Flight Paths

Kathryn Smith & Roger van Wyk

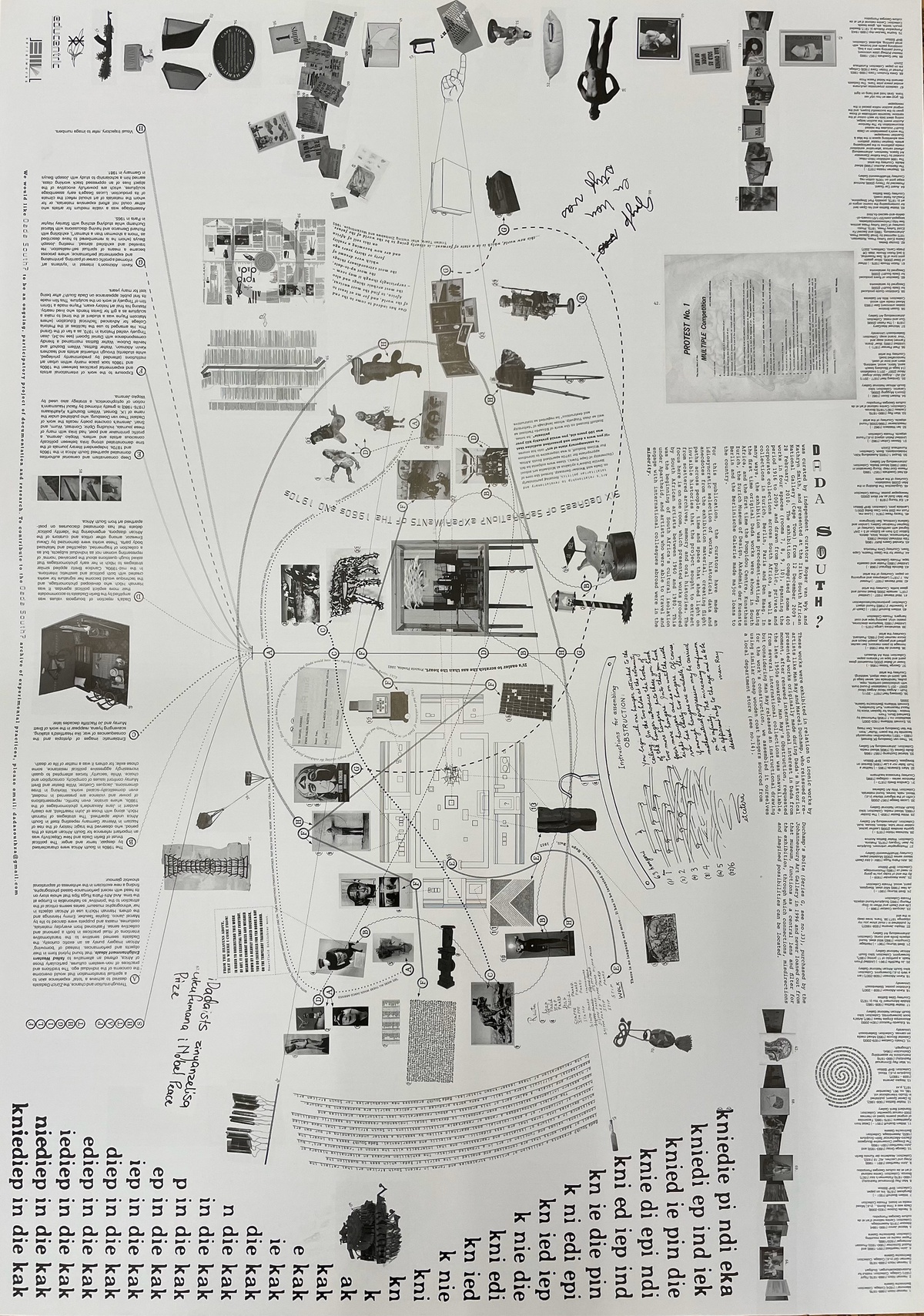

An idionsyncratic selection of works, historical data and anecdotes from the Dada South? (2009–2010) exhibition mapped out in the retroactive Flight Paths (2011) guide is compiled in this path by Alana Blignaut. Taking the Six Degrees of Separation exhibition room as a point of departure, it sheds light on connections between historical Dada artists and the South African artists that took inspiration from them during the late 1950s onwards. – September 26, 2025

Through intuition and chance, the Zürich Dadaists desired to achieve a ‘total’ experience akin to a spiritual transformation that would overcome the concerns of the individual ego.

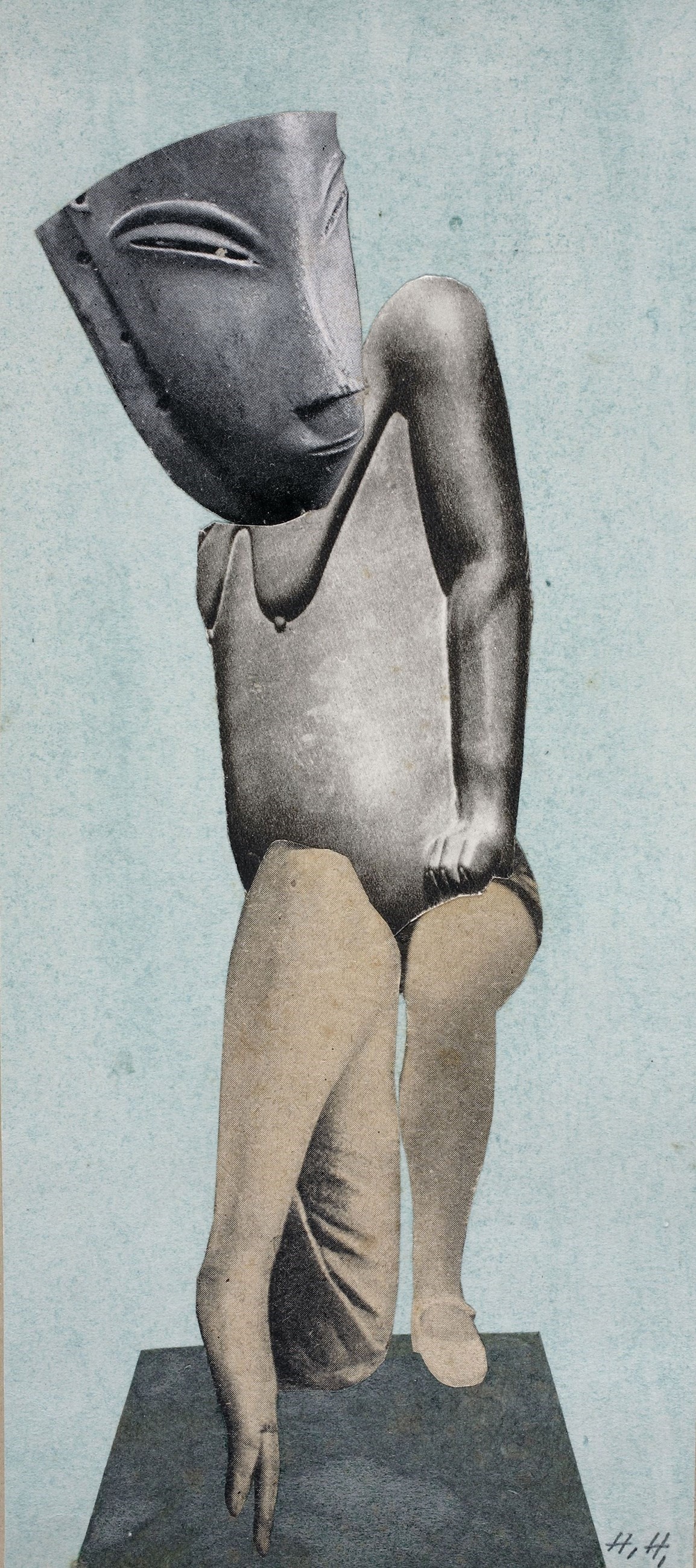

The traditions and practices of non-Western cultures, particularly those of Africa, offered an alternative to failed Western Enlightenment ideals, that found hybrid form in their objects and performances. Instead of ‘borrowing’ African imagery purely as an exotic curiosity, the Dadaists seemed sensitive to the transformative intentions of ritual practices in both a personal and collective sense.

