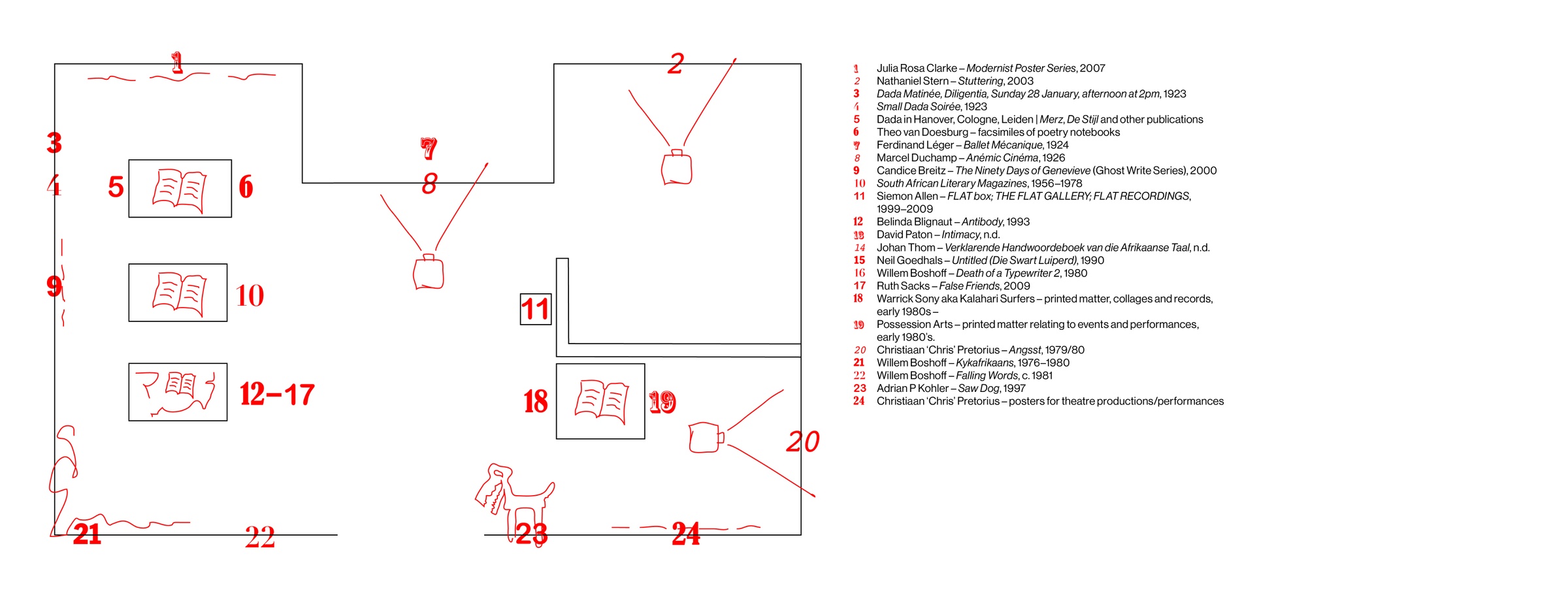

Exhibition maps designed by Ben Johnson.

“The hours that hold the figure and the form

Have run their course within the house of dream.”

– Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street (1928)

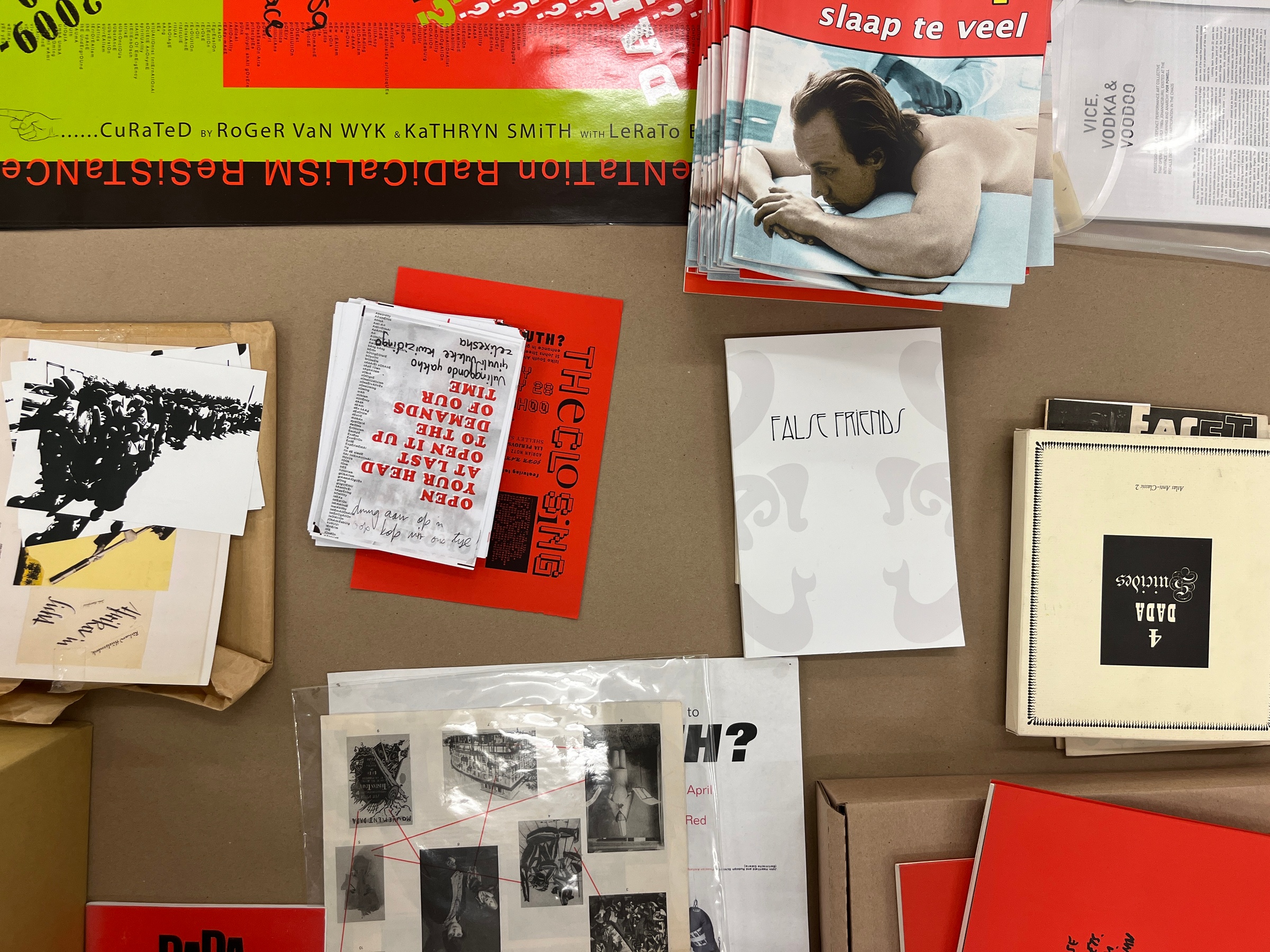

A week-long intensive in the Reading Room sees curators Kathryn Smith and Roger van Wyk unpack an archive of material accumulated during the research and design of Dada South? Experimentation, Radicalism and Resistance, an exhibition that was held at Iziko South African National Gallery, December 12, 2009–February 28, 2010.

This reflective ‘sorting’ in 2024 continued a series of momentary unpackings and interactions with the Dada South archive taking place at A4 since 2019 (as an example, francis burger and Jonah Sack engaged components of the archive during Papertrails in 2022).

Continuing the enquiry into the affordance and meaning of the archival afterlives of contemporary art initiated by engagements with this archive, A4’s digital custodian Alana Blignaut takes on the role of editor to digitise and compile an online publication of Dada South? A noteworthy and influential exhibition in South Africa, Dada South? hosted artworks from international collections in Berlin, Paris and Zürich, alongside an extensive selection of works by local artists from the 1960s to 2010.

Reviewing the exhibition’s archive after a 14-year interval asked for a conscientious attention to detail, openness to errantry and frank discussions about the values practitioners bring to the table in reconstructing the context and felt quality of the subject matter. Distilled into a digital resource over the following year, this rendition of Dada South?'s content hopes to foreground the ways exhibition histories can help signal possibility rather than simply nostalgia.

Situating this particular exhibition within broader enquiries into experimental arts practices by the curators and others (see selected bibliography below), it becomes evident that Dada is (to rephrase Benjamin) pivotal to understanding the role of the arts in broader philosophical critiques of modernity and its unequal and asymmetric distribution in colonial expansion and totalitarian regimes. What emerged during this workshop was a need to be particularly sensitive to how Dada’s double-edged strategy of enchantment and disenchantment relate to, reconfigure and/or amplify similar narratives in modernity as a whole.

In our attempts to wrestle life-affirming strategies like freedom of thought from the complex heritage of art locally and elsewhere, we need perhaps hold Dada’s twin legacies of utopianism and cynicism more lightly. Indeed, the Dadaists seemed always to be anticipating their own end, even as they reached for alternative ways of being and becoming. (Alana Blignaut, 2025)

–

A4's Reading Room is an adaptable space attached to A4's Library and Archive. Intended to solve for form depending on its required function, it is at once a book-ish environment for reading and contemplation and a place to unpack artists' archives. The Reading Room's inter-leading doors become walls when locked to create a stand-alone spatial research studio that hosts residents and practices site-specific work that most-often is connected to packing and unpacking projects as a form of research.

Jane Alexander, Siemon Allen, Hans Arp, AS IS, Kevin Atkinson, Avant Car Guard, Johannes Baader, Bridget Baker, Wayne Barker, Walter Battiss, Deborah Bell, Willie Bester, Belinda Blignaut, Erwin Blumenfeld, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Willem Boshoff, Candice Breitz, Susan Bristow, Brendon Bussy, Norman Catherine, Kathy Coates, Christo Coetzee, Jacques Coetzer, Steven Cohen, Barend de Wet, Aletta du Toit, Neville Dubow, Marcel Duchamp, Marc Edwards, Carl Einstein, Paul Éluard, Max Ernst, flatinternational, Kendell Geers, Josh Ginsburg, Neil Goedhals, George Grosz, Gugulective, Stacy Hardy, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Emmy Hennings, Matthew Hindley, Nicholas Hlobo, Stephen Hobbs, Hannah Höch, Robert Hodgins, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, Wopko Jensma, William Kentridge, Lisbeth Kkwadi, Yves Klein, Greta Knutson-Tzara, Adrian P Kohler, KOOS, Donna Kukama, Andrew Lamprecht, Moshekwa Langa, Andre Laubscher, Fernand Léger, El Lissitzky, Michael MacGarry, Ashnath Makubila, Sanna Mokgaha, Brett Murray, John Nankin, François Naudé, Gimberg Nerf, Christian Nerf, Dimitri Nikolas-Fanourakis, Eduardo Paolozzi, Cate Paputla, David Paton, Malcolm Payne, Francis Picabia, Peet Pienaar, Possession Arts, Chris Pretorius, Andrew Putter, Jo Ractliffe, Lesego Rampolokeng, Man Ray, Julia Raynham, Robin Rhode, Hans Richter, Julia Rosa Clark, Tracey Rose, Athi-Patra Ruga, Ruth Sacks, Rudolf Schlichter, Joachim Schönfeldt, Kurt Schwitters, Lucas Seage, Rosemarie Shakinovsky, Robert Sloon, Warrick Sony, Nathaniel Stern, Paul Stopforth, Rolf Streuber, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Johan Thom, George Tobias, Tristan Tzara, Chaz Unwin, Hentie van der Merwe, Theo van Doesburg, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Ian Waldeck, Wolf Weinek, Robert Weinek, Emmett Williams, Ed Young, Asha Zero.

It's easier to scratch the ass than the heart.

– Francis Picabia, 1921

It is nearly a century since Dada first touched the central nerve of Western culture, attacking its logic, denouncing its ideas of community and nationhood, and demanding total freedom of thought. One of Dada’s primary revolutions is the reinvention of art as a form of tactics. Seen in this way, their work represents the origins of many of the forms we see in contemporary art. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Dada attitudes found refreshed expression in Neo-Dada movements such as Fluxus, Arte Povera, the Situationist International and Pop Art, which preceded and deeply influenced Minimalism and Conceptual Art. It was in the 1960s that these ideas began to filter into South African art.

Dada South? presents a collision of artistic strategies and forms that reflect the impact of Dada; works that are conceived and enacted in the spirit of Dada, which seek to question the conventions, values and function of art in a troubled society. The exhibition surveys an alternative history of resistance in a culture of isolation and repression, one that intersects with the canon of ‘resistance art’ but which deviates into forms that are less didactic, more eclectic and experimental. In the recuperation of these lesser-known histories, Dada South? proposes new vocabularies for South African art.

South African art is often thought to suffer from an ‘anxiety of influence’ from Western artworld centres. Part of this perception is a poor understanding of our own art history. Dada South? intends to invert this by asserting South African practice as part of international art history; acknowledging a range of remarkable artistic positions that have called upon Western influences selectively, even randomly, to develop local, indigenous responses to specific conditions of South African history.

A major part of this process is about recuperating lost histories, practices and experiments. It is difficult to tell this story, as many works produced in a radical spirit were temporary interventions. They were not necessarily intended as art objects in the traditional sense and certainly not expected to be purchased by museums for future preservation. As such, many such gestures exist only as oral histories and anecdotes that are occasionally backed up with an ephemeral document, like a poster, photograph, flyer or newspaper article found during an archival hunt.

(Source: Exhibition panel)

Dada stood for freedom. Art may be useless but it is also indispensable.

– Michael Kimmelman, 2006The only thing that doesn't die is money, it just leaves on trips.

– Francis Picabia, 1920I applaud all ideas, but nothing else, only the ideas interest me and not what gravitates around them, profiting from ideas disgusts me. "One has to live," you tell me? You know as well as I that our existence is short compared to the profit one can gain from an invention; we're on the earth since the day before yesterday and we'll die tomorrow.

– Francis Picabia, 1921The art market has expanded exponentially and has been losing its shape to achieve monstrous proportions. It is so bloated at the core that it doesn’t seem able anymore to digest all the data. Today it is difficult to imagine anything that could be excluded from art…it has grabbed anything that could be used for its own purpose... Art has finally fulfilled the program of Dada with a vengeance, embedding art into life. The only thing left for art to do is ‘auto-dissolve’… Forget art then. Unless it is capable of bringing us up to the next paradigmatic shift, as Andy Warhol once did, forgetting about its own name and past history. Artists themselves may have been showing the way by venturing so far astray from home. All it would take is to cut off the umbilical cord that still ties art to the market.

– Sylvère Lotringer, 2009

☞ Take Dada Seriously, it's worth it!

The Dada movement was founded in 1916 in the midst of World War I. Drawn to the neutrality of Switzerland, a group of exiled intellectuals and artists from neighbouring countries responded to a public call from Hugo Ball, inviting artists of ‘whatever orientation’ to make contributions ‘of any kind’. They converged in Zürich at the Cabaret Voltaire, a small avant-garde theatre café which opened on February 5, 1916.

The Cabaret Voltaire…has as its sole purpose to draw attention, across the barriers of war and nationalism, to the few independent spirits who live for other ideals.In and amongst the energetic interactions that followed, the word ‘dada’ was chosen at random to undermine Western rationalist thinking. A playful anti-statement that pointed to their commitment to the absurd, Dada meant everything and nothing. In their hands, fine art lost its privileges, words lost their sense, and philosophy lost its head. Experimentation with chance and the irrational offered a transformation of the human spirit and an antidote to cynicism.

– Hugo Ball, 1916

In Zürich, we had no interest in the abattoirs of the World War…while the thunder of artillery rumbled away in the distance, we were putting together collages, reciting, writing verse, and singing with all our hearts. We were looking for an elementary type of art that we thought would save mankind from the raging madness of those times. We aspired to a new order that could re-establish the balance between heaven and hell. This art quickly became the object of general reprobation. It was hardly surprising that the ‘bandits’ could not understand us. Their puerile obsession with authoritarianism demands that even art should serve to stupefy mankind.

– Hans Arp, 1948

I know excellent people who have the name Dada. Mr. Jean Dada; Mr. Gaston Dada; Picabia’s dog is called Zizi de Dada… Dada belongs to everybody. Like the idea of God or of the tooth-brush. There are people who are very dada; there are dadas everywhere all over and in every individual. Like God and the tooth-brush (an excellent invention, by the way).With a violent war raging in the near distance, they cut, crafted, sang and danced their nonsensical proclamations, proving with each ‘wrong’ step they took that the humiliations of their age ‘had not succeeded in winning their respect’.

– Tristan Tzara, 1921

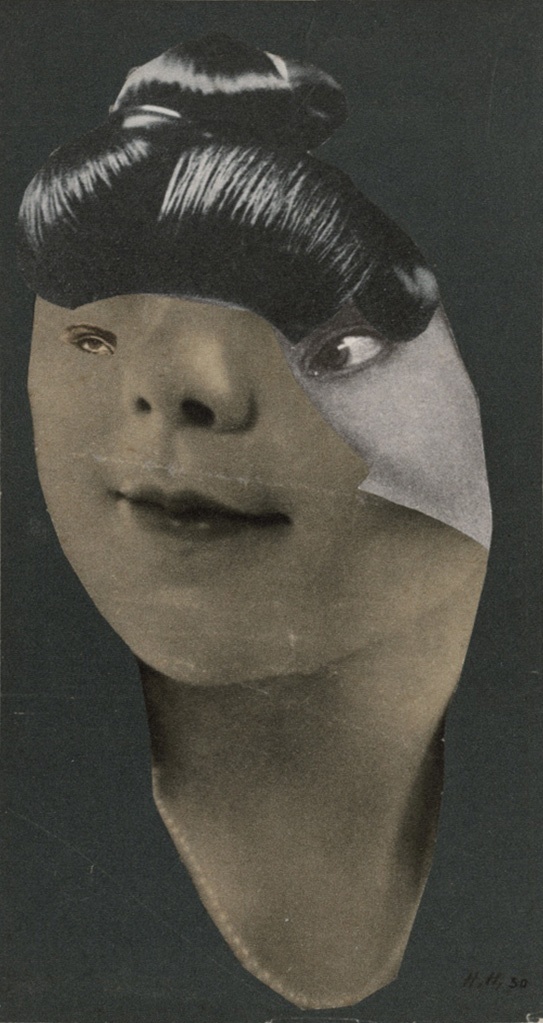

Disillusioned with the consequences of Western ideals like ‘reason’ and ‘civilisation’, the Zurich Dadaists embraced processes and strategies of intuition. They desired to achieve a ‘total’ experience akin to a spiritual transformation that would overcome the concerns of individual ego. This motivated them to look beyond the conservative norms of modern Europe. The traditions and practices of non-Western cultures, particularly those of Africa, offered an alternative that found hybrid form in their objects and performances.