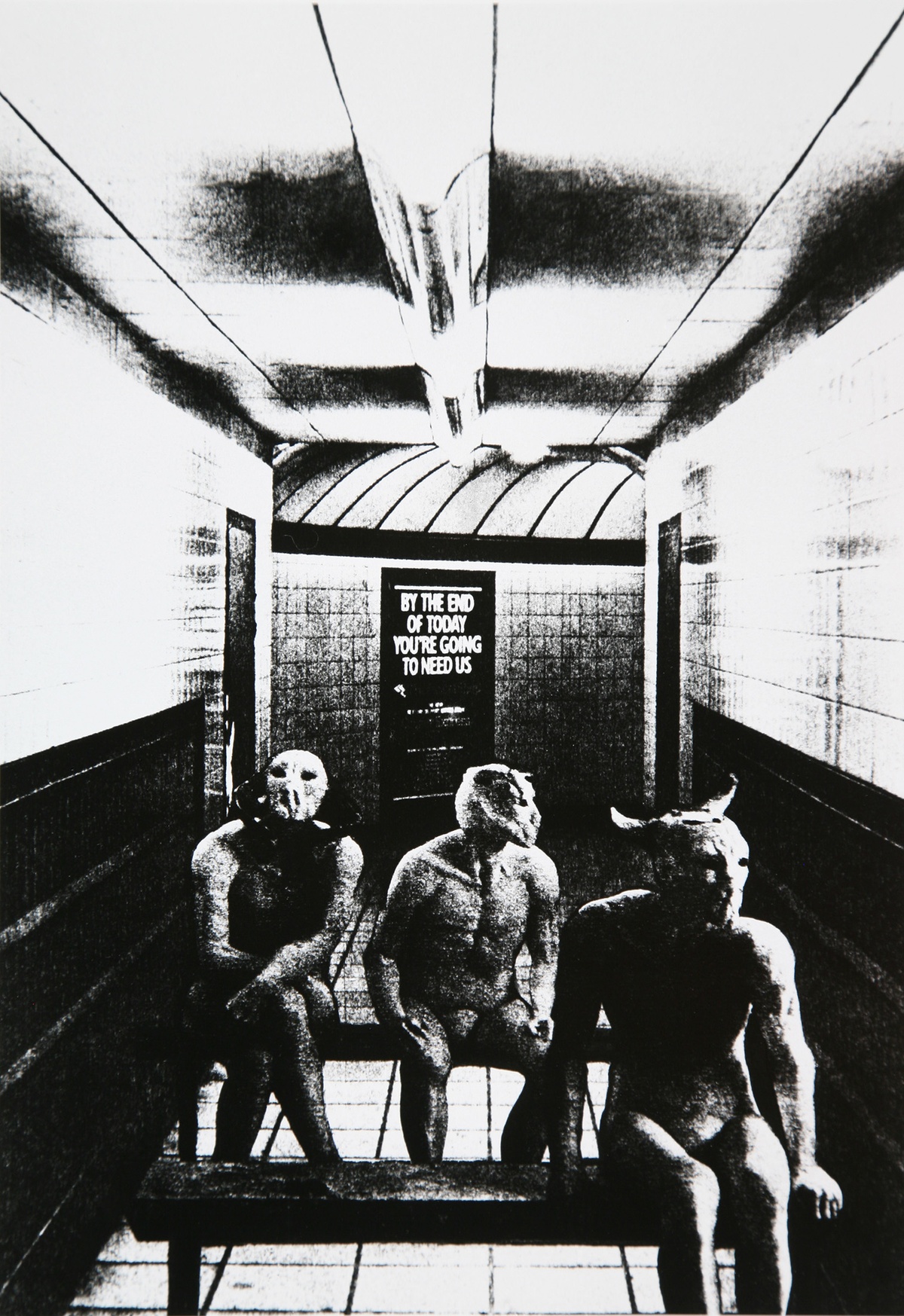

Fashioned from everyday materials, costumes, masks and puppets were danced to life by Marcel Janco, Sophie Taeuber, Emmy Hennings and the others.

We were all there when Janco arrived with his masks, and everyone immediately put one on. Then something strange happened. Not only did the mask immediately call for a costume; it also demanded a quite definite, passionate gesture…they represent not human characters and passions, but…passions that are larger than life. The horror of our time, the paralysing background of events, is made visible.– Hugo Ball, 1916