From a post-colonial viewpoint, the adoption of non-Western cultural motifs by Western art is always treated with suspicion. In contrast to other practices of the time, where African imagery was ‘borrowed’ as an exotic curiosity, the Dadaists seemed to appreciate the transformative intentions of ritual practices in both a personal and collective sense.

Tzara is wiggling his behind like the belly of an Oriental dancer. Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping. Madame Hennings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits. Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop on the great drum, with Ball accompanying him on the piano, pale as a chalky ghost.‘Total pandemonium’ is how Hans Arp described a typical evening at the Cabaret Voltaire. Through rhythm and dance, they explored alternatives to verbal communication. Hugo Ball, costumed in cardboard shapes, delivered his absurdist poems in a trance-inducing drone, in counterpoint to Richard Huelsenbeck’s energetic drumming. Fashioned from everyday materials, costumes, masks and puppets were danced to life by Sophie Taeuber, Emmy Hennings and the rest.

– Hans Arp, 1916

We were all there when Janco arrived with his masks, and everyone immediately put one on. Then something strange happened. Not only did the mask immediately call for a costume; it also demanded a quite definite, passionate gesture…they represent not human characters and passions, but…passions that are larger than life. The horror of our time, the paralysing background of events, is made visible.“Everything starts with dance,” said Raoul Hausmann, “movements come long before verbal expression or even music…it is from this point that creation begins: build for yourself the walls and limits of your universe.”

– Hugo Ball, 1916

When Richard Huelsenbeck performed his ‘First Dada Speech in Germany’ in Berlin, 1917, he planted a seed in fertile ground. As World War I drew to a close, the social excesses, militaristic nationalism, bureaucracy and corruption of the Weimar period were most conspicuous in Berlin, where Raoul Hausmann founded Club Dada.

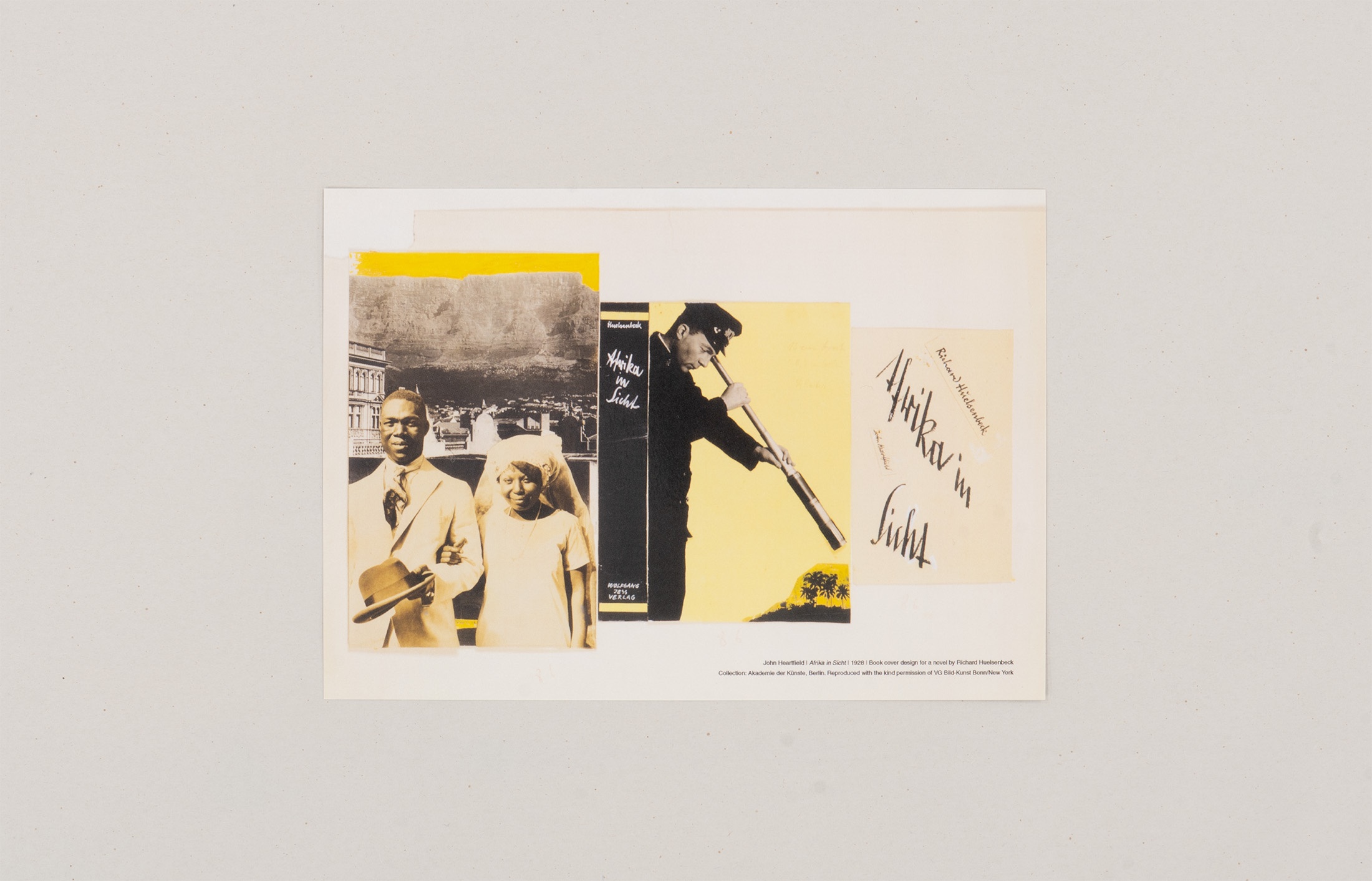

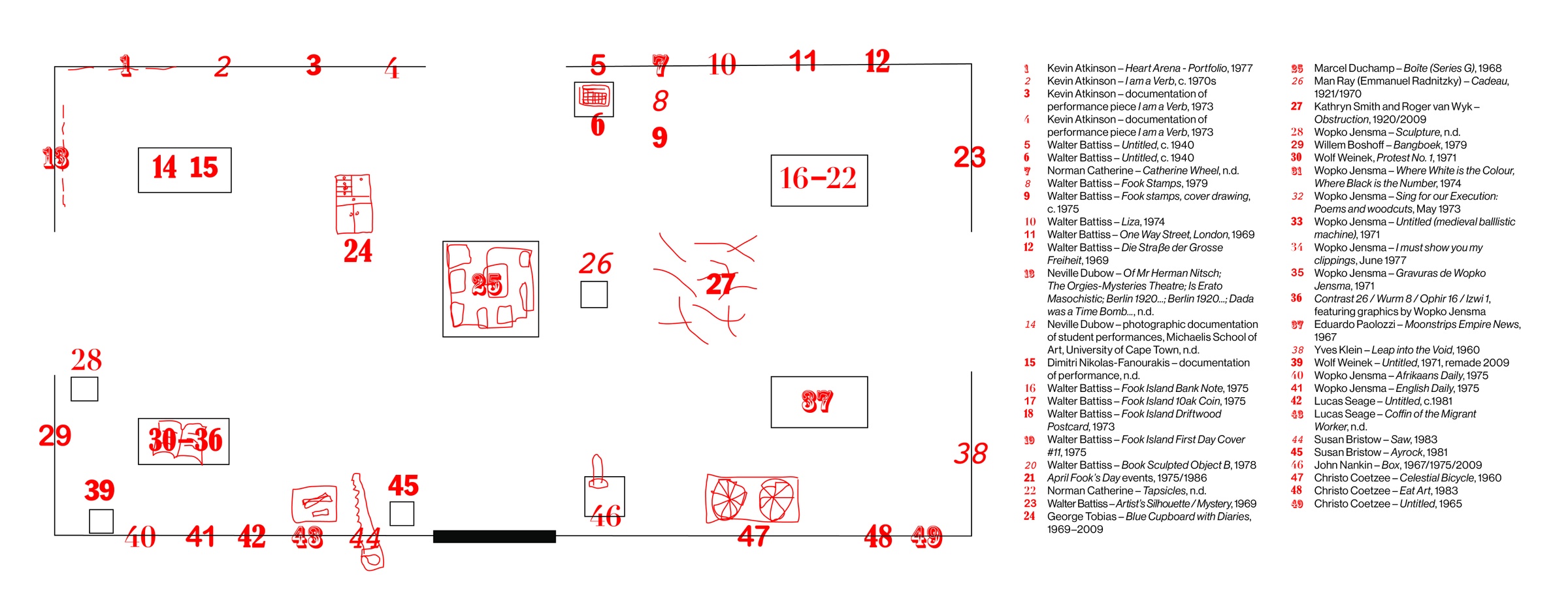

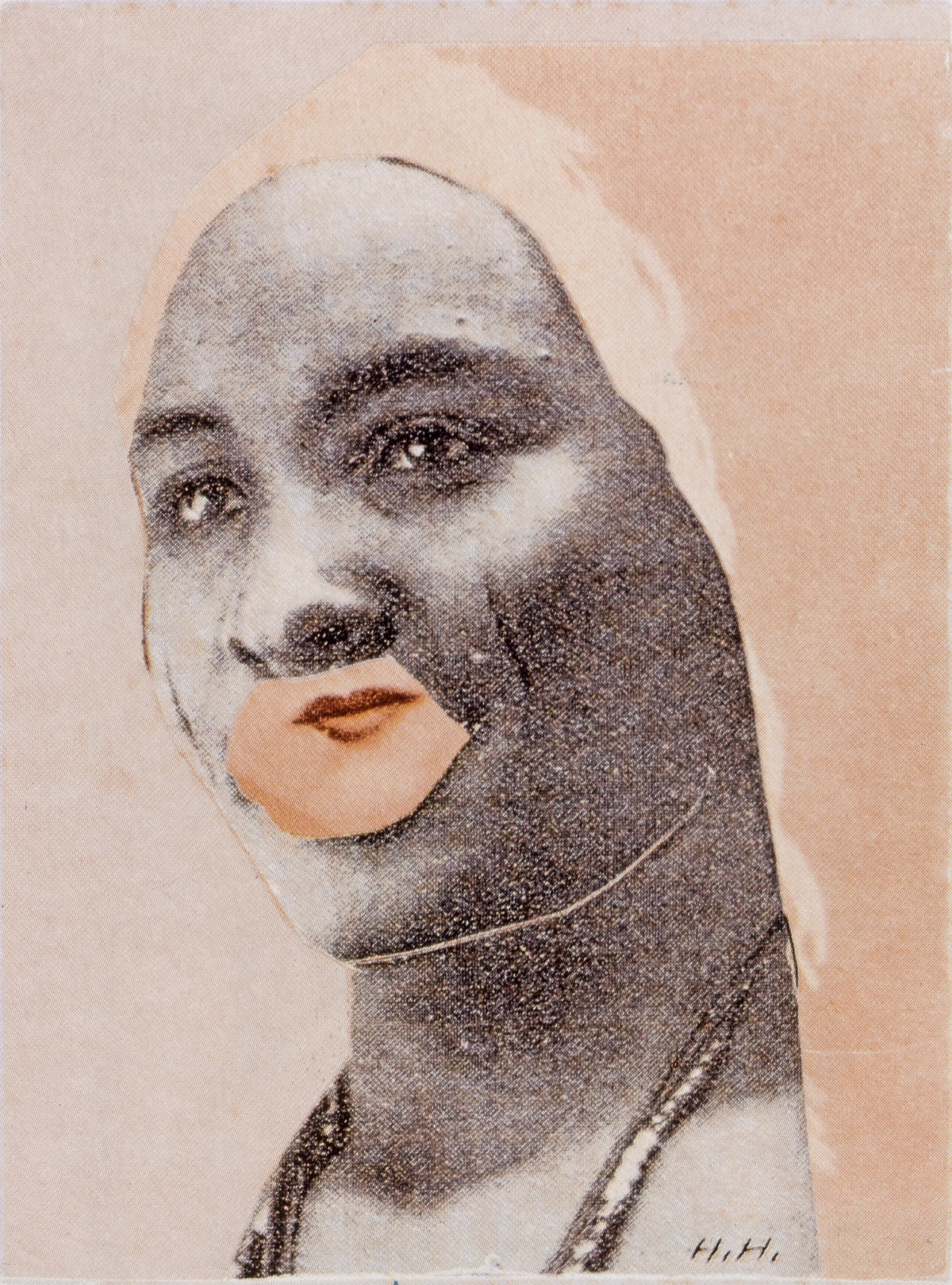

Dada’s rejection of bourgeois values was amplified by the Berlin Dadaists to accommodate their more explicit political agendas. Opposed to the aesthetic indulgences of Expressionism, George Grosz and Otto Dix called their scathing social criticism New Objectivity. Hausmann and Hannah Höch innovated various methods of collage and photomontage, the fragmentation of which echoed their view of a crumbling culture. John Heartfield employed similar tactics in his illustrations for the journals published by his brother Wieland Herzefelde, most of which were banned. Like the ruined bodies of the war cripples that characterised post-war society, Berlin Dada exhibited a dismembered and perverted version of the language of political propaganda.

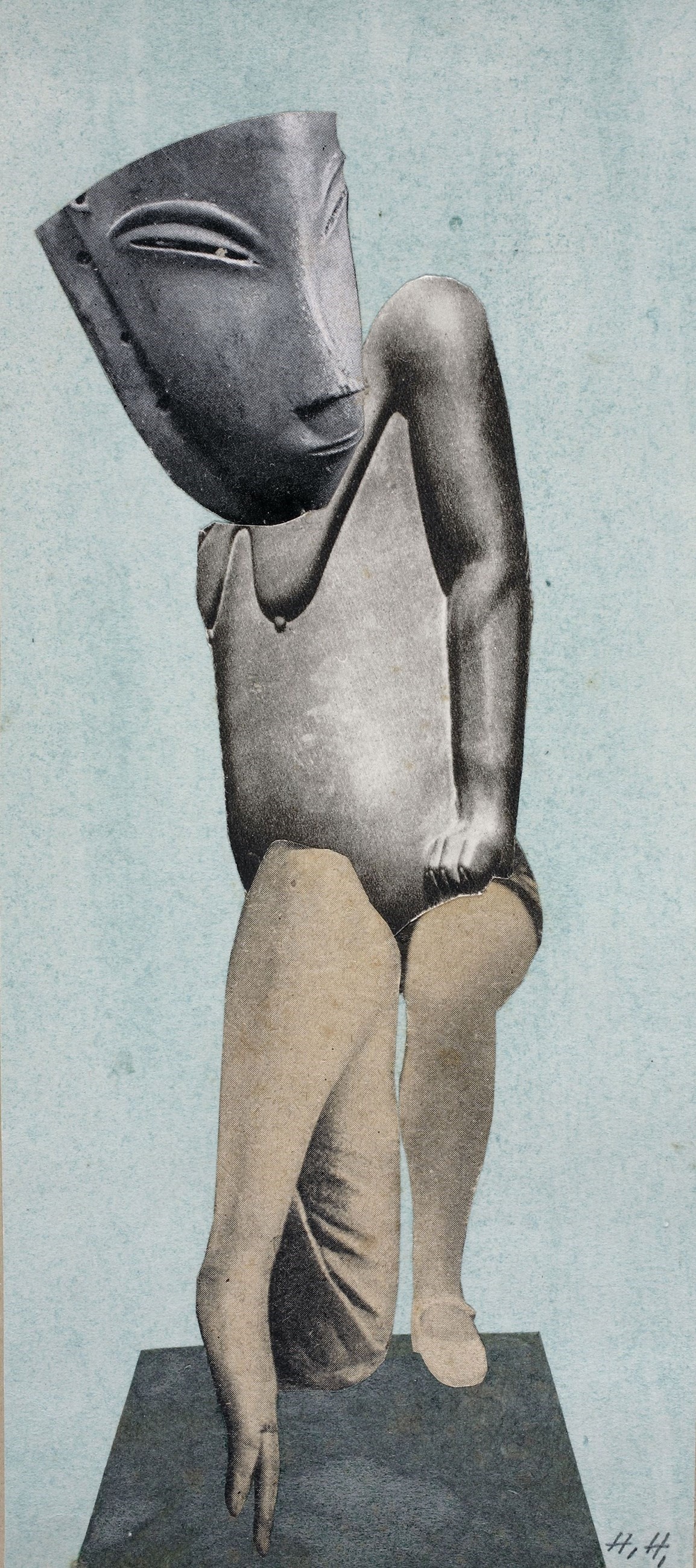

Dada montage aimed to give something that was utterly unreal the appearance of reality…our whole aim was to give an artistic interpretation of things from the world of machines and industry…we called this photomontage because it reflected our aversion to claiming to be artists. We regarded ourselves as engineers… Collage was born with the Dada movement, and it never ceased to hold me. I always believed that one should not only use it for tendentious work or applied art…it was a form of expression complete in itself and could culminate in purely aesthetic work.The Berlin Dadaists organised The First International Dada Fair (Dada-Messe) in June 1920. The exhibition included photomontages and collages by Höch and her partner Raoul Hausmann, as well as John Heartfield. Heartfield also presents two collaborative works. With George Grosz, he made The Enraged Conservative Bourgeois (1920), an assemblage figure that celebrates the mechanical Constructivist work of Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) while also pointing to the violence and ravaged bodies of the war.