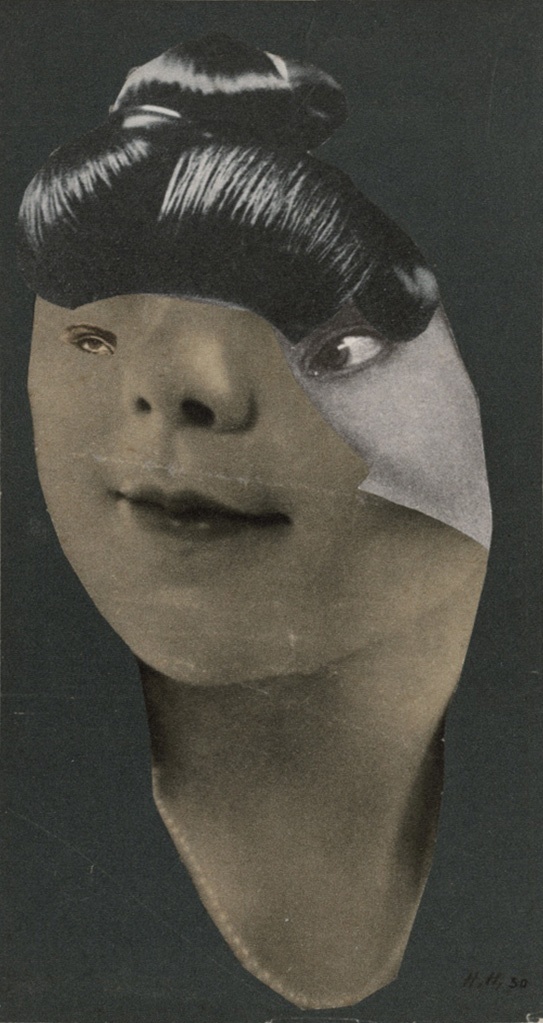

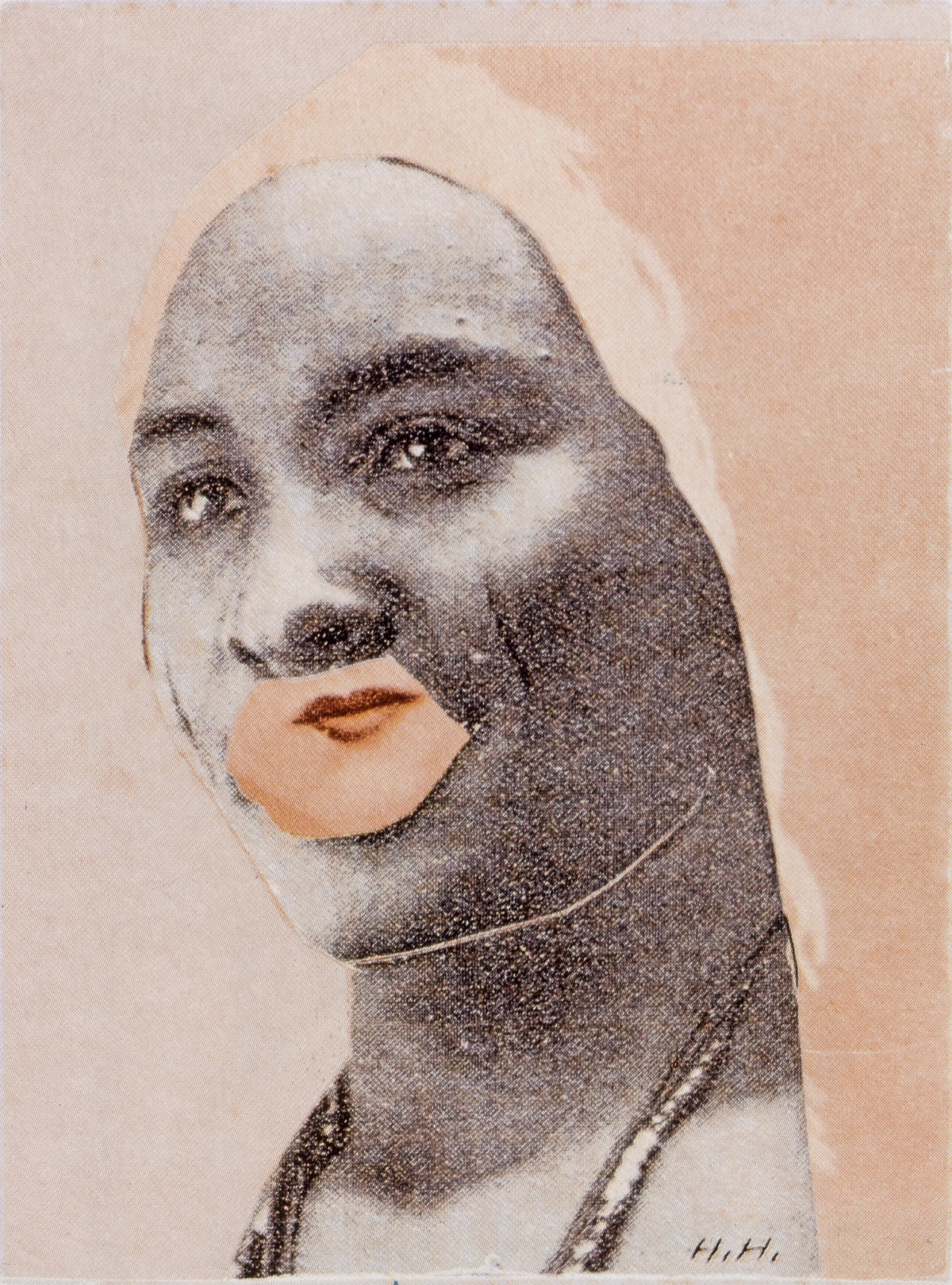

Hannah Höch’s use of African objects in her ‘ethnographic museum’ series seems critical of the attraction to the ‘primitive’ so fashionable in Europe at the time.

And Athi-Patra Ruga flips that whole story on its head with more recent performance-based photographs, finding a new exoticism in the whiteness of aspirational showbiz glamour.

The 1980s in South Africa were characterised by despair, terror and anger.

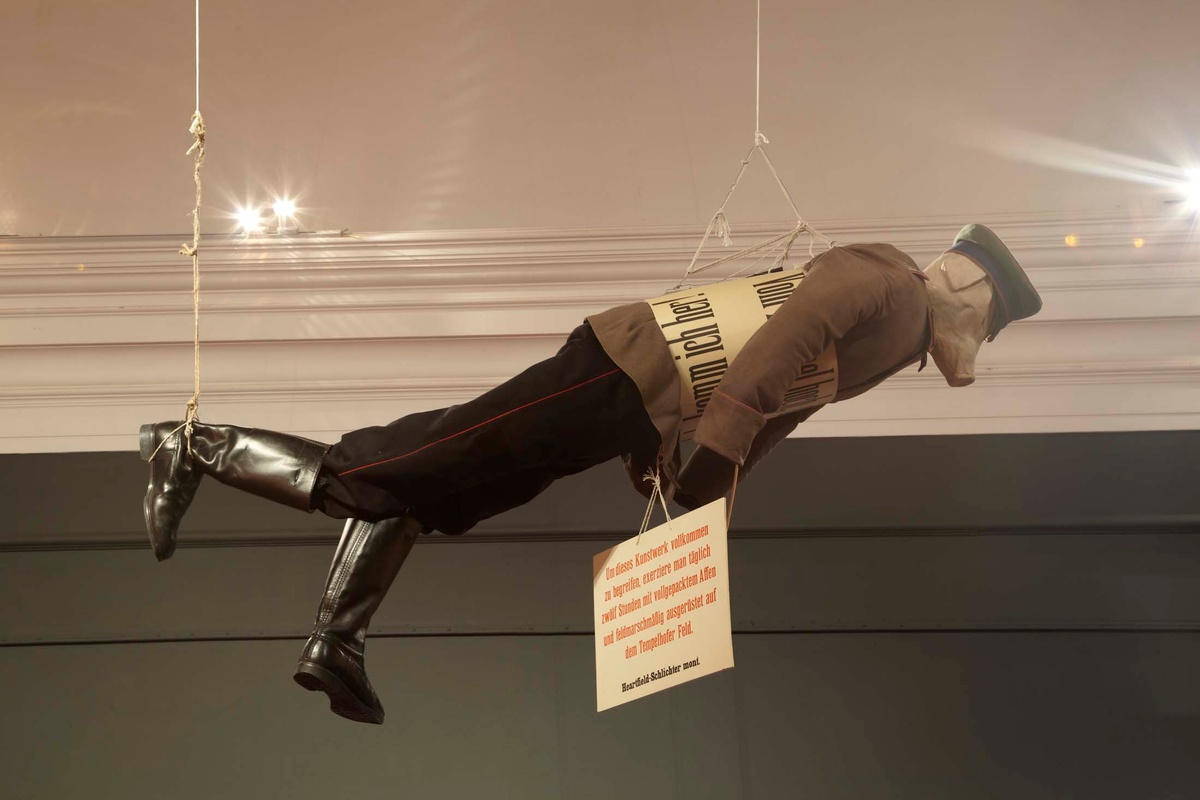

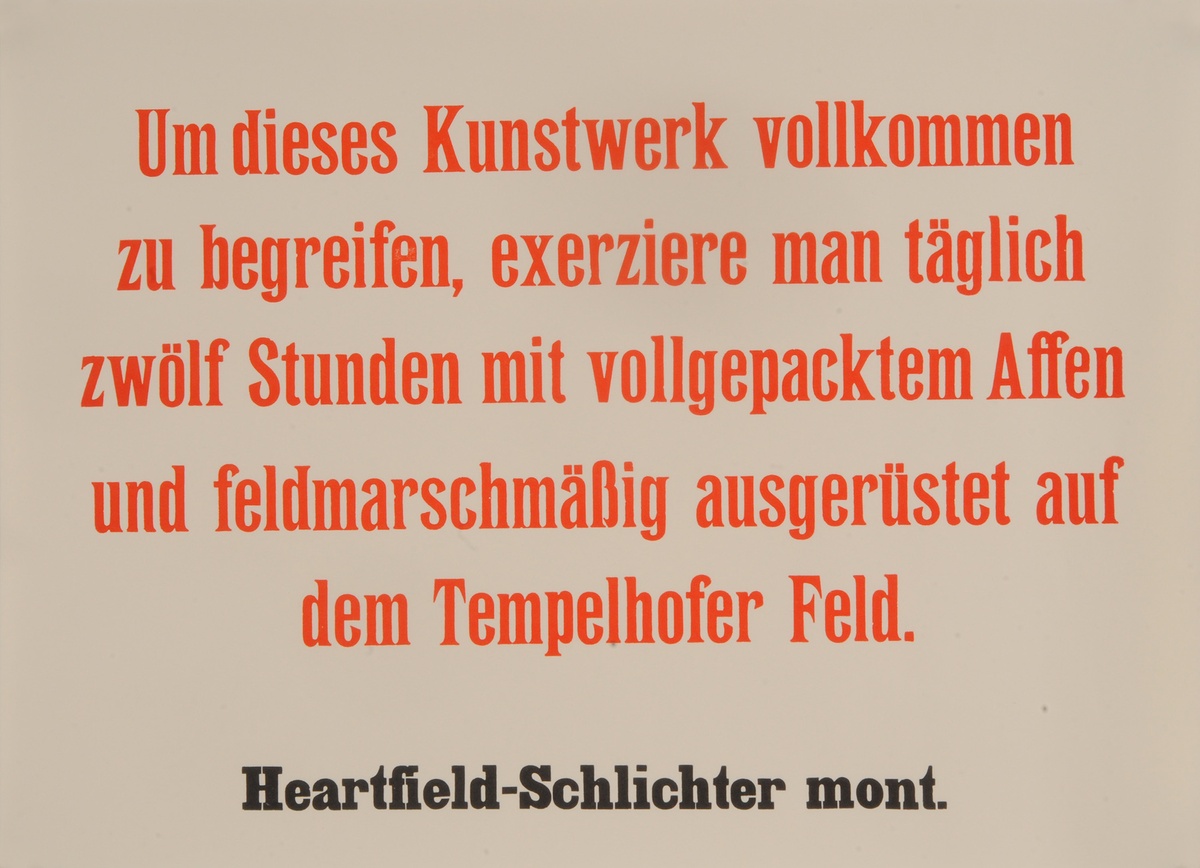

The political thrust

of Berlin Dada and New Objectivity was an important reference for South African artists of this period, who observed the tragic history of the rise of Nazism in Weimar Germany repeating itself in South Africa under apartheid.

The strategies of Hannah Höch, along with those of John Heartfield, are clearly evident in Jane Alexander’s photomontages of the 1980s, where sinister, even horrific, representations of power and violence are presented in modest, even domestically-scaled works.

Working in three dimensions, Jacques Coetzer, Willie Bester and Brett Murray confront issues of complicity, conscription and choice.

While ‘security’ forces attempted to quash increasingly aggressive political resistance, some chose exile; for others, it was a matter of life or death.

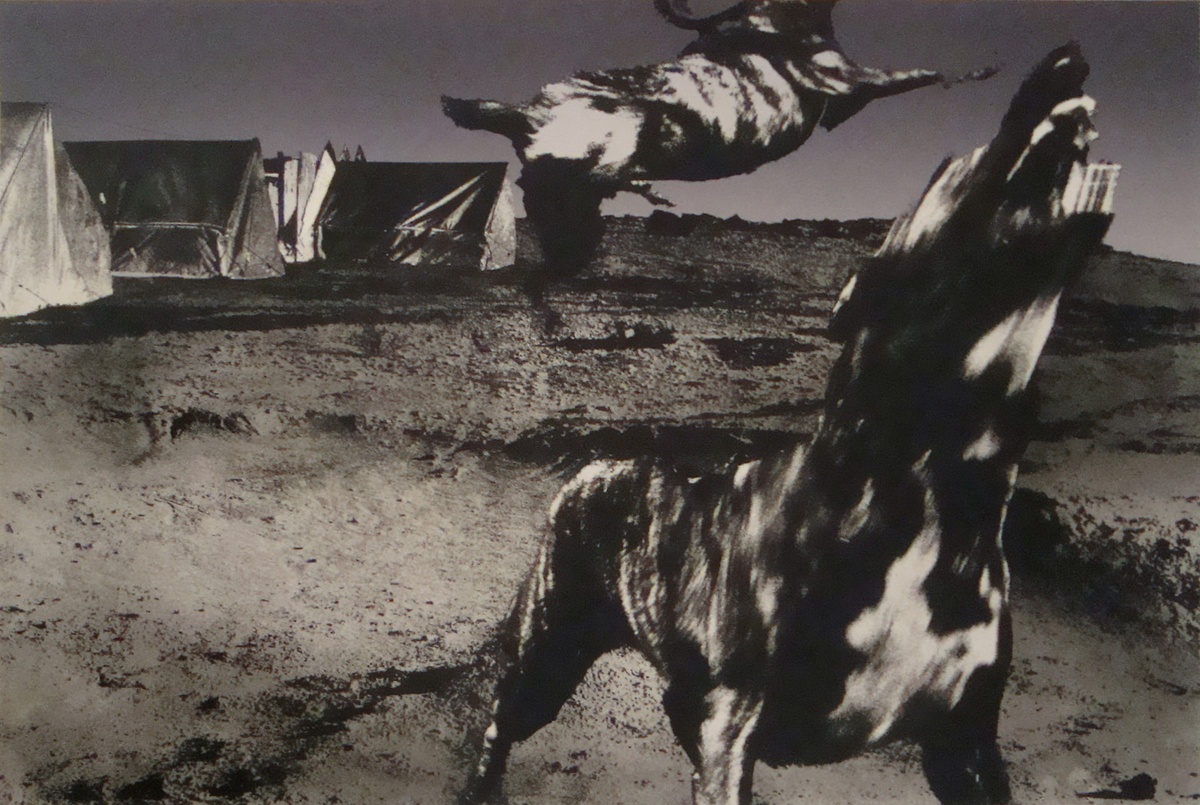

Emblematic images of dystopia and the consequences of war, like Heartfield’s stalking, scavenging hyena, reappear in the work of Brett Murray and Jo Ractliffe decades later.

Dada’s rejection of bourgeois values was amplified by the Berlin Dadaists to accommodate their more explicit political agendas. It was Hannah Höch who developed photomontage, and the technique would become her signature for works created with both political and aesthetic intentions.

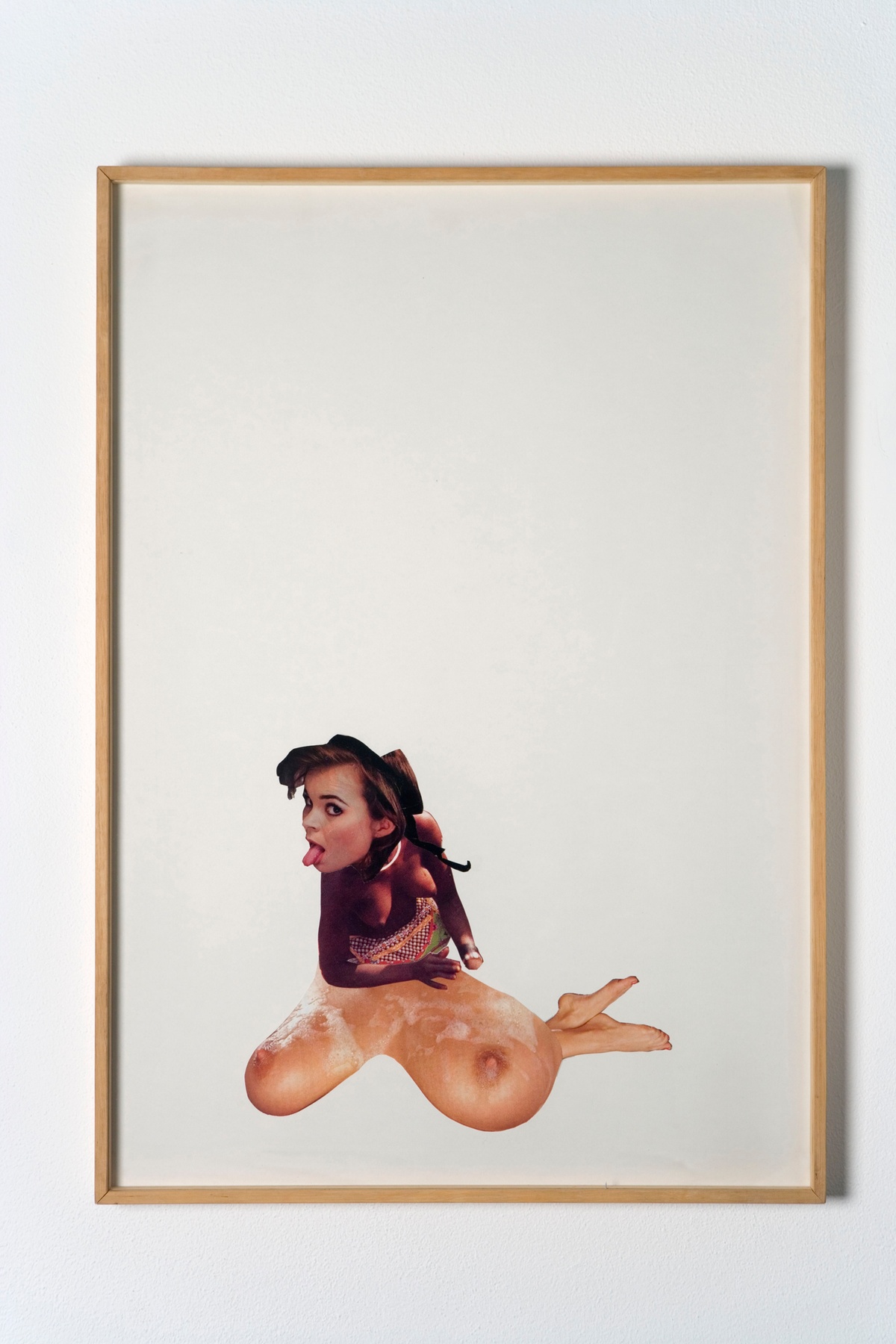

In the mid-1990s, Candice Breitz applied similar strategies to Höch in her early photomontages that asked tough questions about the perceived ‘norms’ of representing women not as individual subjects but as a collection of fragmented, objectified and fetishised body parts.