– Hannah Höch, 1959/1968

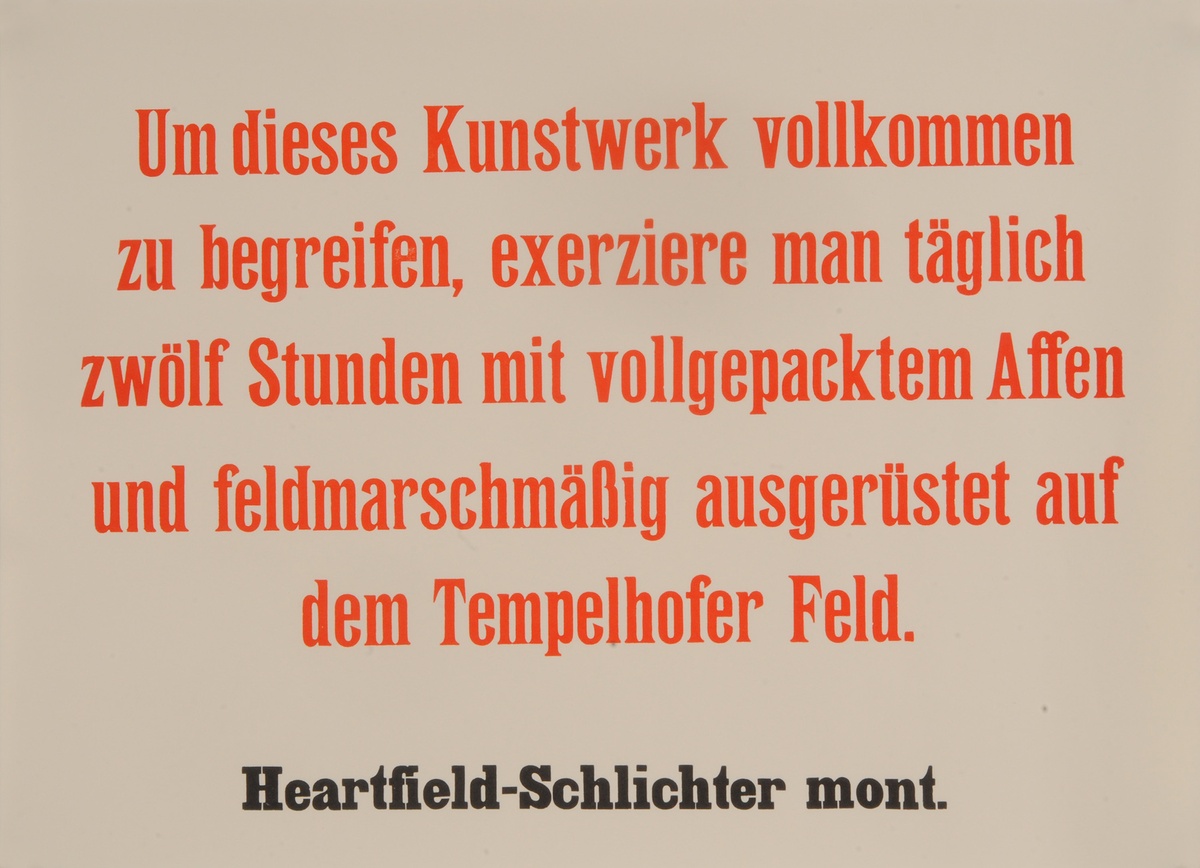

With Rudolph Schlichter, Heartfield constructs The Prussian Archangel (1920), a threatening figure suspended from the ceiling. Horrified by the various depictions of German authorities in compromising and unflattering positions, a colonel from the Reichswehr who visited the exhibition exclaimed, “You are all criminals and you ought to be shot!” The work was singled out as particularly offensive and the organisers of the exhibition subsequently faced prosecution. The sentence received was lenient, partly because the accused humbled themselves in their defence, promoting the socialist literary critic Kurt Tucholsky to comment that “the trial dilutes blood to lemonade. If Grosz didn’t mean it like that, we did.“

Despite the restrictions and international hostilities imposed by World War I, Dada was a nomadic movement, particularly evident in the widespread origins of its numerous journals. Dada’s intellectual legacy is directly linked to travel, either voluntary or enforced through exile.

The war drove both Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp from Paris to New York in 1915. They formed a pre-Dada group of like-minded artists and collectors, including boxer-poet Arthur Cravan, photographer Man Ray and painter Joseph Stella. Picabia would go on to meet Tristan Tzara in Zürich in 1919.

In 1917, the year after the Cabaret Voltaire was established in Zürich, Marcel Duchamp entered a porcelain urinal into the Independent Artists’ exhibition in New York under the assumed name of Richard Mutt. Being a member of the jury himself, Duchamp’s gesture was to test the limits of this so-called ‘independence’. The rejection of the work was documented in an issue of the New York Dada journal, The Blind Man. It was a turning point in the history of modern art: art was now a matter of declaration rather than discrimination. Anything could be art if it was declared so.

In 1920, Tzara travelled from Zürich to Paris at the invitation of writer André Breton. The Paris Dada Festival, organised shortly after his arrival, preceded the First International Dada Fair in Berlin by a month.

Eventually, this growing network included affiliated individuals in Hannover, Cologne, Barcelona and even Japan.

While the Berliners continued with their political agitation, Paris Dada developed a more aesthetic, inward focus that would eventually drive a major rift between the Dadaists and followers of Breton. By 1923, Paris Dada had disintegrated and was largely replaced by Surrealism.

(Source: Exhibition panel)

☞ Six Degrees of Separation

One has indeed to come to the end of the world, and for me at least to Africa, to find the most ancient, the most archaic things and also – surprisingly though it may seem – the most up-to-date, the most extraordinary things which were dreamt of forty or thirty years ago and are now becoming a reality on this soil of Africa… [T]his new world, which is in a state of ferment…is clearly going to be the world of the future.Neo-Dada (1958–62) is a contentious term used to describe an eclectic range of work made in the US and Europe in the period between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

– Tristan Tzara, after visiting Zimbabwe and Mozambique, 1962

Individuals including Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, Niki de Sainte-Phalle, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Eduardo Paolozzi and Daniel Spoerri sought new methods of making art outside of the stifling conventions of abstract painting.

The formalist assemblages of Schwitters, the combined eroticism and esotericism of Duchamp, and Dada’s commitment to direct action came under renewed scrutiny in this fluid, experimental and intense period that pre-empted the sexual revolution.

Like Dada, their range of practices and strategies was so broad as to defy easy categorisation, associated with various groupings such as New Realism, Fluxus, the Situationist International and Happenings. These ideas would set the terms for Conceptual Art, Minimalism, performance art and feminist strategies in later art, both in South Africa and internationally.

I don’t remember the term ‘Neo-Dada’ being used by anybody. I mean, I’ve probably just forgotten or blocked it out, because I see it’s used over and over again. I must have known about it, and I probably reacted against it. Any artist would react against an attempt to take a label from the past and put it on what they’re doing.With the renewed interest in Dada in the 1960s, artists like Duchamp and Man Ray created authorised editions of iconic early works. Man Ray’s first readymade, Cadeau (1921/1970), an object complicated by its ‘adoption’ by Surrealism, was reproduced as an edition of 5000 in 1970.

– Claus Oldenburg in conversation with Susan Hapgood, 1993

Duchamp’s influence in modern and contemporary art is definitive and pervasive. The Johannesburg Art Gallery purchased a 1968 edition of his Boîte (Series G) in 1996. The work functions as a portable museum, containing detailed miniature reproductions of his works, including paintings, readymades and other conceptual pieces.

Along with the combined eroticism and esotericism of Duchamp, Neo-Dada provoked renewed scrutiny of the formalist assemblages of Kurt Schwitters and Dada’s commitment to direct action. Yves Klein’s iconic image Leap into the Void (1960) captures this for a new generation. Recalling Dada’s playful absurdity, this carefully orchestrated photomontage is also a humorous indictment of photography’s supposed ‘truthfulness’.

Christo Coetzee left South Africa in 1951 to study abroad. His experimentation with assemblage painting began as early as 1956 in London. His Celestial Bicycle (1958/1960) was made in Paris prior to the year he spent in Japan, where he was associated with the avant-garde Gutai group. Firmly situated within Neo-Dada trends of the time, he had a two-man show with Lucio Fontana (Paris, 1959) and was included on The Art of Assemblage (1961) at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, alongside Duchamp, Schwitters, Daniel Spoerri, and others.

Deep conservatism and censorial authorities dominated apartheid society of the 1960s and 1970s. For some artists, art was both a personal and ethical space in which experimentation and political resistance should co-exist.

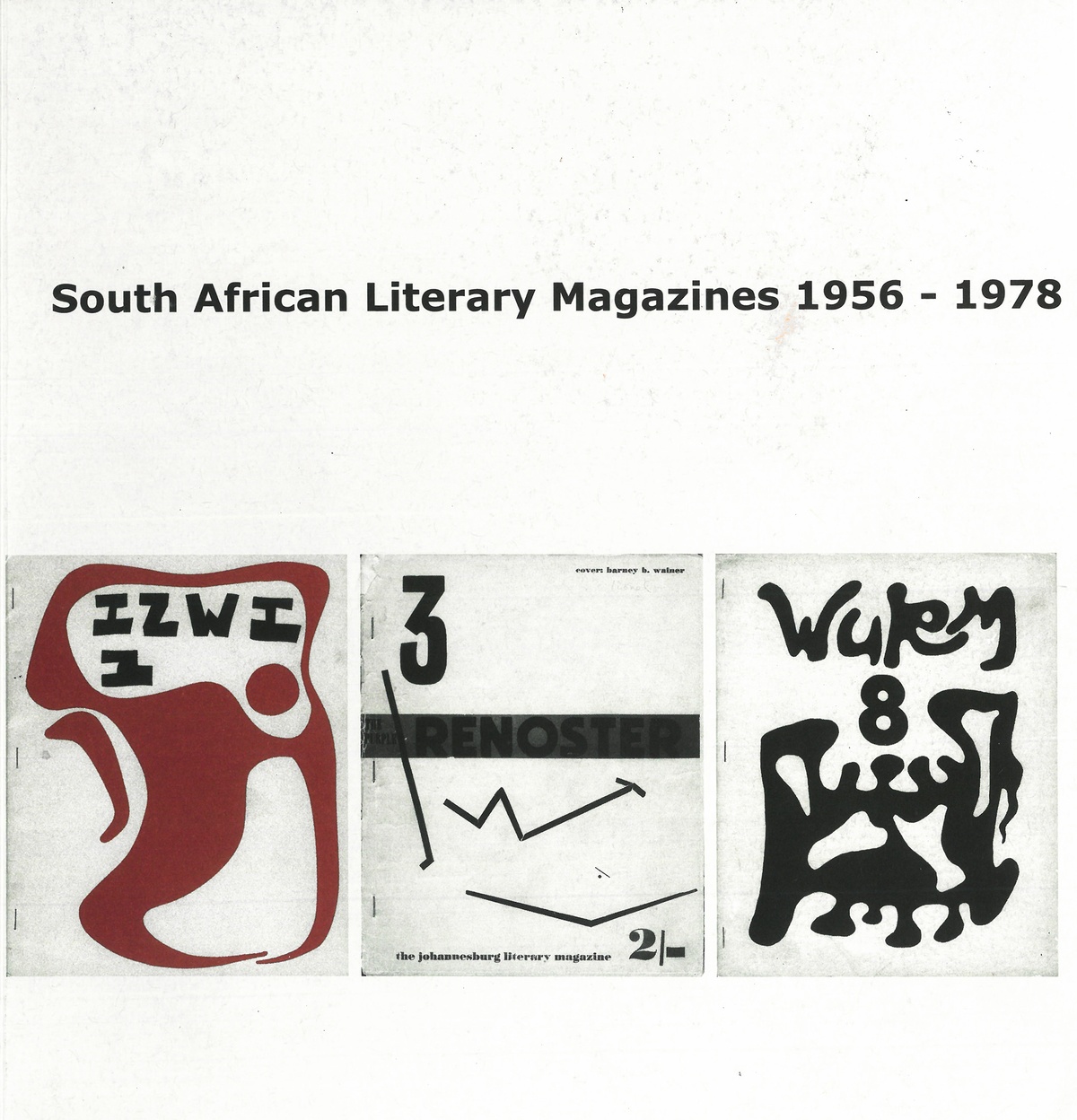

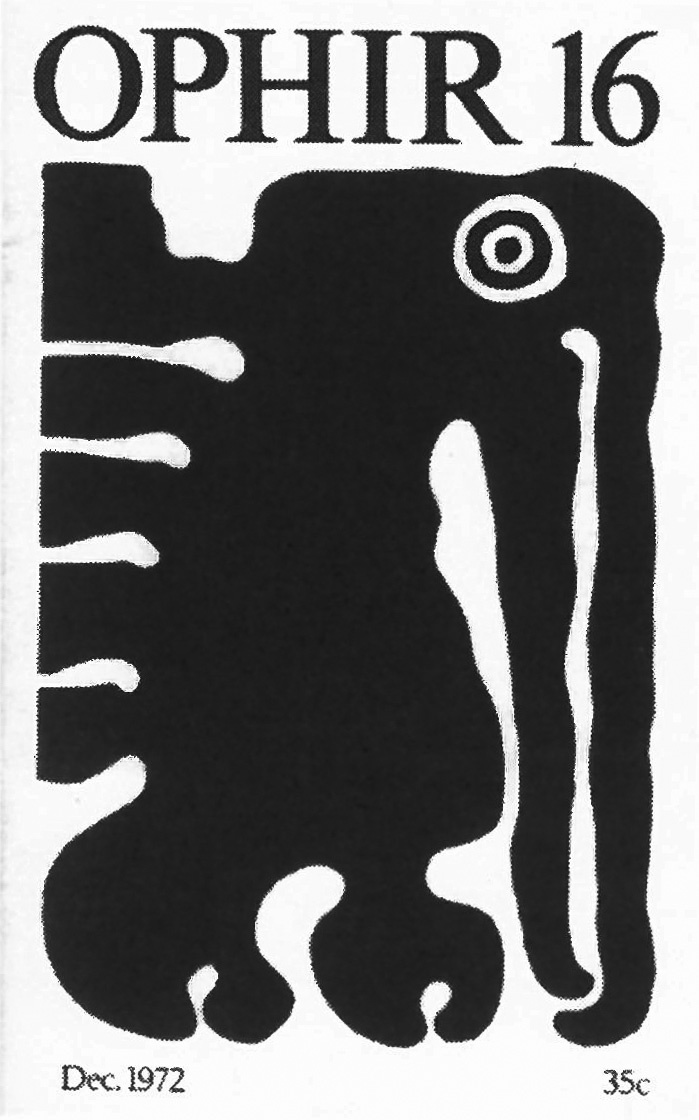

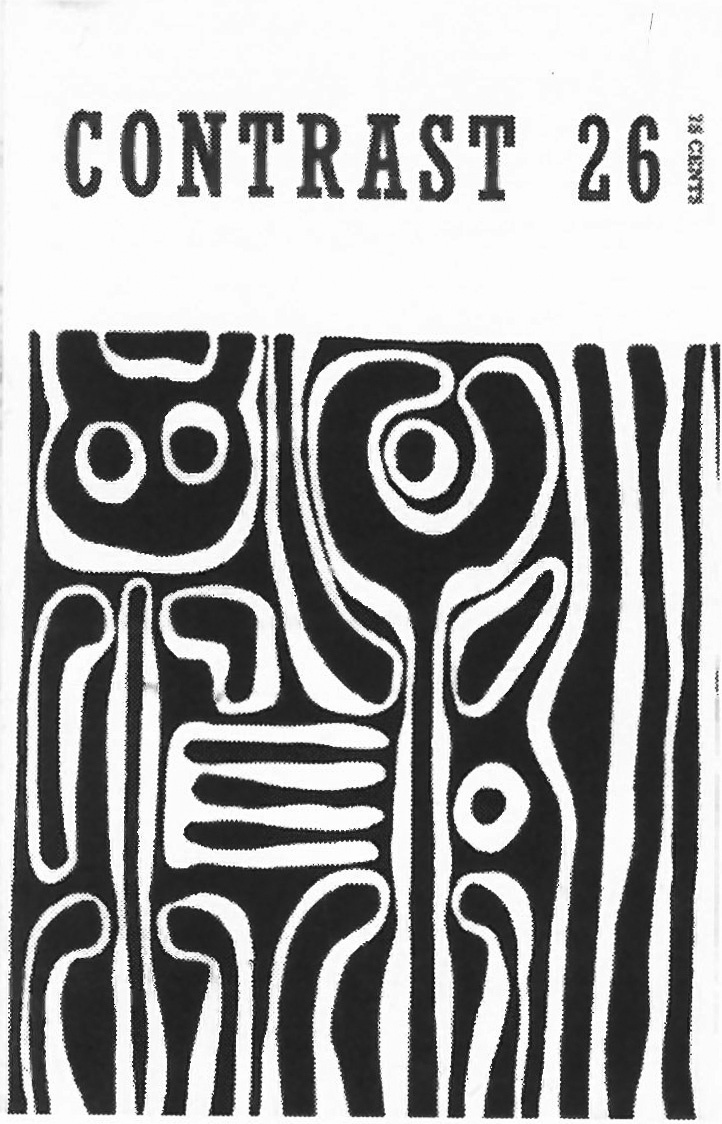

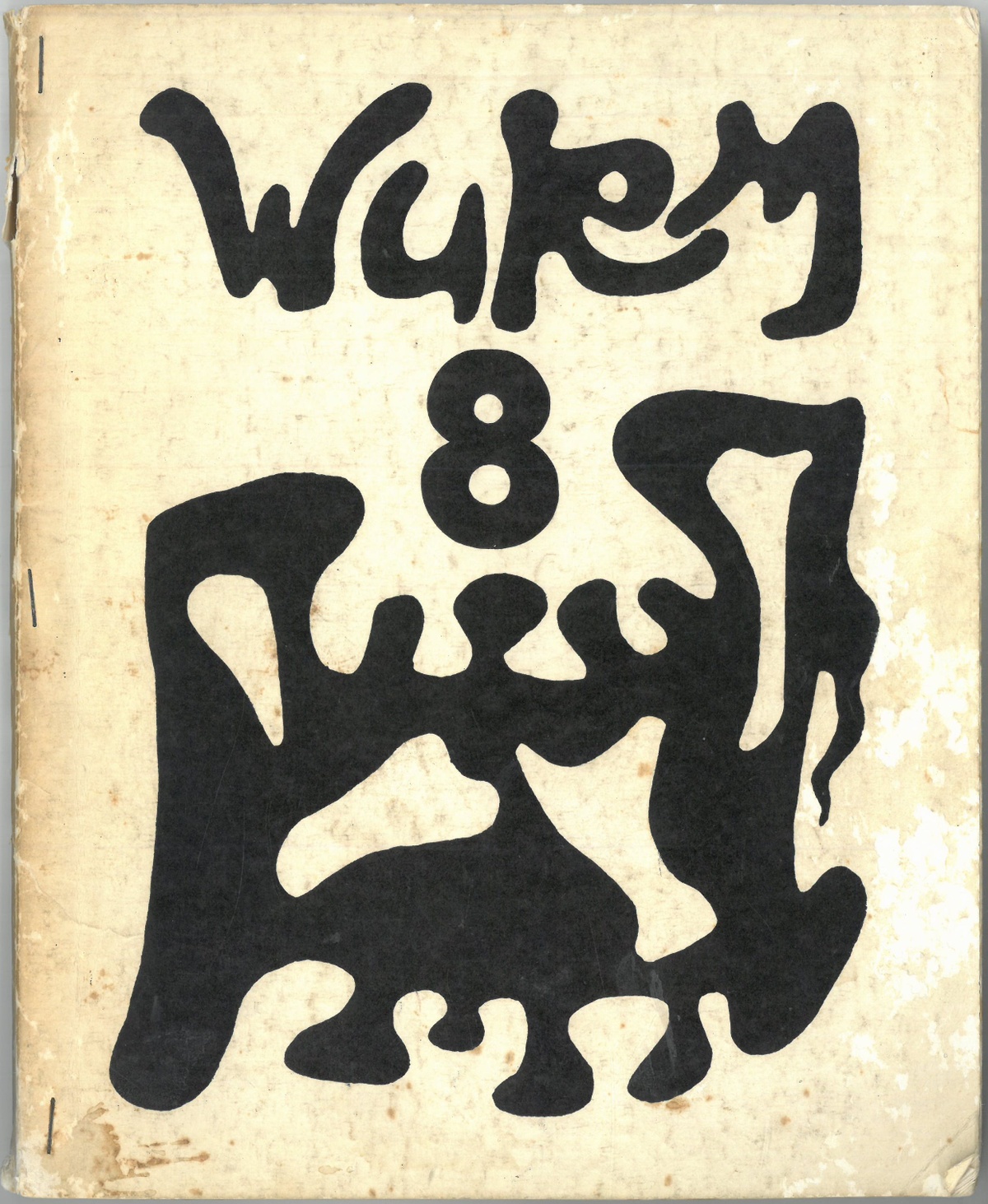

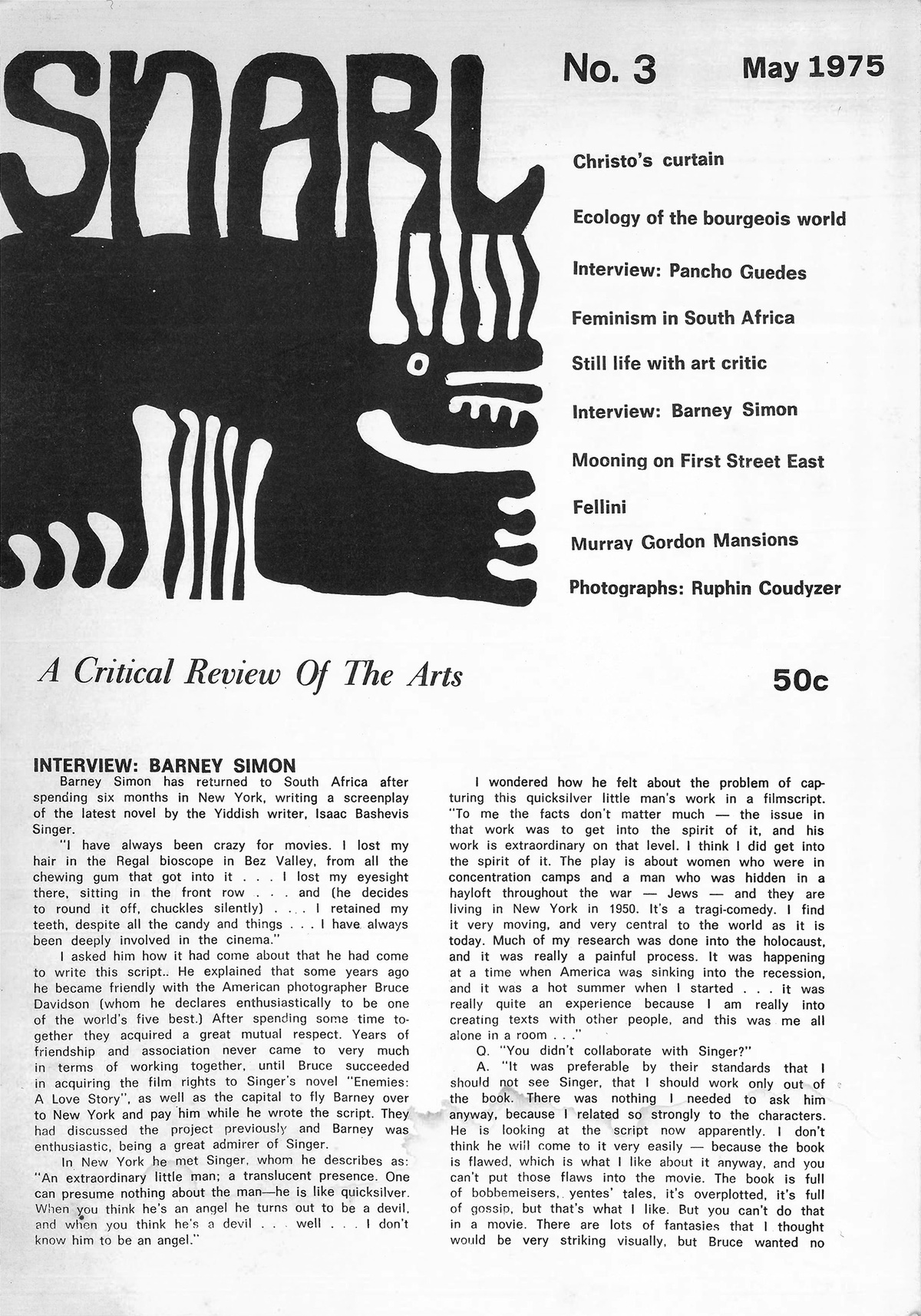

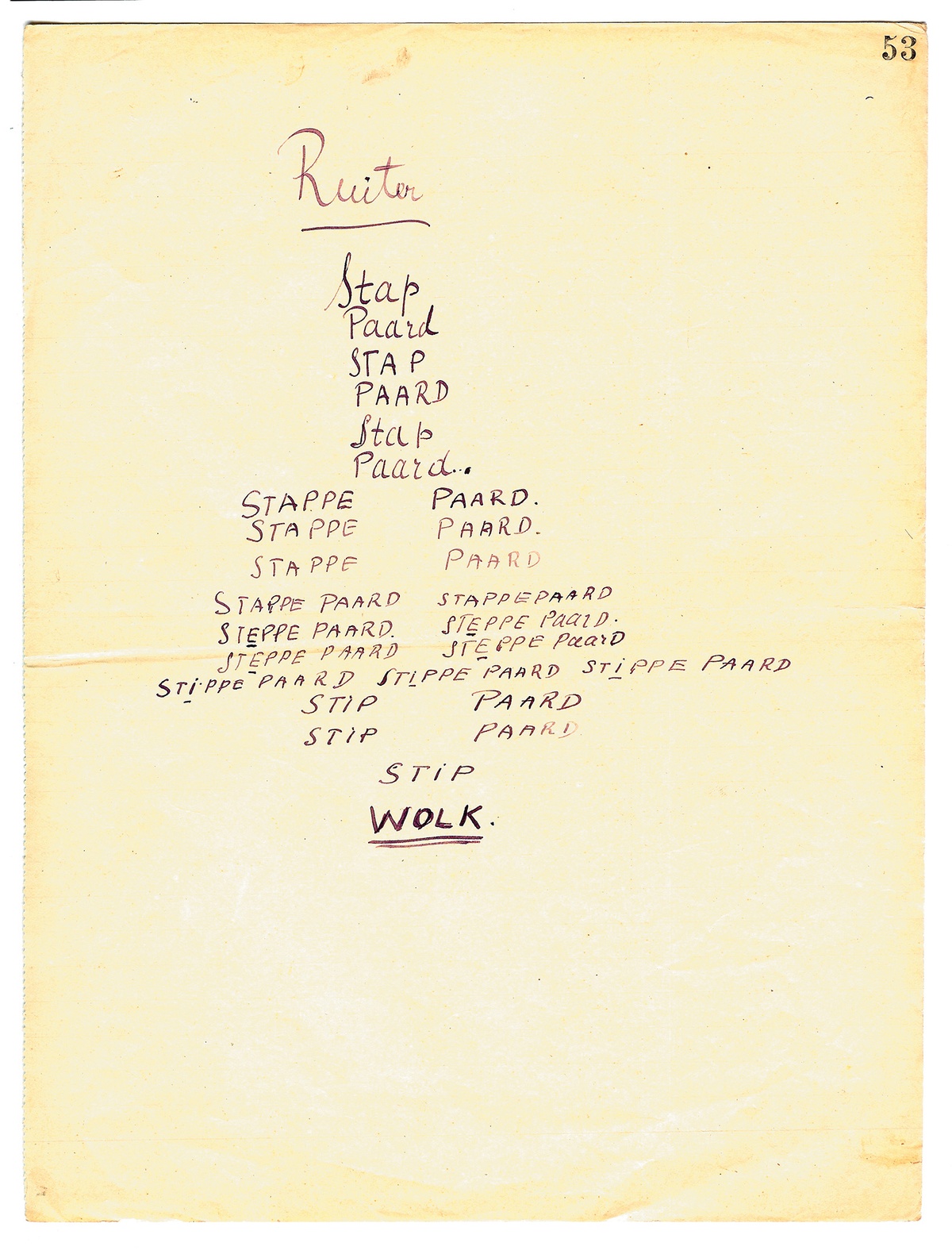

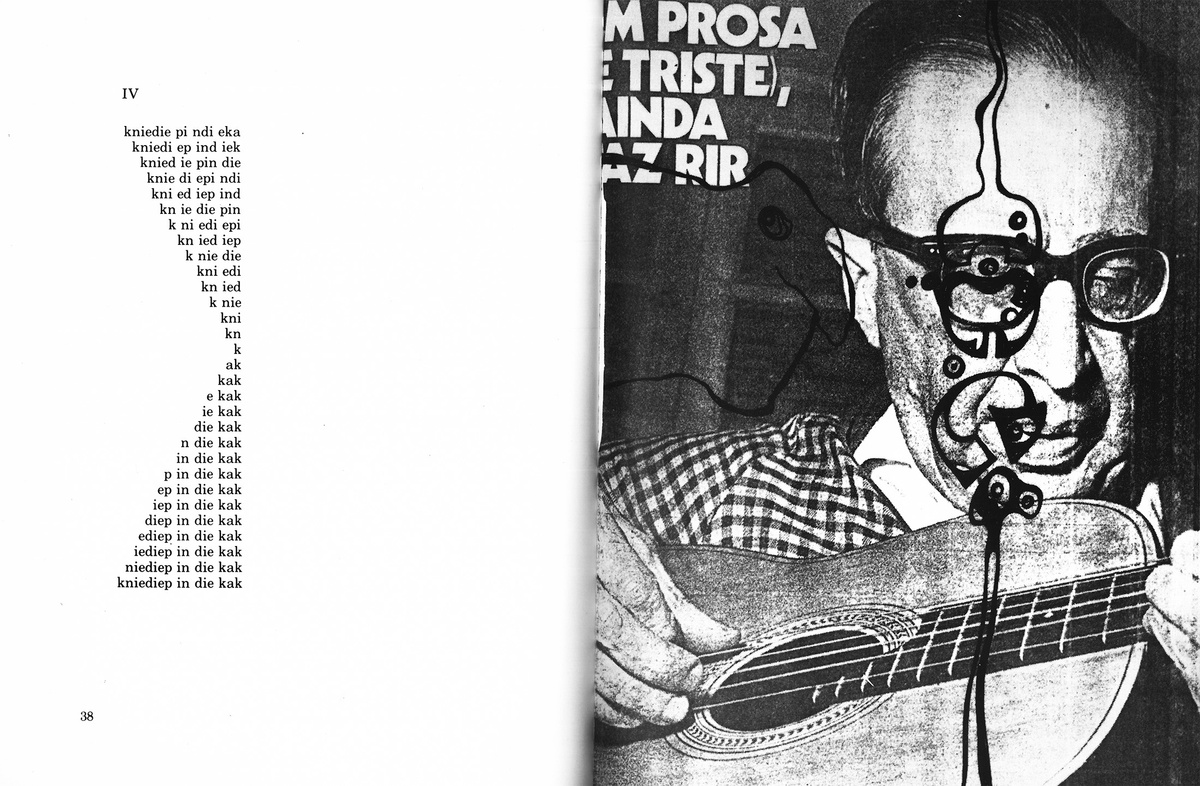

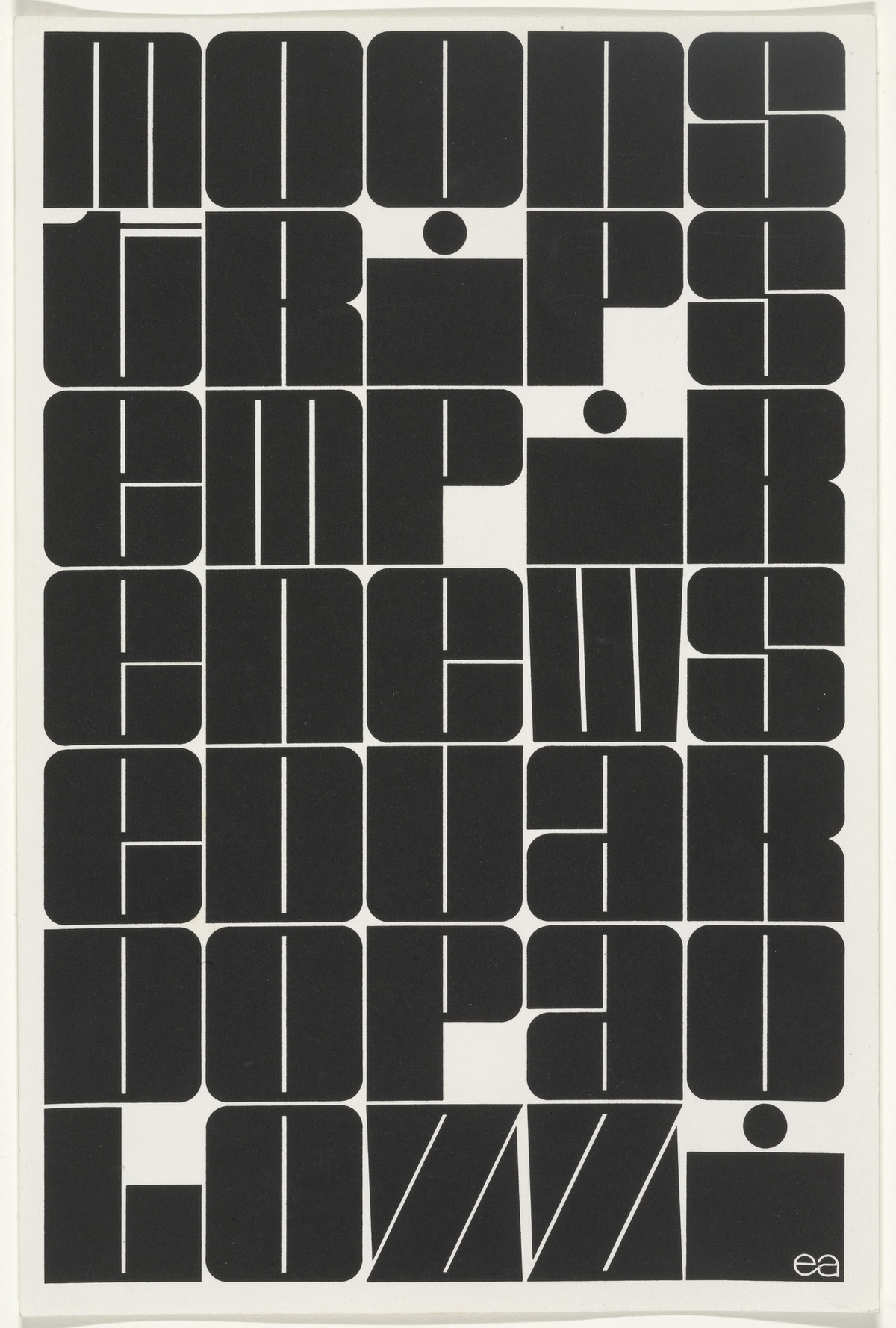

Independent literary journals demonstrated strong links between politically conscious artists and writers of the time. Wopko Jensma, a prolific printmaker and poet, had links with many of these journals, including Ophir, Contrast, Wurm, and Snarl. Jensma’s concrete poetry recalls the work of Dadaist Theo van Doesburg, who published under the name of I.K. Bonset.