These works were demonised by Okwui Enwezor, among other critics and curators of the African diaspora, engendering the ‘identity politics’ debate that has dominated discourses on post-apartheid art from South Africa.

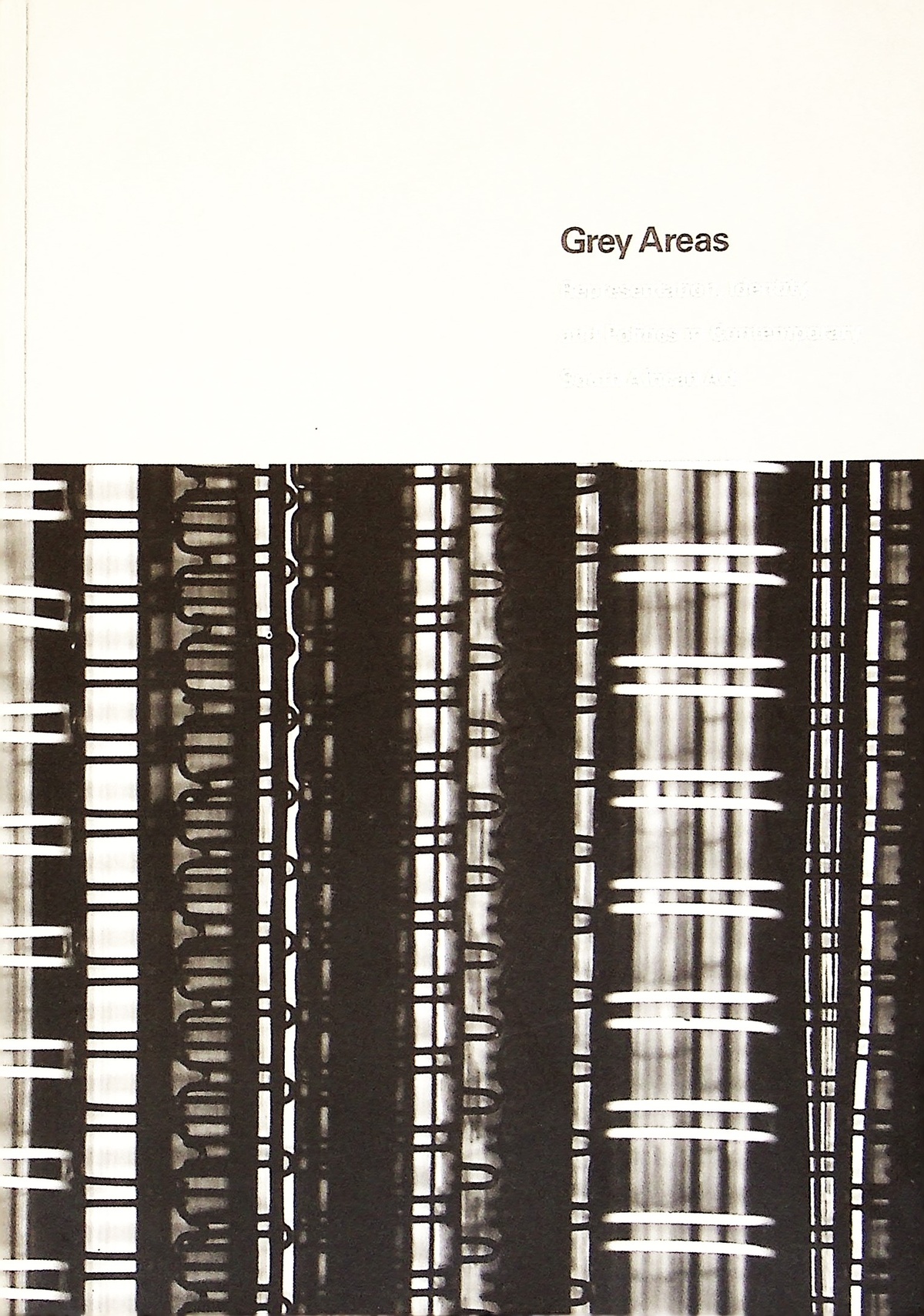

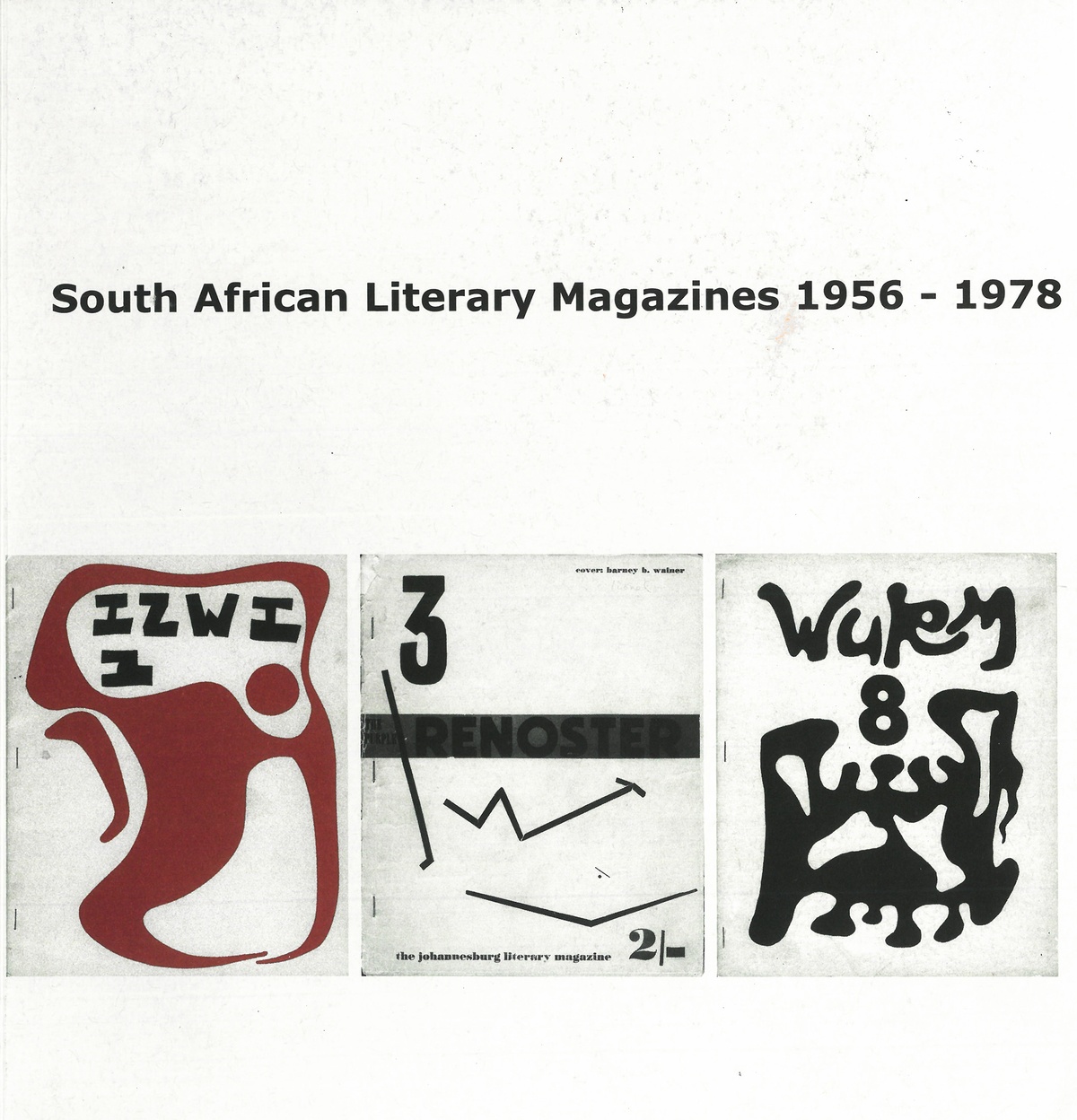

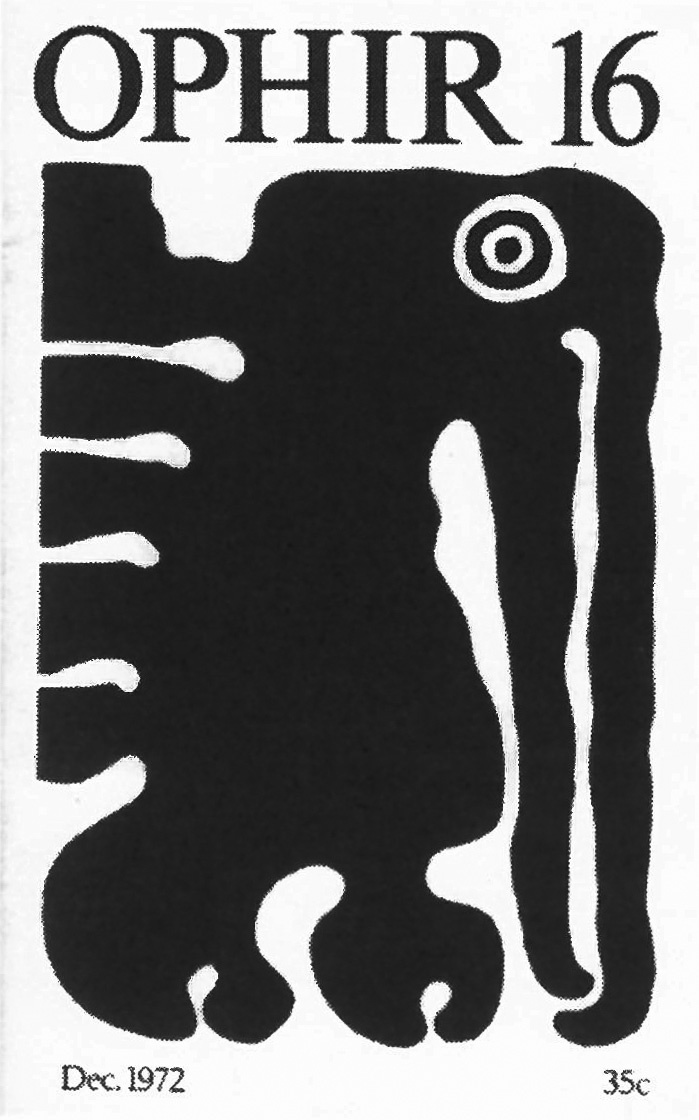

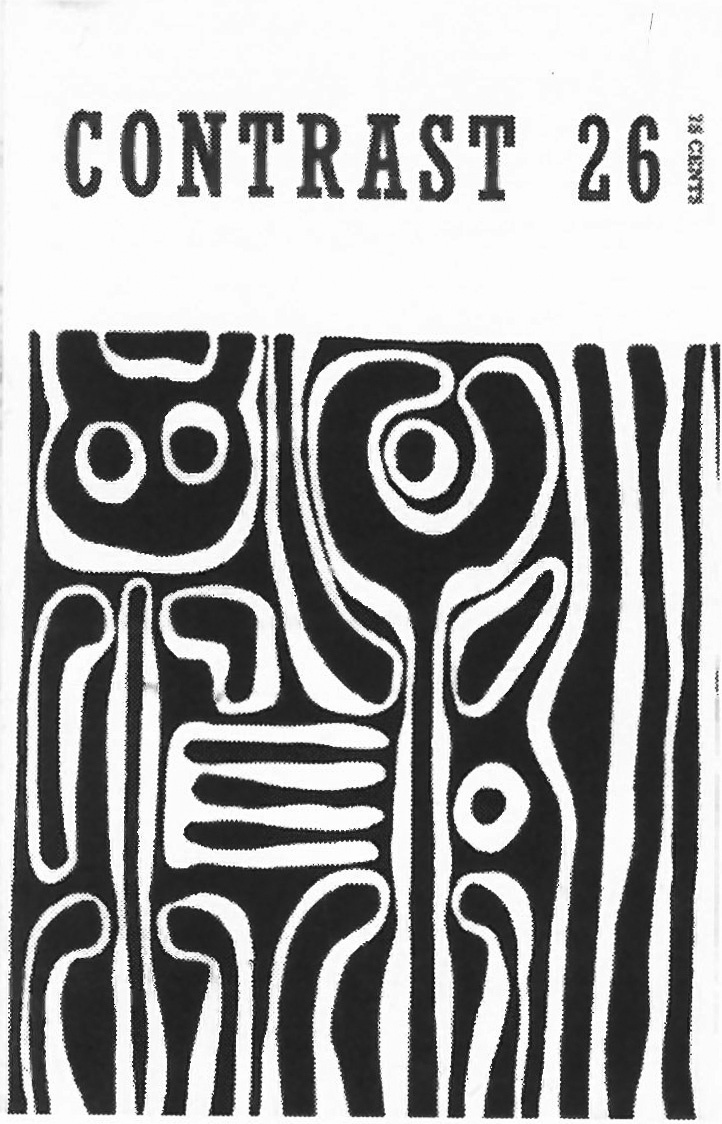

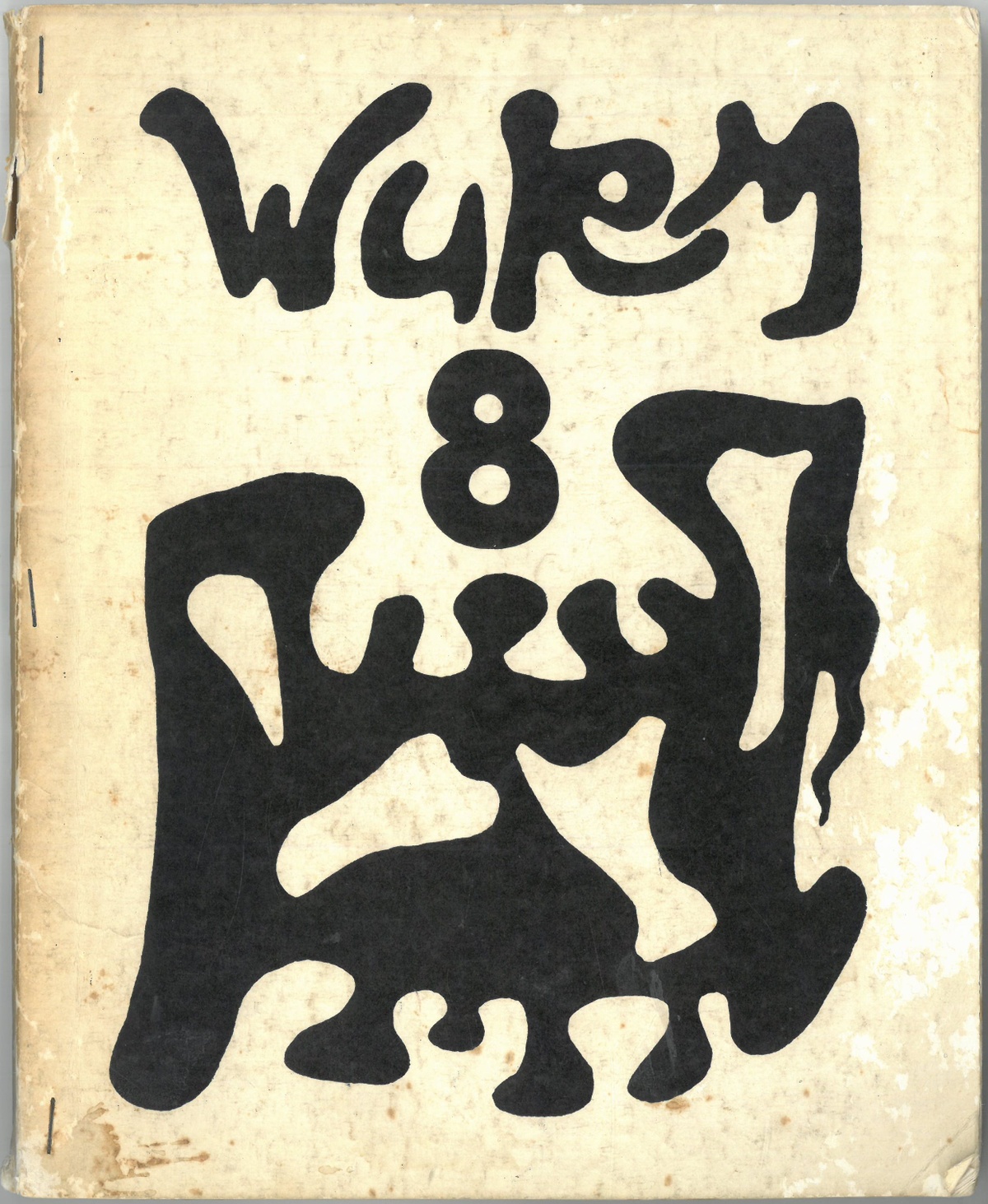