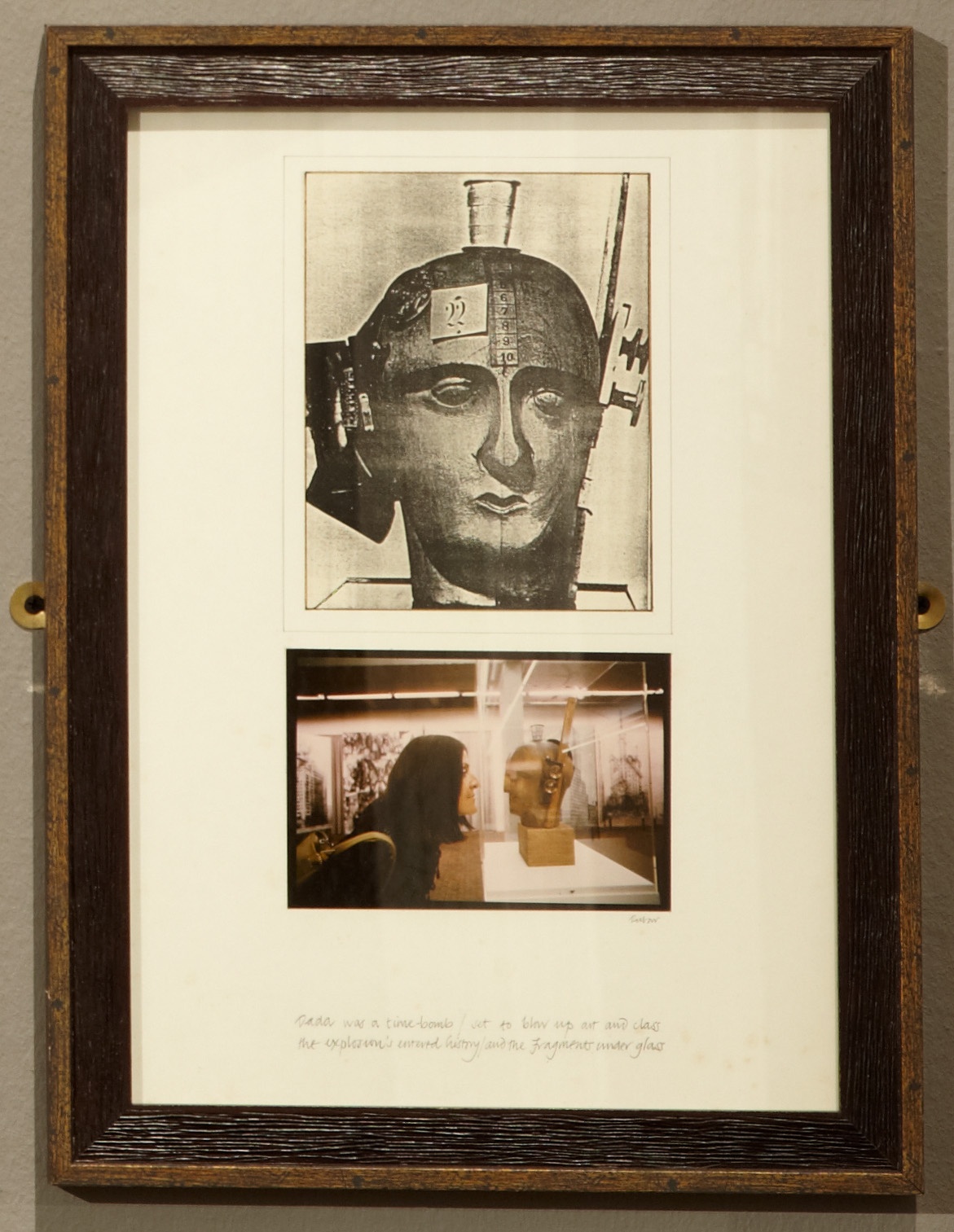

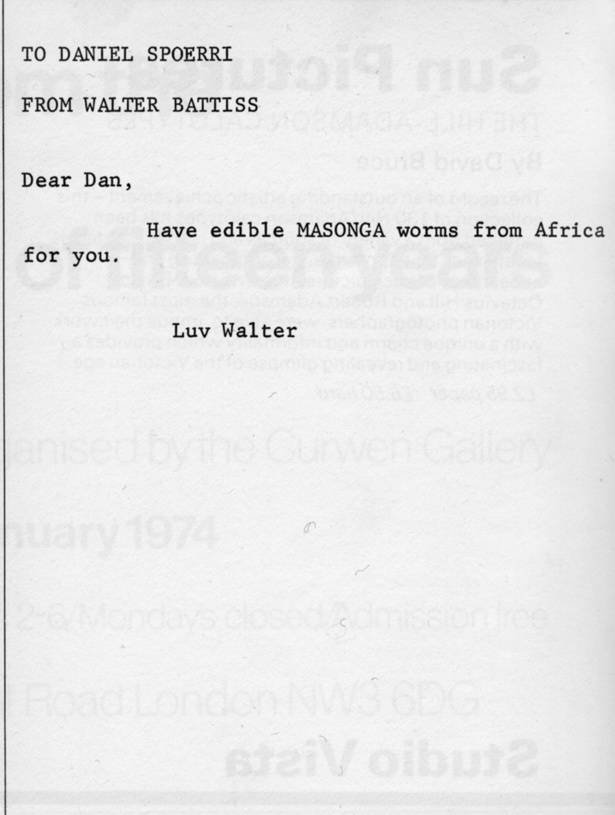

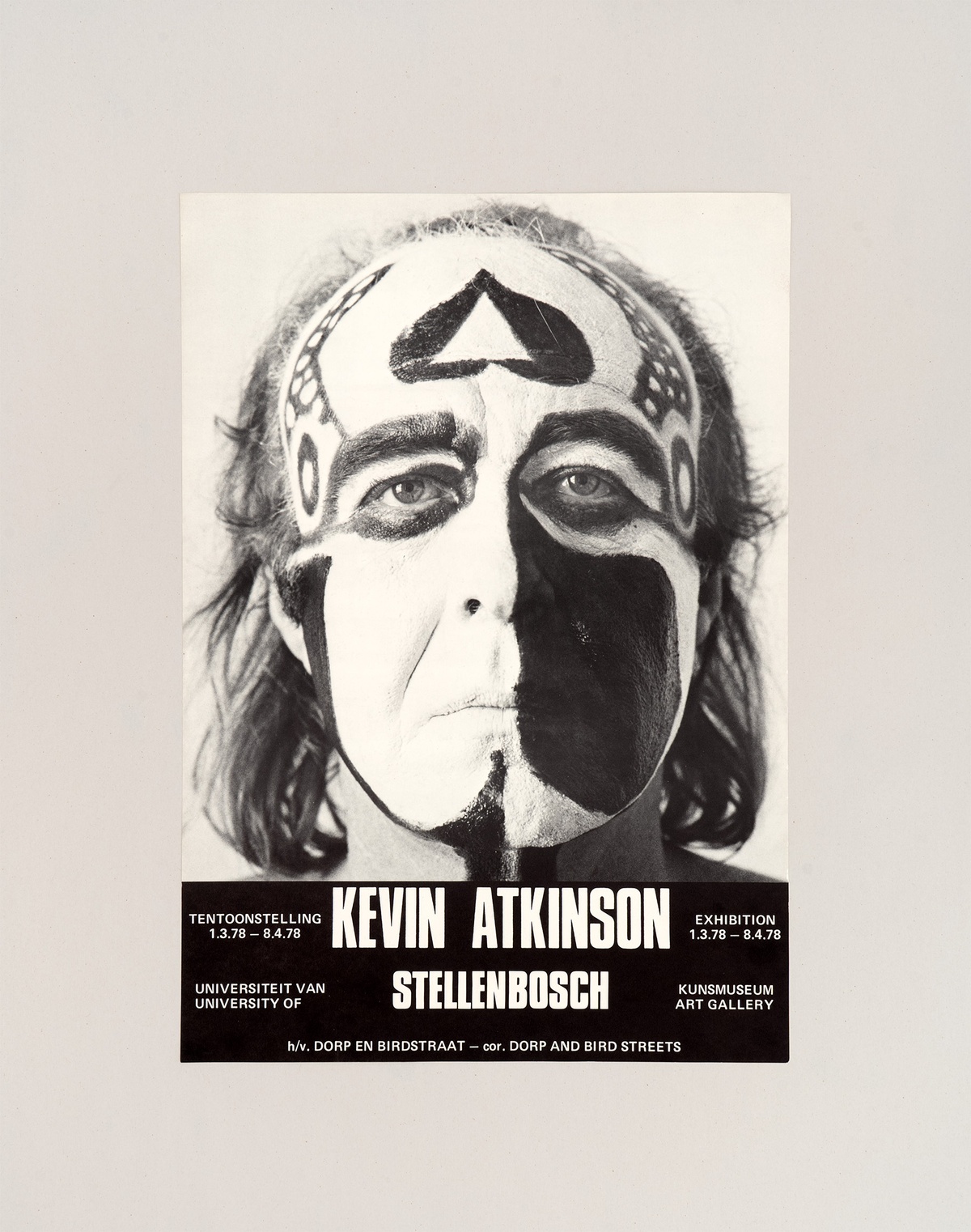

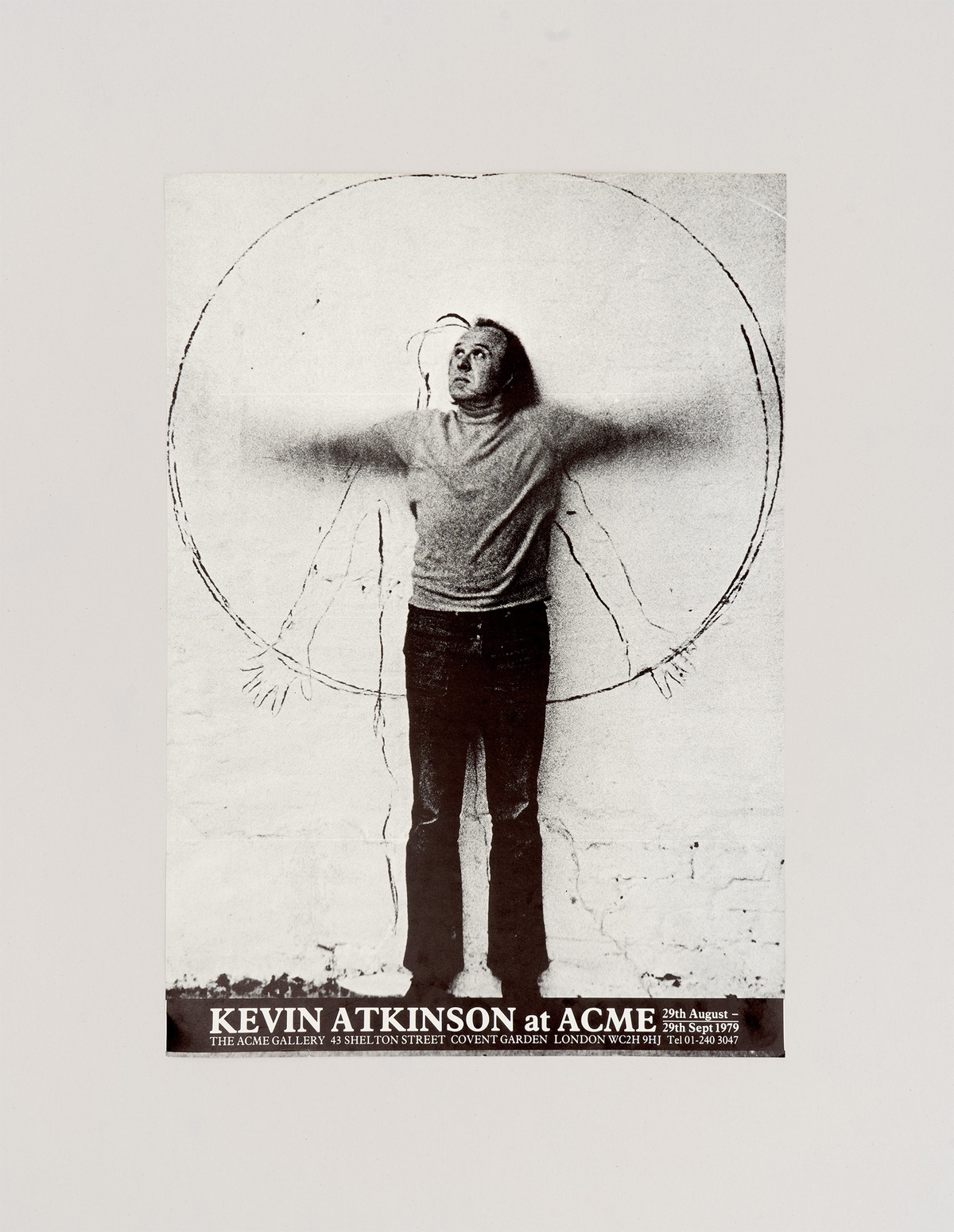

They had an exhibition of Dada art in London recently and they said that the punk people visiting the exhibition fitted in perfectly. How could one have known during Dada that punk and Dada would have come together so well?Exposure to the work of international artists and experimental practices took place mainly within urban art institutions (attended by predominantly privileged, white students) through influential teachers such as Kevin Atkinson, Walter Battiss, Willem Boshoff and Neville Dubow. Opportunities to travel to international exhibitions were invaluable sources of information on contemporary ideas, especially for Battiss, who maintained a friendly correspondence with Daniel Spoerri.

– Walter Battiss, 1979

Art’s relationship to revolutionary and totalitarian politics, focusing particularly on Dada and Weimar Germany, formed the core of Dubow’s syllabus, as these were subjects he felt appropriate for 1970s apartheid South Africa. For Willem Boshoff, it was imperative to introduce “a contemporary state of art” into his course. “If you were a doctor and prescribed medicine that was 100 years old, you would probably kill your patients,” he notes. Boshoff focused on the work of Eduardo Paolozzi as well as Jean Tinguely, whose language of ‘deformity and destruction’ he regarded as instructive.

Tinguely visited Pretoria in 1970 as a fan of the Grand Prix. He arranged to use the facilities at the Pretoria College for Advanced Technical Education (where Malcolm Payne was a student) to make a sculpture as a gift for Swiss friends who lived nearby. Risking his final art history exam, Payne made a 16mm film of Tinguely at work on the sculpture. This film makes its first public appearance on Dada South?.

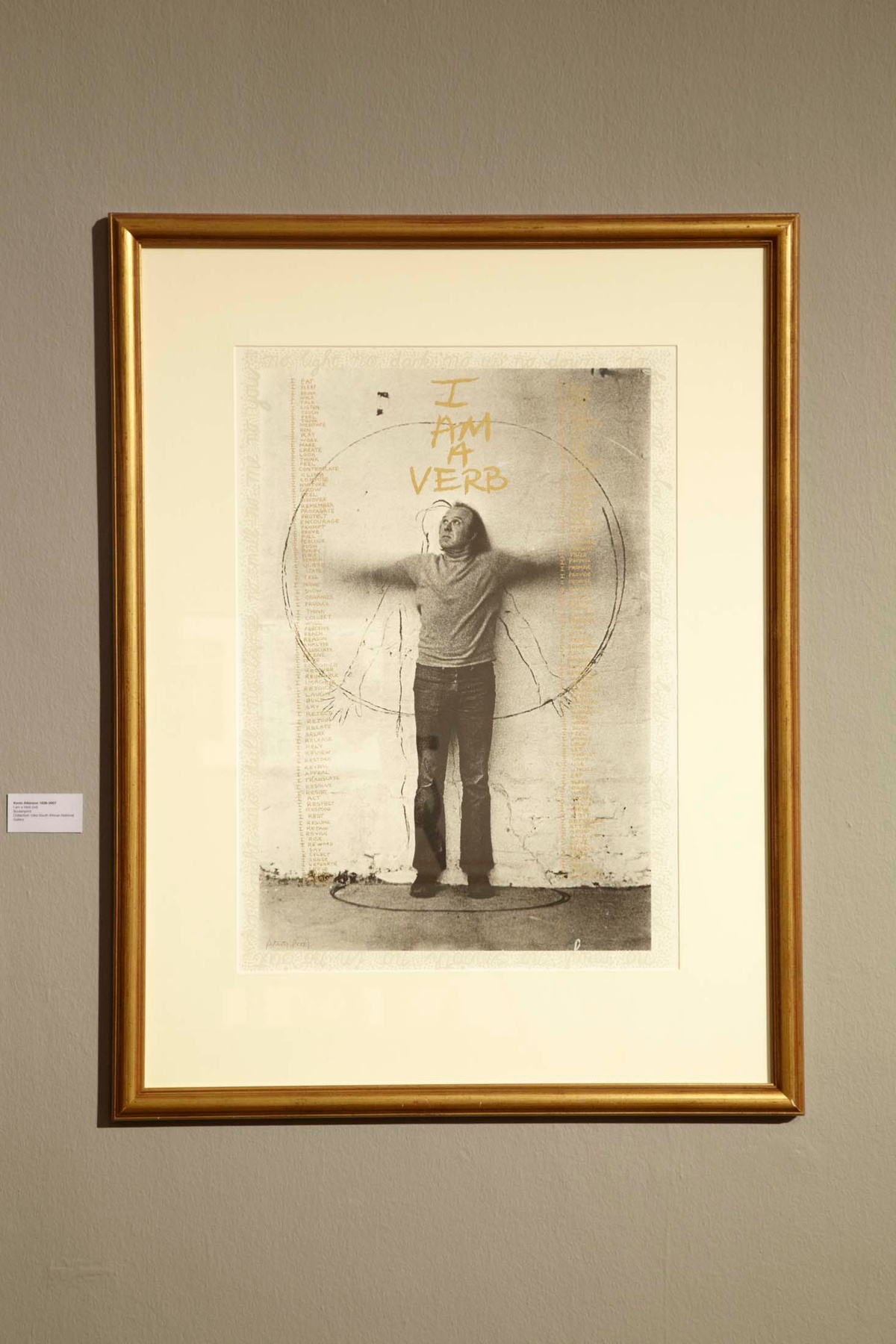

In Kevin Atkinson, an interest in ‘systems art’ informed a prolific career of painting, printmaking and experimental performance, where process becomes a means of spiritual self-realisation. Needing to disguise obvious political opposition for fear of censure, the imaginary Fook Island of Walter Battiss and Norman Catherine represents a poetic refuge for creative and personal freedom.

Out of this, two distinct trends emerged: an identification with Neo-Dada’s language of ‘deformity and destruction’ and formalist concerns informed by mysticism and spirituality that stood in opposition to Calvinism. Needing to disguise obvious political opposition for fear of censure, the imaginary Fook Island represents a poetic refuge for creative and personal freedom.

(Source: Exhibition panel)

☞ The Body of the Voice

The Constructivists living in Germany called a congress in October of 1922, in Weimar. Arriving there, to our great amazement we also found the Dadaists Hans Arp and Tristan Tzara. This caused a rebellion against the host (Theo) van Doesburg… A powerful personality, he quieted the storm and the guests were accepted to the dismay of the younger, purist members who slowly withdrew… At that time we did not realise that van Doesburg himself was both a Constructivist and Dadaist writing Dada poems under the pen name of I.K. Bonset.

– Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

A close relationship between Dada, Merz, Constructivism and De Stijl was inevitable given the frequent correspondence between artists associated with these groups, characterised by strong formalist concerns. Dadaists and Constructivists encountered the same hostility to change in society and shared creative processes such as photograms, film and collage.

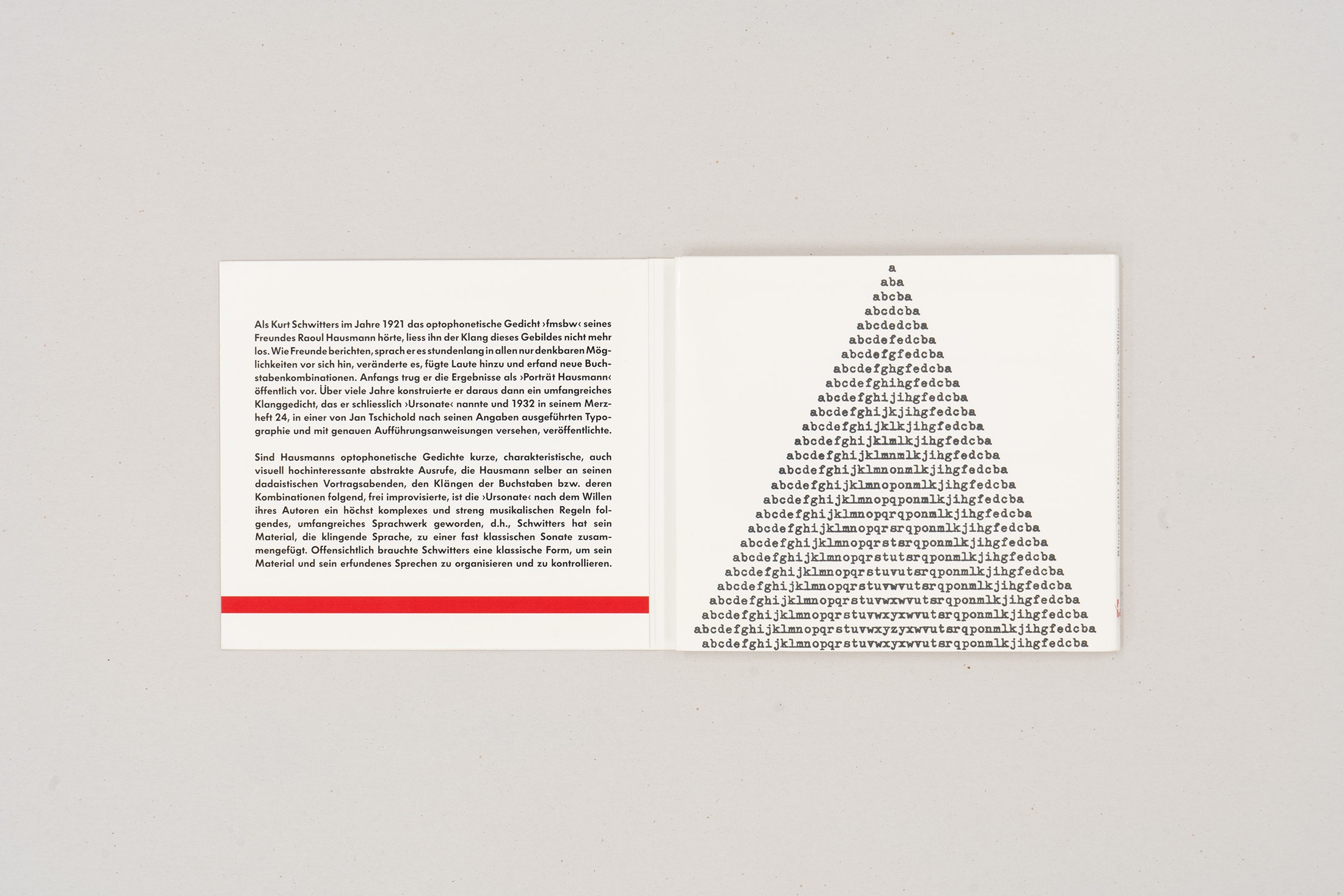

After Richard Huelsenbeck turned down Kurt Schwitters’ request to join the Berlin Club Dada (on the grounds that Schwitters was ‘bourgeois’), Schwitters created Merz, ‘a Dada of his own’. It functioned as a core philosophy and a prefix for the diverse range of works that he generated, including a journal.

Schwitters’ friendship with Theo van Doesburg, founder of De Stijl and editor of Dada Constructivist journal Mecano, generated innovations in the field of concrete visual poetry. It was after the Weimar Constructivist meeting in 1922 that Schwitters began work on his iconic Merzbau (1923) as a response to the functional imperatives of Bauhaus design.

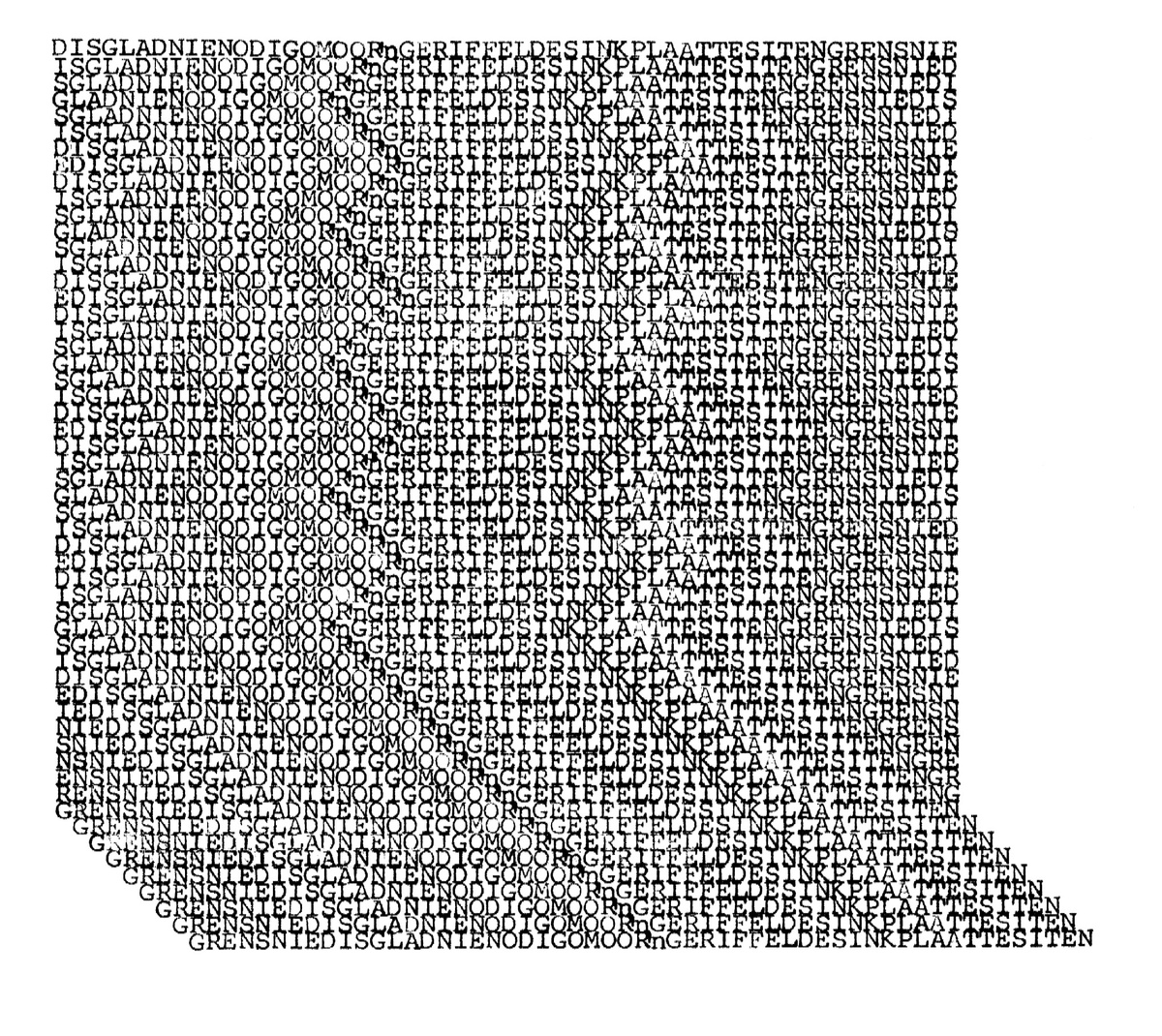

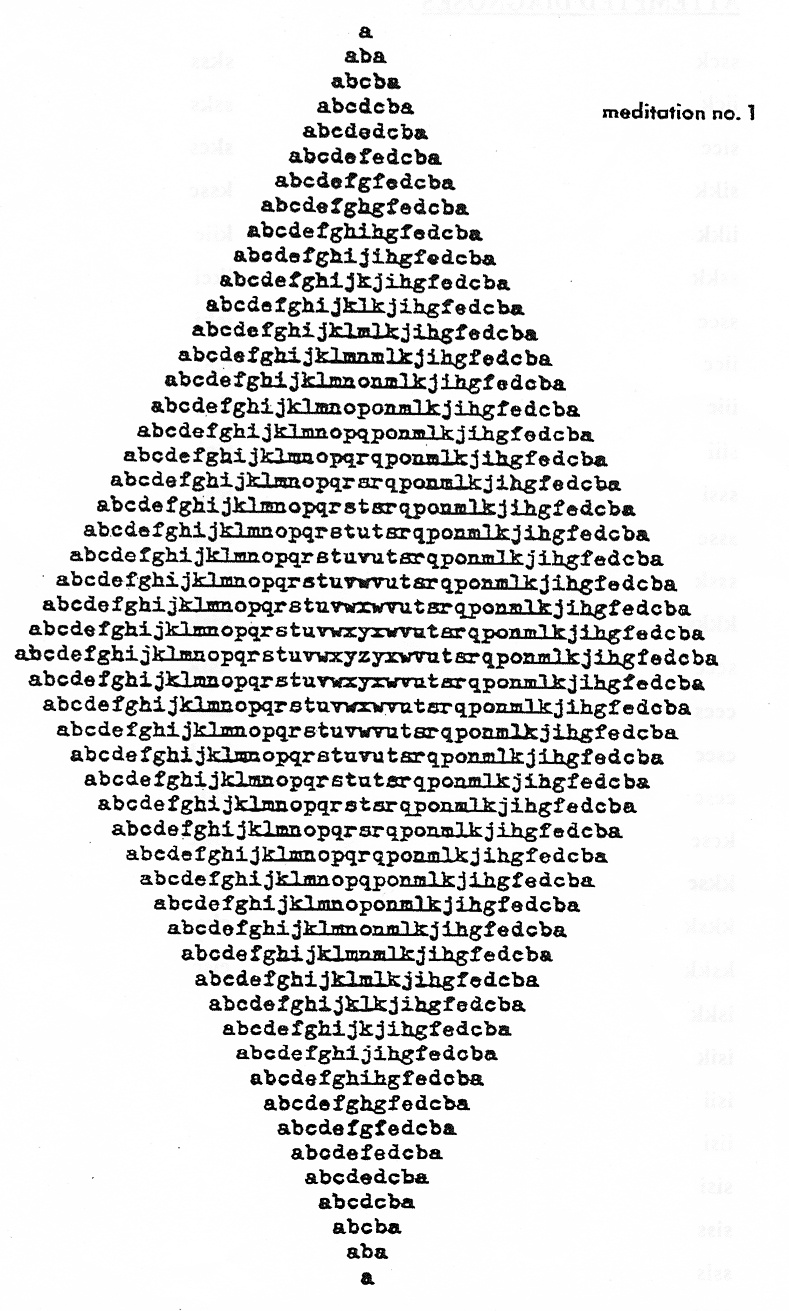

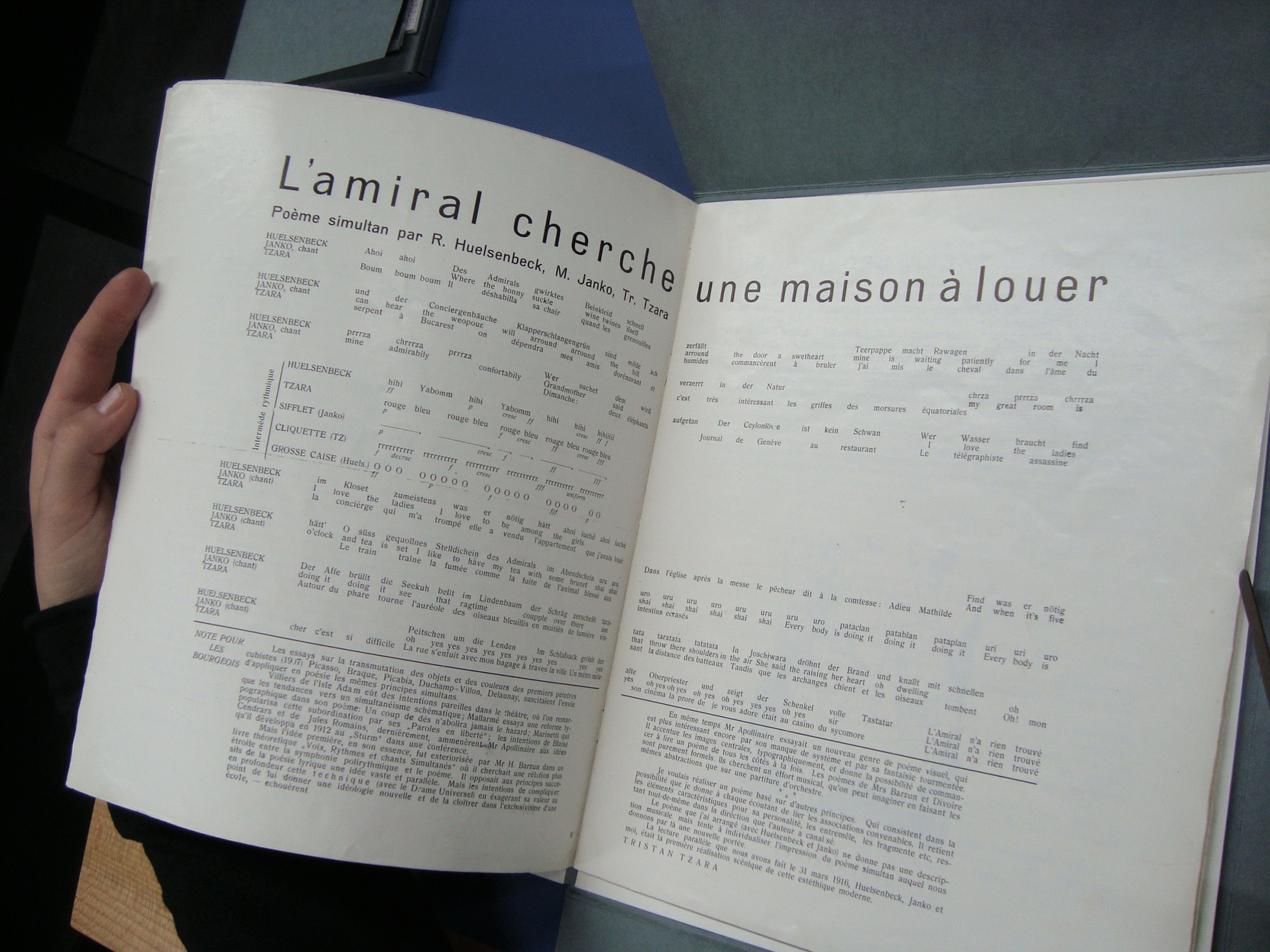

The role of language in society is fundamental and structural, expressing ideas about subjectivity and power. Dada experimentation with the written, printed and spoken word sought to undermine the more oppressive and exclusionary powers of language by ‘freeing’ it from conventional use and emphasising its visual forms.

Chance combinations of letters suggest sounds and rhythms rather than meaning. Raoul Hausmann described this as ‘optophonetics’ – an optical impression of a sound. Kurt Schwitters and Theo van Doesburg harnessed this strategy in their development of ‘concrete’ poetry, taken further by the Lettrists in the 1940s.

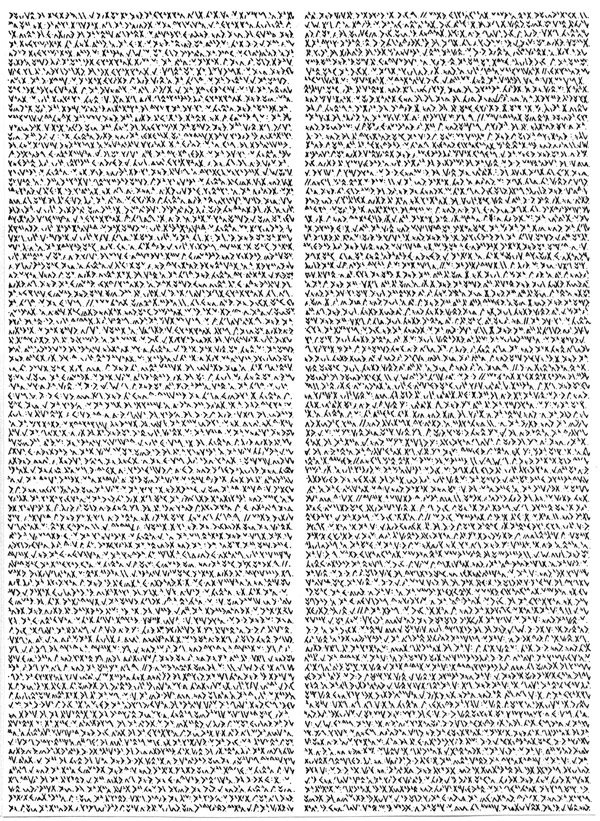

In concrete poetry, the visual form of the poem – its shape and typography – echoes the ideas it contains. This is the principle behind Willem Boshoff’s Kykafrikaans. Willem Boshoff’s Kykafrikaans (1976–1980) is greatly informed by optophonetics, a strategy also used by Wopko Jensma.

Candice Breitz interferes with the narrative flow of a novel by deleting words the way a censor would. The gaps she creates open up the possibility of another narrative ‘hidden’ within the main story, which emerges as a provocative impression made up of text fragments.

The concept of ‘performativity’ emphasises the ability of language to produce, rather than simply describe, an experience of reality. Performativity is an idea derived from linguistics and closely associated with theatre practice. Theorist Judith Butler has applied the concept to her thinking about the relationship between subjectivity and society, including gender development and politics.

In Julia Rosa Clark’s Modernist Posters (2007), she creates clear stylistic references to the design and typography of early modernist avant-garde design. She cuts verbal declarations and lyrics from pop songs and collages them together in a manner that finds visual form for the emotional register of each scenario.

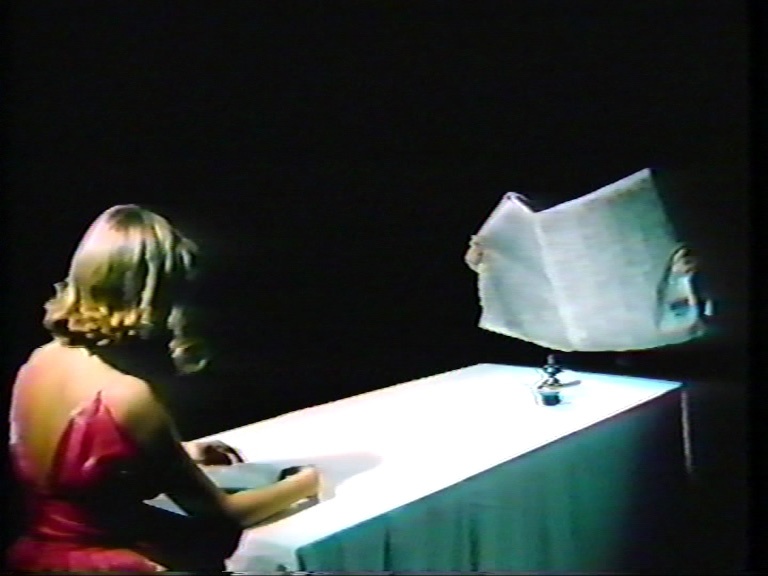

Interfering with the ‘sense’ of language creates new forms in the non-linear operations of digital media. Aesthetic experience is increasingly a matter of participation. In Nathaniel Stern’s Stuttering (2003), the work is activated by human presence. The piece ‘speaks back’ to you, depending on the gestures you make and where these gestures are situated in the projected field.

(Source: Exhibition panel)

There is no language any more. It has to be invented all over again.

– Hugo Ball, 1927

☞ South Africa 1980s–present

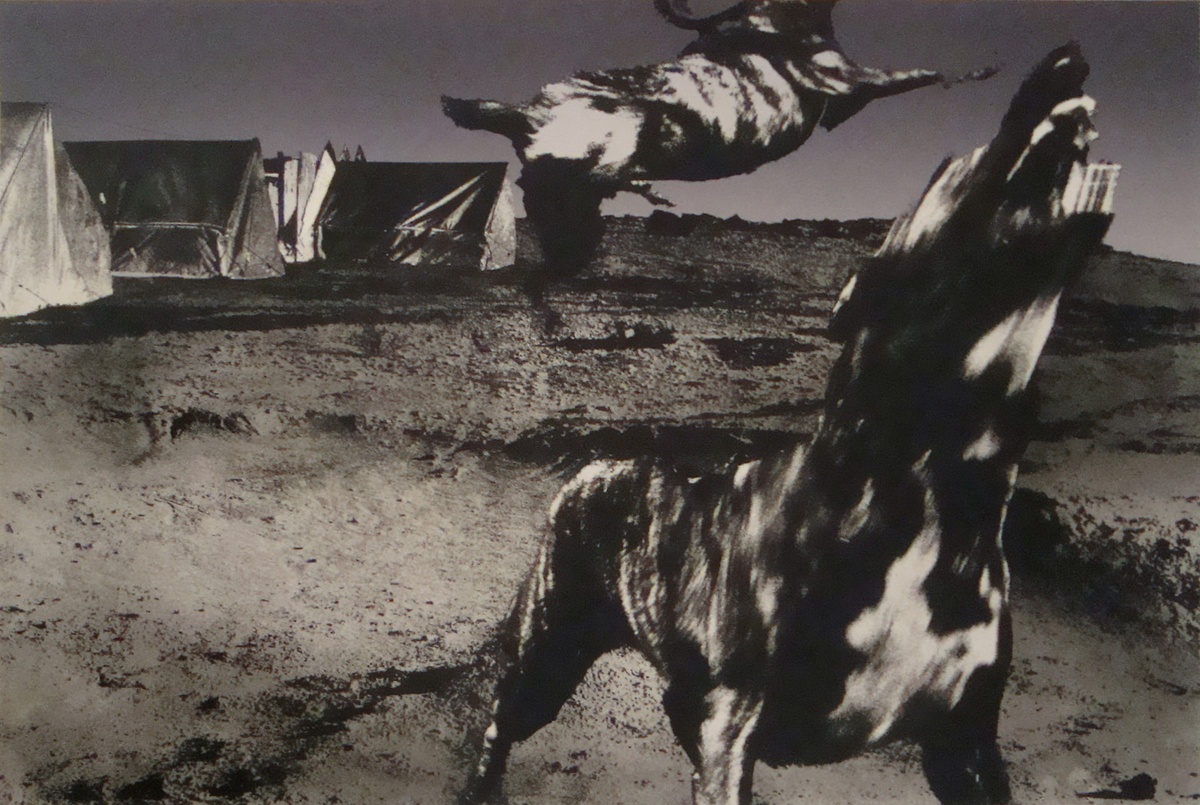

The 1980s in South Africa were characterised by despair, terror and anger. ‘Security’ forces attempted to quash increasingly aggressive political resistance. Some chose exile; for others, it was a matter of life or death. The fine balance that artists had to strike between freedom of expression and self-censorship became ever more treacherous. In the words of experimental Afrikaans band Koos, South Africa was ‘een honderd en een persent bang’ (101% scared).

The political thrust of Berlin Dada and New Objectivity was an important reference for South African artists who perceived the tragic history of the rise of Nazism in Weimar Germany repeating itself in South Africa. Some used the figure of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu the King (1896) as a metaphor for an absurd abuse of power.

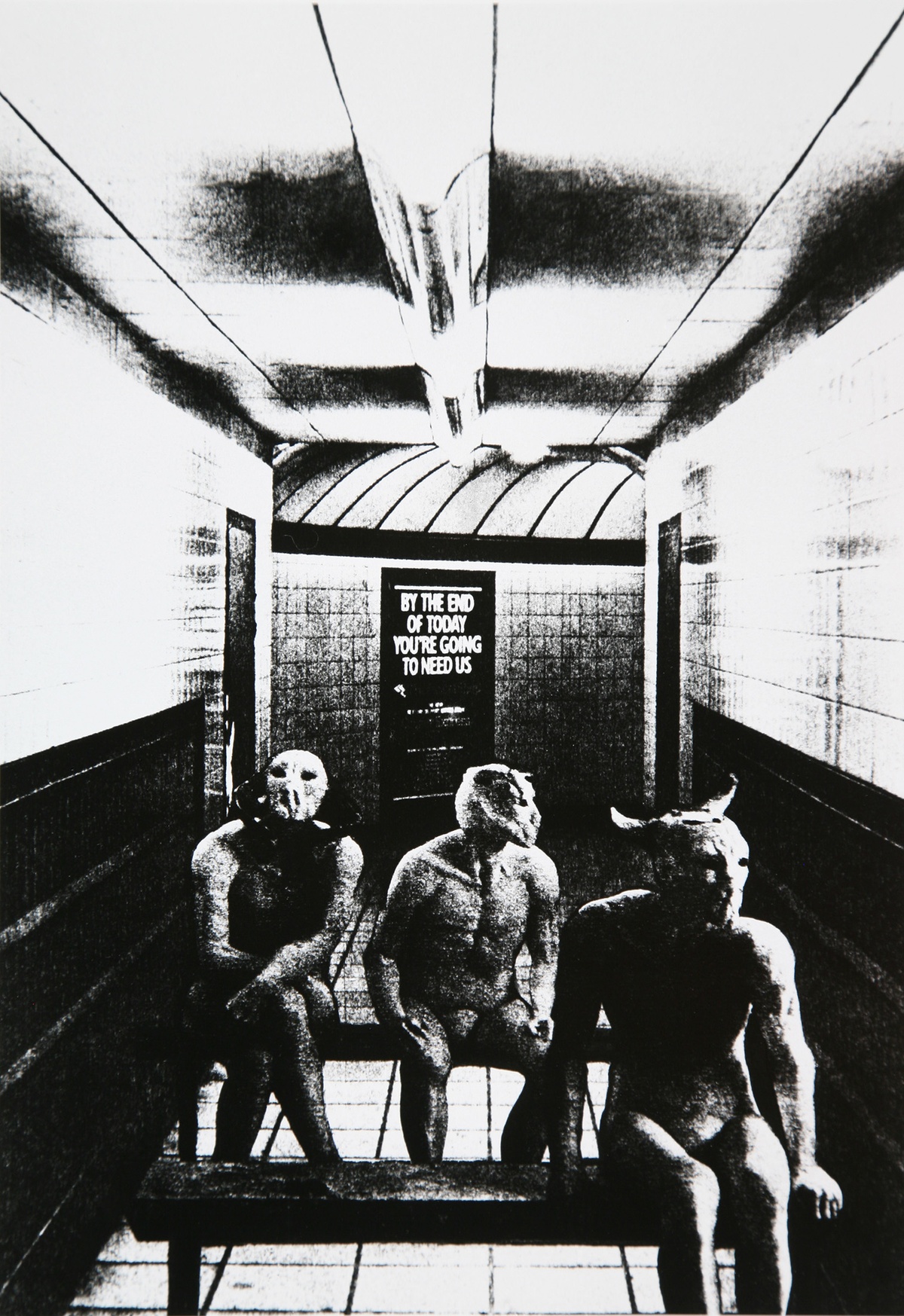

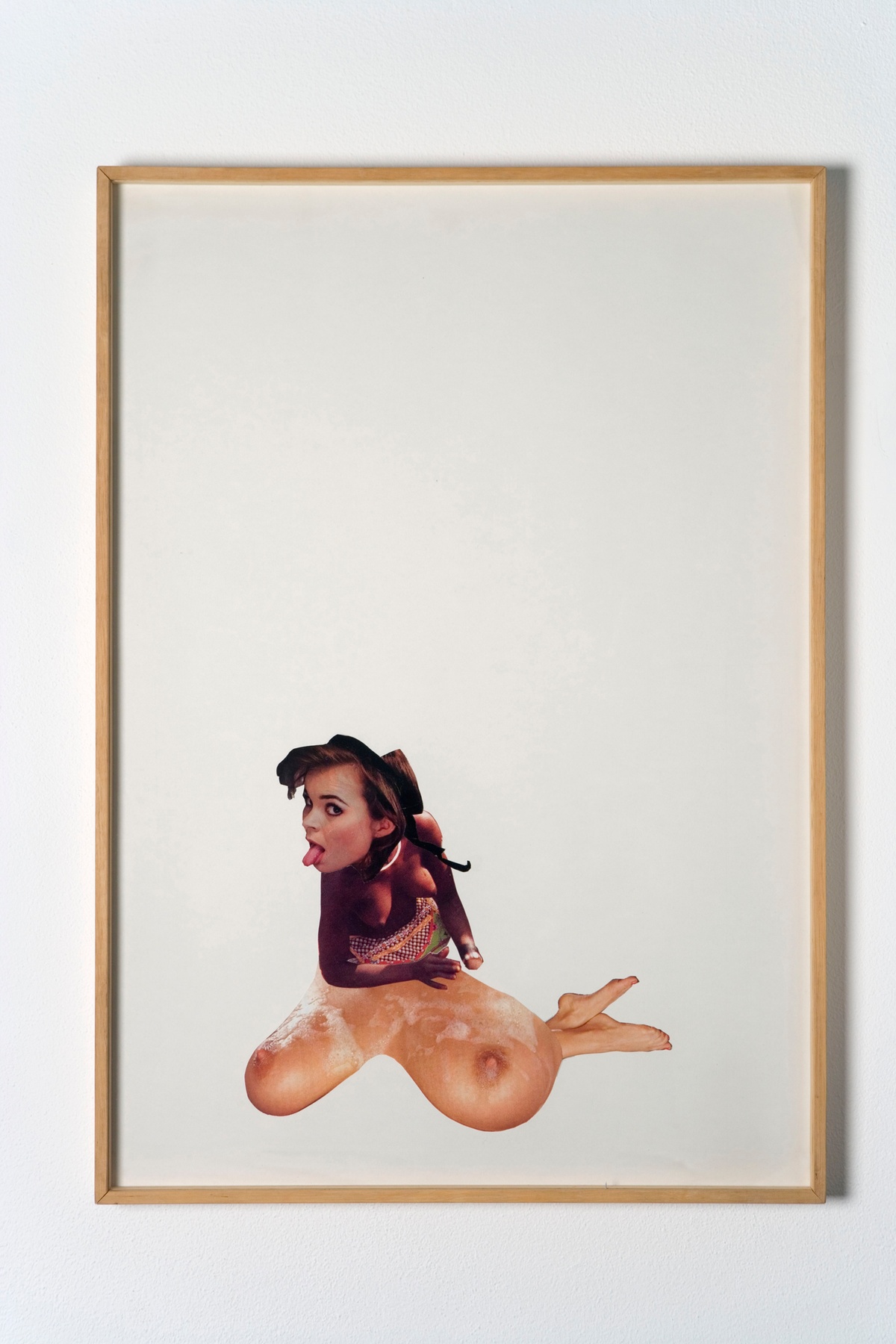

Ivor Powell: Grosz – or was it the Herzefeldes – put out a magazine, I forget the name of it. Every single edition of this magazine was separately banned. There’s a kind of sublime defiance in that, in continuing to publish the magazine… [I]t seems that, especially at the time of Berlin Dada, defiance came to represent a way of life, an aesthetic in itself. Defiance at every level – this in contradistinction to Paris Dada, which never really broke out of a concern with art… [D]oes this attitude on the part of the Weimar artists, interest or excite you in terms of its possibilities as a way of life?The Berlin Dada legacy of Hannah Höch, along with that of John Heartfield, is clearly evident in the work of Jane Alexander. A decade later, Candice Breitz applied similar strategies in her early photomontages that asked tough questions about the perceived ‘norms’ of representing women not as individual subjects but as a collection of fragmented, objectified and fetishised body parts.

Robert Hodgins: The negative side of it is that the Surrealists – in spite of the fact that they seemed to be doing 'outrageous’ things, were always backed by a very respectable avant-garde side of the aristocracy… They were never really at risk. Now that kind of public didn’t exist in Berlin. What you had in Berlin was the fact that there was really only one ruling class and that was the military.

– Ivor Powell in conversation with Robert Hodgins, 1984

Assemblage (collage’s three-dimensional equivalent and a popular Neo-Dada medium) was a medium for artists who either could not afford expensive materials or for whom the materials of art needed to reflect the climate in which they were being produced. Lucas Seage’s early assemblage sculptures, which are powerfully evocative of the abject lives of an oppressed black working class (see Coffin of the Migrant Worker, n.d.), earned him a scholarship to study with Joseph Beuys in Germany in 1981. Willie Bester’s The Soldier (1990) mirrors the violence of the late 1980s in an uncompromising way.

In a society where every aspect of the personal, including sexuality, fashion, belief systems and relationships, was politicised, the political underground had a cultural equivalent. From the late 1970s, the rebel yell of punk music was an expressive outlet for a generation of white, middle-class youth gatvol of Apartheid’s injustices and facing conscription. Collectivism took root in theatre and experimental performances, poster and mural co-operatives. ‘Alternative’ communities were formed in clubs and bars. Personal expression found form through music and zines produced on the cheap.

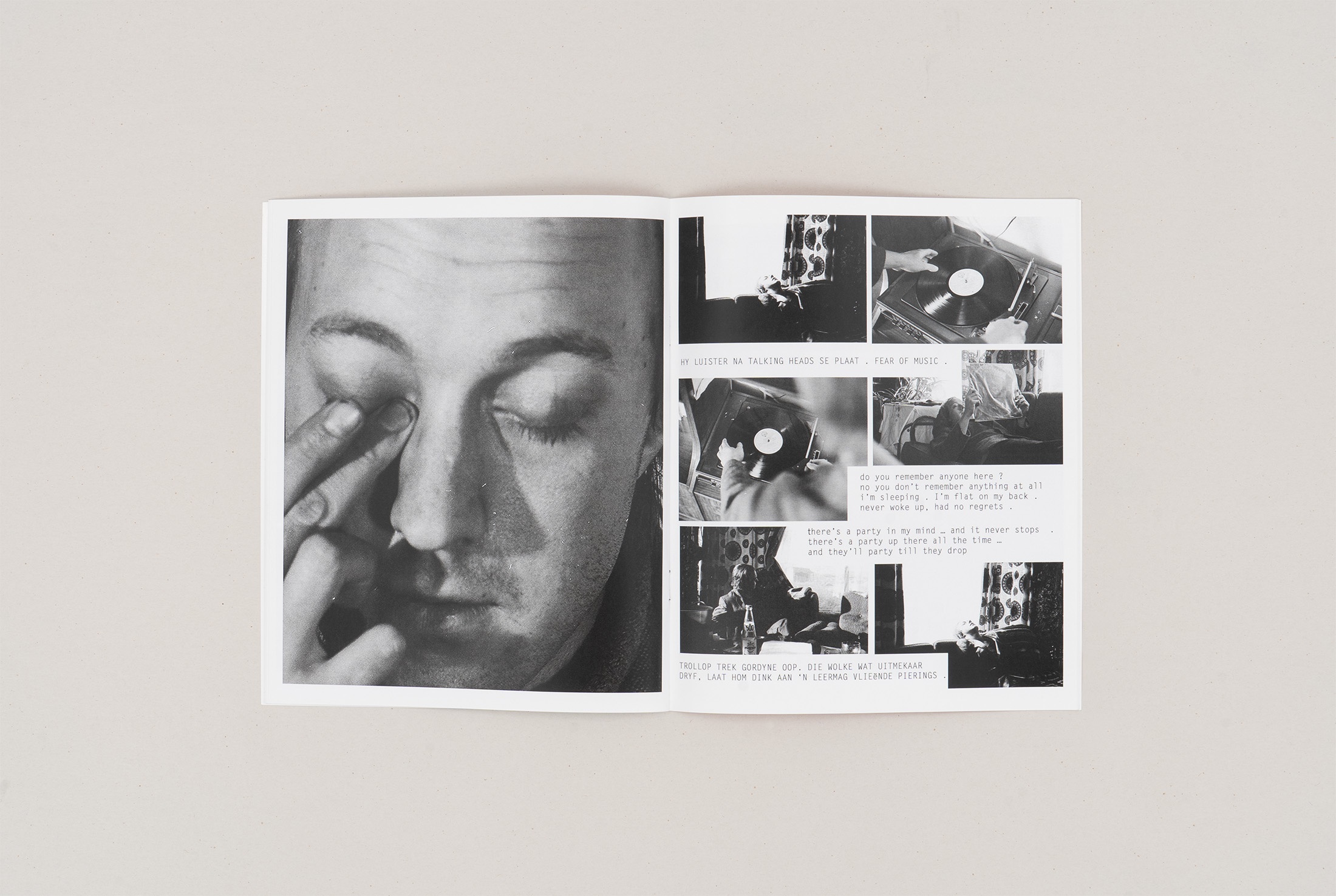

Me and Gys and Megan and Christo came from the theatre. Neil and Kendell were artists. Velile was his own man. We wanted poets to be heard and that’s why we made a hell of a noise. We didn’t want to rock. We wanted to commit murder, be unconscious. Preferably naked. To ignite the world with words. It was urgent. It was more important than anything else. We never talked politics. The political situation was obvious… We didn’t want to reason with them; we wanted to dance a twisted line.At the intersection of experimental music, art and democratic transition stood Neil Goedhals, a reserved individual whose premature death in 1990 cut short an influential, albeit short, career. Guitarist for Koos and the band’s de facto musical director, Goedhals produced a large body of experimental paintings that suggest a deep interest in the alchemical implications of formalism.

– Marcel van Heerden on Koos, 2009

New Freedoms?

As South Africa was welcomed back into the international community, the mix of tension, optimism and insecurity was a breeding ground for new creative strategies. Video, photography, installation and digital arts gained prominence. Drawing on knowledge of recent and past histories, artists worked both individually and collaboratively to critique personal, political and creative apathy. Wayne Barker’s later FIG initiative (c. 1989) and Siemon Allen’s FLAT International (1993‒95) benefitted from the space for experimentation that groups like Koos and Possession embodied.

Apartheid’s toxic legacies continue to be processed through various creative strategies. In the early 1990s, Kendell Geers introduced ‘aesthetic terrorist’ tactics. His mode of working is indebted to The Situationist International; recoded to respond to local conditions with a global perspective. Radical reappraisals of the representation of race and gender from a post-colonial perspective are evident in the work of Belinda Blignaut, Michael MacGarry and Athi-Patra Ruga. Drawing on knowledge of recent and past histories, artists work both individually and collaboratively to critique personal, political and creative apathy.

The millennial turn produced its own anxieties that uncannily echo Dada’s formative years, a generation for whom society’s corruption and exhaustion seem a golden opportunity to rethink our priorities anew. Does the collapse of capitalism mark a return to ideas and an understanding of the political imperatives of art? Dada represented freedom. It opened art up to the everyday. We are its beneficiaries, but what will we continue to make of this opportunity nearly a century later?

(Source: Exhibition panel)

Is jy ‘n moegoe / Of is jy ‘n ou

Is jy ‘n stukkie / Of is jy ‘n vrou

Are you gone / Or are you come

Are you many / Or only some

– Koos, 1989

☞ Exhibition opening

12 December 2009

Location:

Iziko South African National Gallery

Performance programming:

Lerato Bereng

Opening address:

Lesego Rampolokeng

Evening performances:

Brendon Bussy

AS IS collective

(Garth Erasmus, Manfred Zylla, Niklas Zimmer, Roderick Sauls)

Donna Kukama

Julia Raynham

Lesego Rampolokeng

Warrick Sony

Kemang wa Lehulere

Offsite installation:

Candice Breitz’s Babel Series (1999) at blank projects.

☞ Exhibition Symposium

Curators Roger van Wyk and Kathryn Smith present a special programme in the last two weeks of the exhibition, including a two-day public symposium at Rust-en-Vreugd featuring South African and visiting scholars, curators and artists.

Drawing together the first collection of historical Dada works ever seen in South Africa, as well as an eclectic range of works by South African artists representing an assortment of experimental and underground positions, the exhibition proposes a review of the ambivalent relationship between cultural creation and political resistance, as well as how art historical ideas are received and interpreted in response to specific, local conditions.

Dada South? also invites consideration of another set of questions: What significance did African art hold for Dada, and how do we understand their ideas about Africa? How are their counter-rational, collaborative and interdisciplinary strategies, dating back nearly 100 years now, still so resonant in contemporary art today? In particular, what does a Dada attitude to the political and spiritual reveal about individualism, collectivism and ethics in art today? As Marcel Duchamp said, “When you tap something, you don’t always recognise the sound. That’s apt to come later.” Could Dada be the only 20th-century movement that still exists?

As a movement founded by exiles and migrants, Dada challenged notions of territoriality, nationality, ownership and prescribed identity. Dada’s lack of allegiance to any style or ideology, as well as its political and aesthetic contrariness, offers an alternative lens through which to view creative tactics and tendencies in contexts that have experienced radical political change.

Whether we ask “What is Dada?” or “What is not-Dada?” (which is a rather Dada question), some of the topics covered include the relationship between Dada and Africa; the cultural underground and related periodicals; art practice as a tactics of action; relationships between forms of art and political agency; the tensions between institutions and experimentation; and counter-rational strategies (absurdism, chaos and chance) as methods for innovation.

(Source: Symposium invitation)

When was Dada in South Africa?

Thembinkosi Goniwe (ZA)

Dada’s Africa

Marc Dachy (FR)

Keynote

Much ado about nothing, the secret history of Fuck (bc issue 7, 2009)

Kendell Geers

The Cultural Underground and Other Invisible Histories

Stacy Hardy, Belinda Blignaut and Fred de Vries

Conversation Pit

Laban, Dada, Dancers

Jean Johnson-Jones (US/UK)

Keynote

Collective Practice as a Tactics of Action

Gugulective

The Body of the Voice

Kemang wa Lehulere, Anthea Moys, Jay Pather, Jean Johnson-Jones and Marc Dachy

Conversation Pit

Utopias, Vampires, Flagellators and Other Day-to-Day Happenings in the History of Dada South?: Disentangling myth and meaning in cultural memory.

Nina Romm

Outsider/insider fabrications

Dry Run

The Trustees (Douglas Gimberg, Christian Nerf, francis burger and Barend de Wet)

Neo-Dada: A Synthetic History

Susan Hapgood (US)

Keynote

“No island to conquer or seize, Mr Battiss!” New realist proximations between Daniel Spoerri and Walter Battiss

Wilhelm van Rensburg

Kevin Atkinson: an archive of a plural practice

Stephen Croeser

Waiting Room: The Art of Neil Goedhals

Tim Liebbrandt

Wayne Barker’s 1980s

Andrew Lamprecht

Dada-ZA

Ashraf Jamal

Chance Encounters and Psychostrategies: rethinking/repositioning experimental practices

Kendell Geers, James Sey, Nina Romm, Thembinkosi Goniwe, Colin Richards, Rosemarie Shakinovsky

Conversation Pit

Chaos, chance and the future

Willem Boshoff and André Zaaiman

Conversation Pit

Josh Ginsburg

Video performance

Trollop Slaap te Veel

Launch at YOUNGBLACKMAN

☞ The Closing, or Down with Dada

28 February 2010

Location:

Gallery Annex, Iziko South African National Gallery

Adrian Notz (Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich)

Lia Perjovschi (artist, Romania)

Performances:

John Nankin (artist, ZA)

Shelley Sacks (artist, ZA/UK)

☞ Exhibition research

Benjamin, W. (2021) One-Way Street: And Other Writings. London: Verso Books. See here.

Mallarmé, S. (2009) Divagations. Translated by B. Johnson. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. See here.

Smith, K. (2005) ‘An accidental situationist, or, what happened when Battiss thought out loud’, in Skawran, K. (ed.) Walter Battiss, Gentle Anarchist. Johannesburg: Standard Bank Gallery, pp.59–67. Available here.

Smith, K. (ed.) (2007) One Million and Forty-Four Years (and Sixty Three Days): A Sampler. Stellenbosch: SMAC Gallery. Available here.

Smith, K. (2011) ‘The Experimental Turn in the Visual Arts’, in Goniwe, T., Mojavu, M. & Pissarra, M. (eds.) Visual Century: South African Art In Context 1990–2007, Vol. 4. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, pp.119–151. Available here.

Smith, K. & Van Wyk, R. (2016) ‘Dada South? Experimentation, Radicalism and Resistance: The anatomy of an exhibition in South Africa’, in Burmeister, R., Oberhofer, M. & Francini, E. (eds.) DADA AFRICA: Dialogue with the Other. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spies, pp.198–205. Available here.

Toussaint, D. (2017) ‘Dada South? Experimentation, Radicalism and Resistance: Dada’s Legacies from South African Perspectives’, in de arte, 52(2–3), pp.53–76. Available here.

Van Wyk, R. (2011) ‘The (Non)sense of Humour: Art, subversion and the quest for freedoms’, in Pissara, M. (ed.) Visual Century: South African Art In Context 1973–1992, Vol. 3. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, pp.156–179.

Van Wyk, R. (2023) ‘Dada’s African South’, in Hegenbart, S. & Kölmel, M. (eds.) Dada Data: Contemporary Art Practice in the Era of Post-Truth Politics. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, pp.125–142.

Ballot, M. (1999) Christo Coetzee. Human & Rousseau.

Bätzner, N. (2005) Faites Vos Jeux! Kunst und Spiel Seit Dada. Hatje Cantz.

Bolliger, H., et al. (1985) Dada in Zürich. Kunsthaus Zürich/Arche Verlag.

Boshoff, W. (2007) Word Forms and Language Shapes. Standard Bank Gallery.

Dachy, M. (2006) Dada: The Revolt of Art. Harry N. Abrahams.

Dachy, M. (2005) Archives Dada Chronique. Éditions Hazan.

Dickerman, L. & Doherty, B. (2005) Dada: Zürich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris. National Gallery of Art/Distributed Art Publishers.

Dickerman, L. & Witkovsky, M. (eds.) (2005) The Dada Seminars. National Gallery of Art/Distributed Art Publishers.

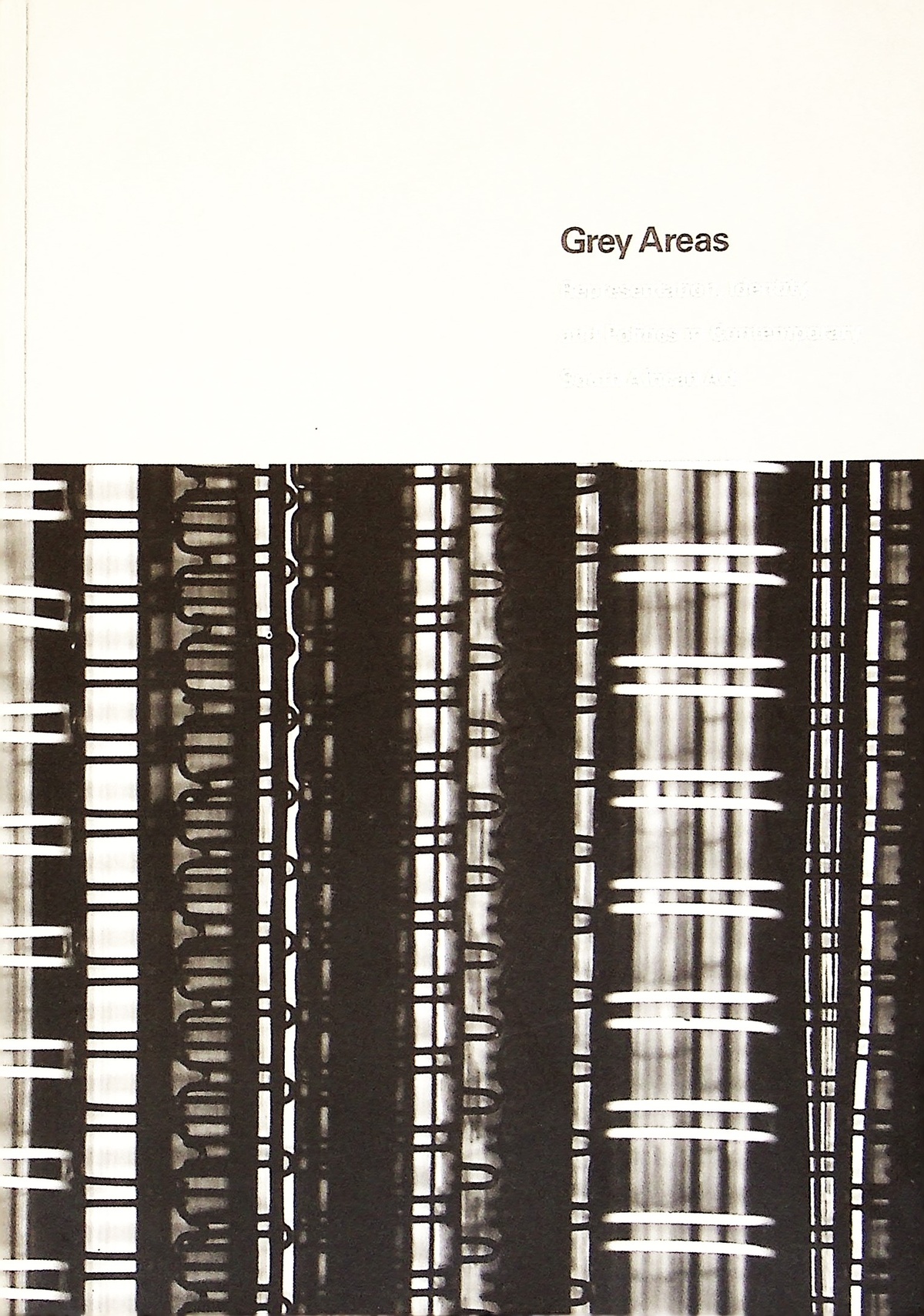

Gardiner, M. (2004) South African Literary Magazines 1956–1978. Warren Siebrits Modern and Contemporary Art.

Götz, A., et al. (1993) Collages Hannah Höch 1889–1978. Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen Stuttgart.

Green, M. (ed.) (1993) The Dada Almanac. Atlas Press.

Hapgood, S. (1994) Neo-Dada: Redefining 1958–62. American Federation of Arts/Universe Publishing.

Hopkins, P. (2006) Voëlvry: The Movement that Rocked South Africa. Zebra Press.

Jensma, W. (1977) I must show you my clippings. Ravan Press.

Jones, D. (2006) Dada Culture: Critical Texts on the Avant-Garde. Editions Rodopi B.V.

Goedhals, N. & Van Heerden, M., et al. (2009) KOOS: 1986–1990. One F Music.

Powell, I. (1984) ‘“One of my own fragments”: An Interview with Robert Hodgins’, in de arte, 31, pp.36–45.

Powell, I. (2006) ‘Violence, Vodka and Voodoo’, in Art South Africa, 5(1), pp.38–41.

Power, N. (2009) ‘Intelligence Agency: Sylvère Lotringer’, in Frieze, 125, pp.104–107.

Proud, H. (2008) ‘Neville’s Notions’, in Art South Africa, 7(2), pp.80–83.

Meyer, R., et al. (1994) Dada global. Kunsthaus Zürich/Limmat Verlag.

Motherwell, R. (ed) (1989) The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology. Belknap/Harvard.

Sandqvist, T. (2006) Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire. MIT Press.

Zweifel, S, et al. (eds.) (2006) In Girum Imus Nocte Et Consumimur Igni – The Situationist International (1957–1972). JRP Ringier.

The Dada South? symposium and closing weekend event were made possible through the additional generosity of Vivien Cohen, Culturesfrance, Pro Helvetia, Goodman Gallery, Iziko Museums of Cape Town, and the Romanian Cultural Institute, Bucharest.

Media design strategy and Exhibition Guide production:

serialworks

Research assistant:

francis burger

Translation of exhibition texts:

Bohle Conference & Language Services

Translation of Dada statements:

Barend de Wet

Unathi Sigenu

Copy-editing:

Ryan van Huyssteen

Installation designer and carpenter:

Douglas Gimberg

Installation technicians:

Denzel Deacon

Kelly Gough

Assistants:

Stuart Buttle

Anja de Klerk

Lyn Siebörger

Dawie van Vuuren

Niklas Zimmer

Specialist book sales and orders:

The Book Lounge