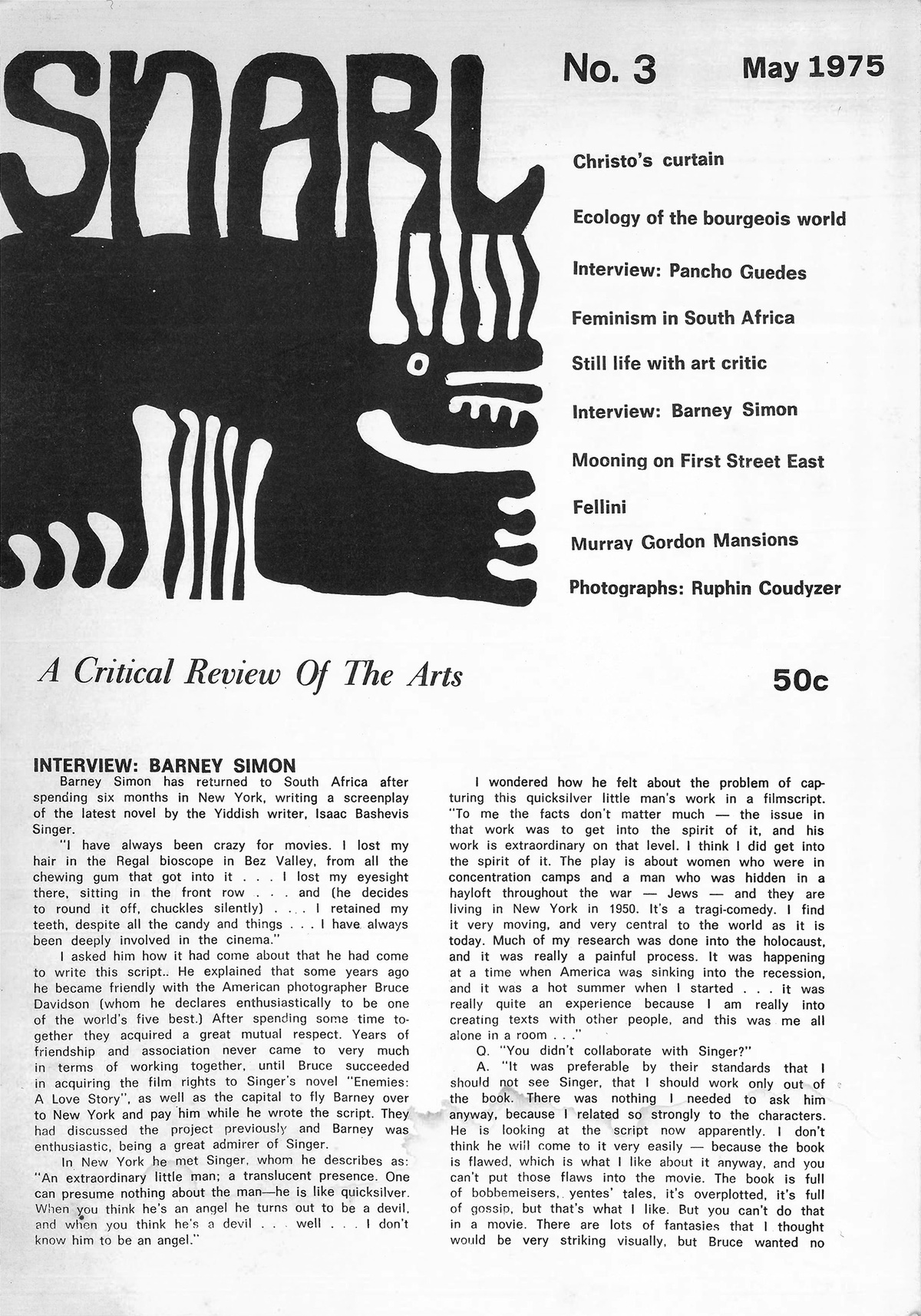

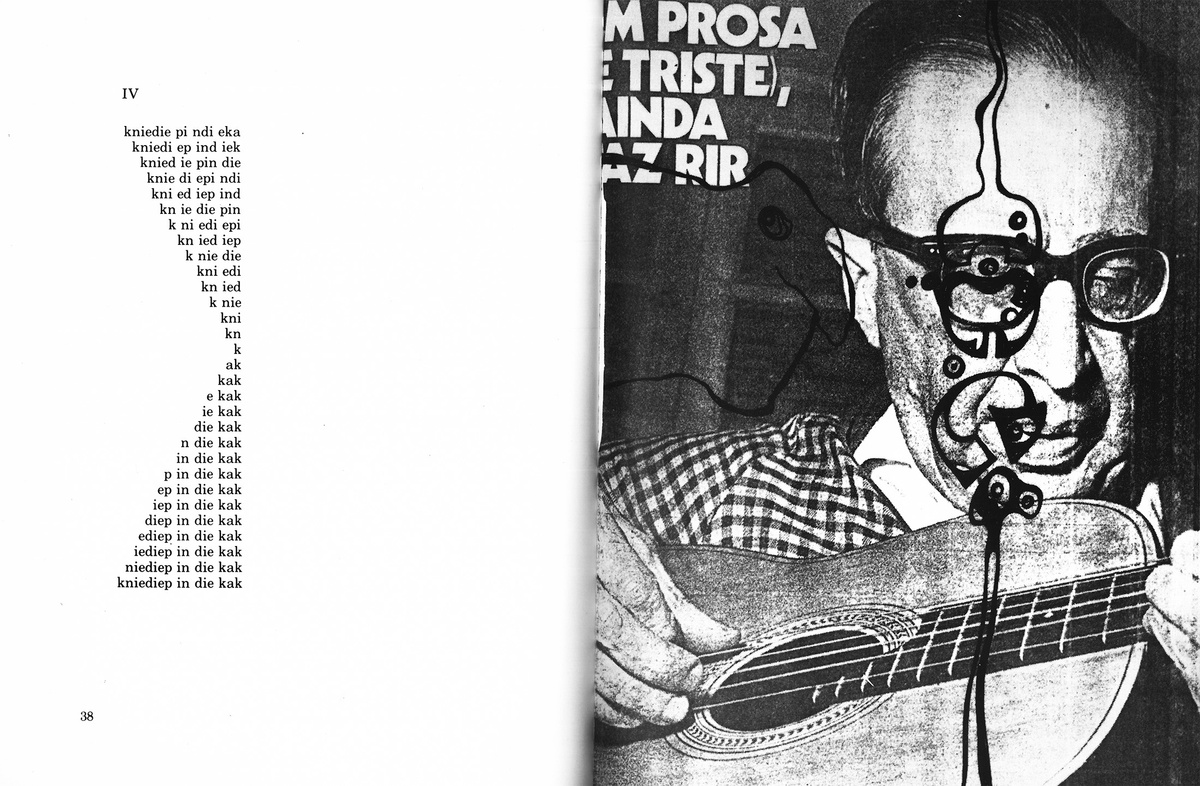

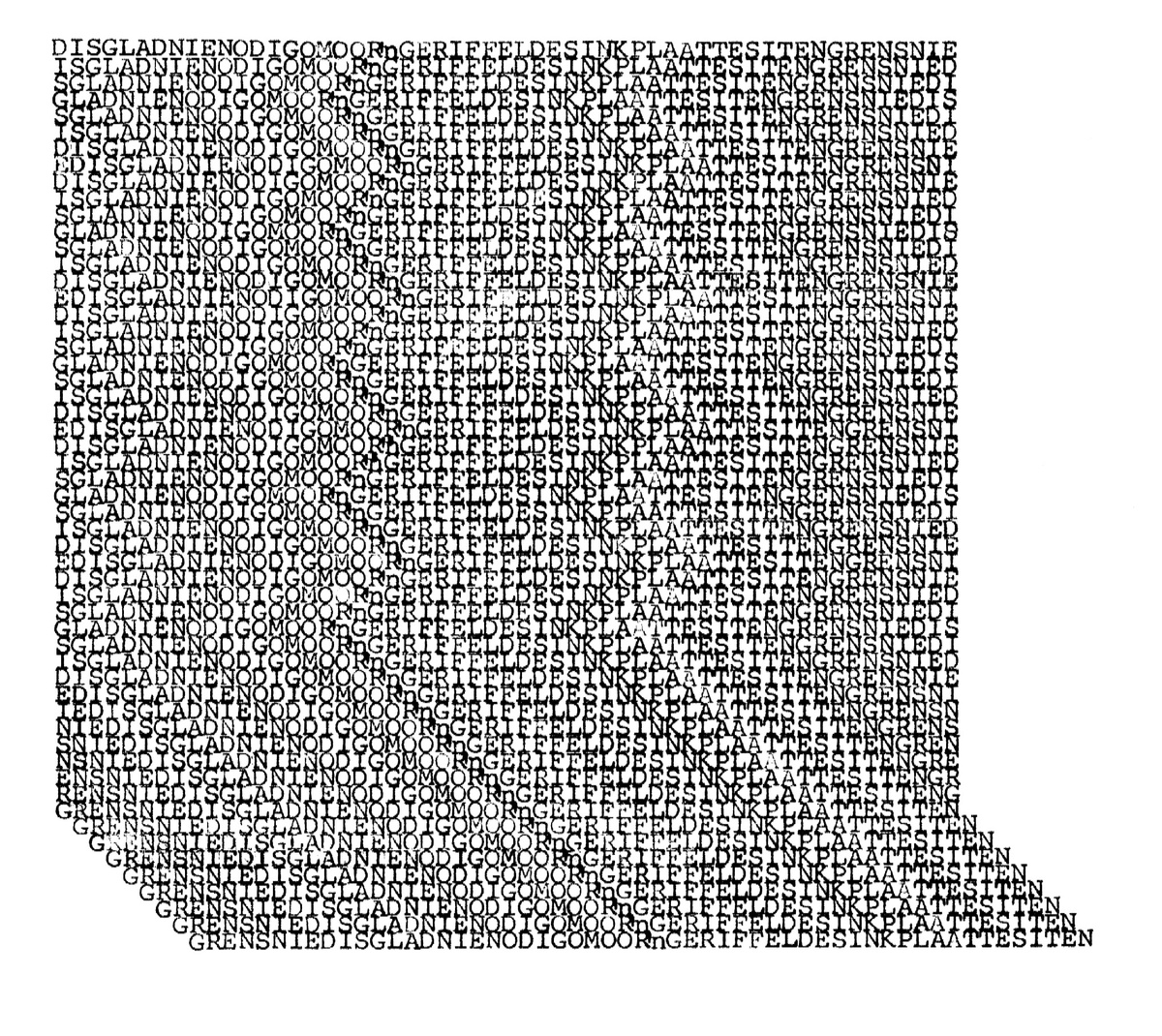

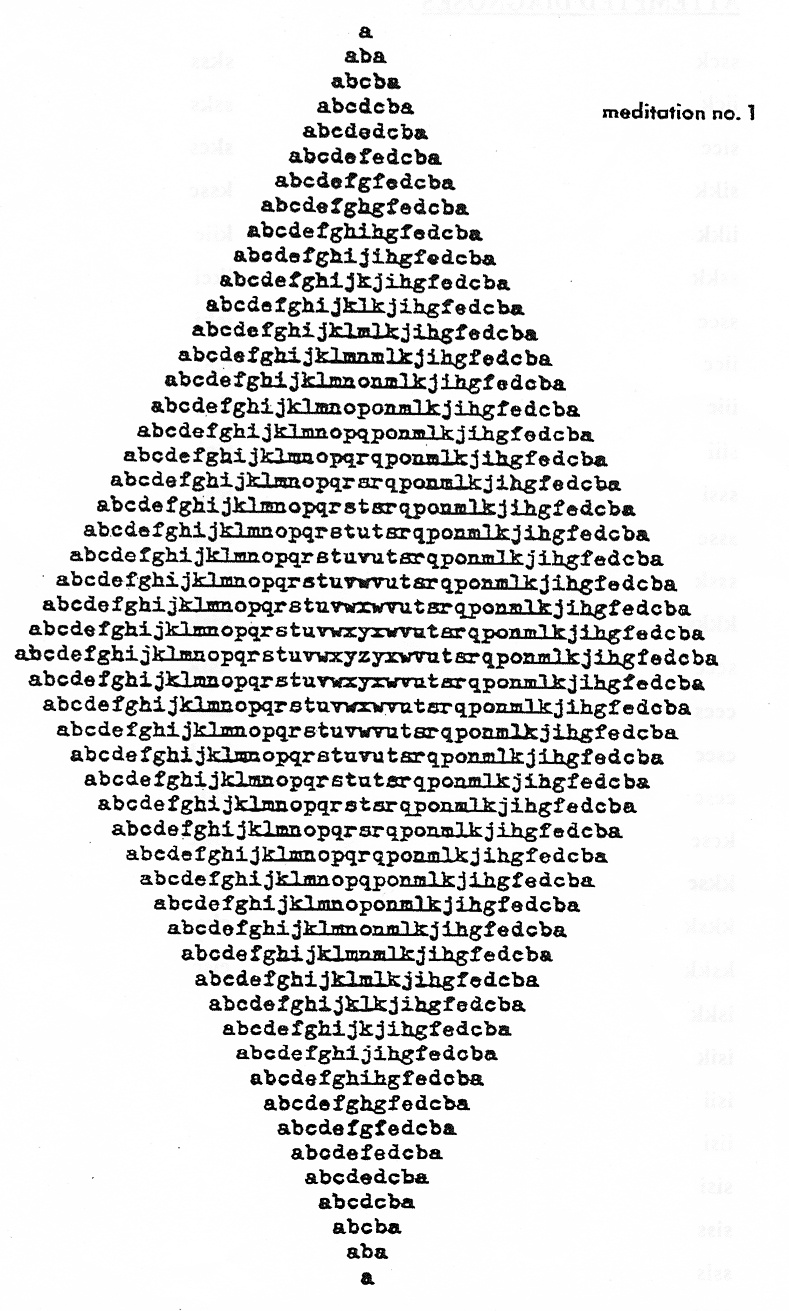

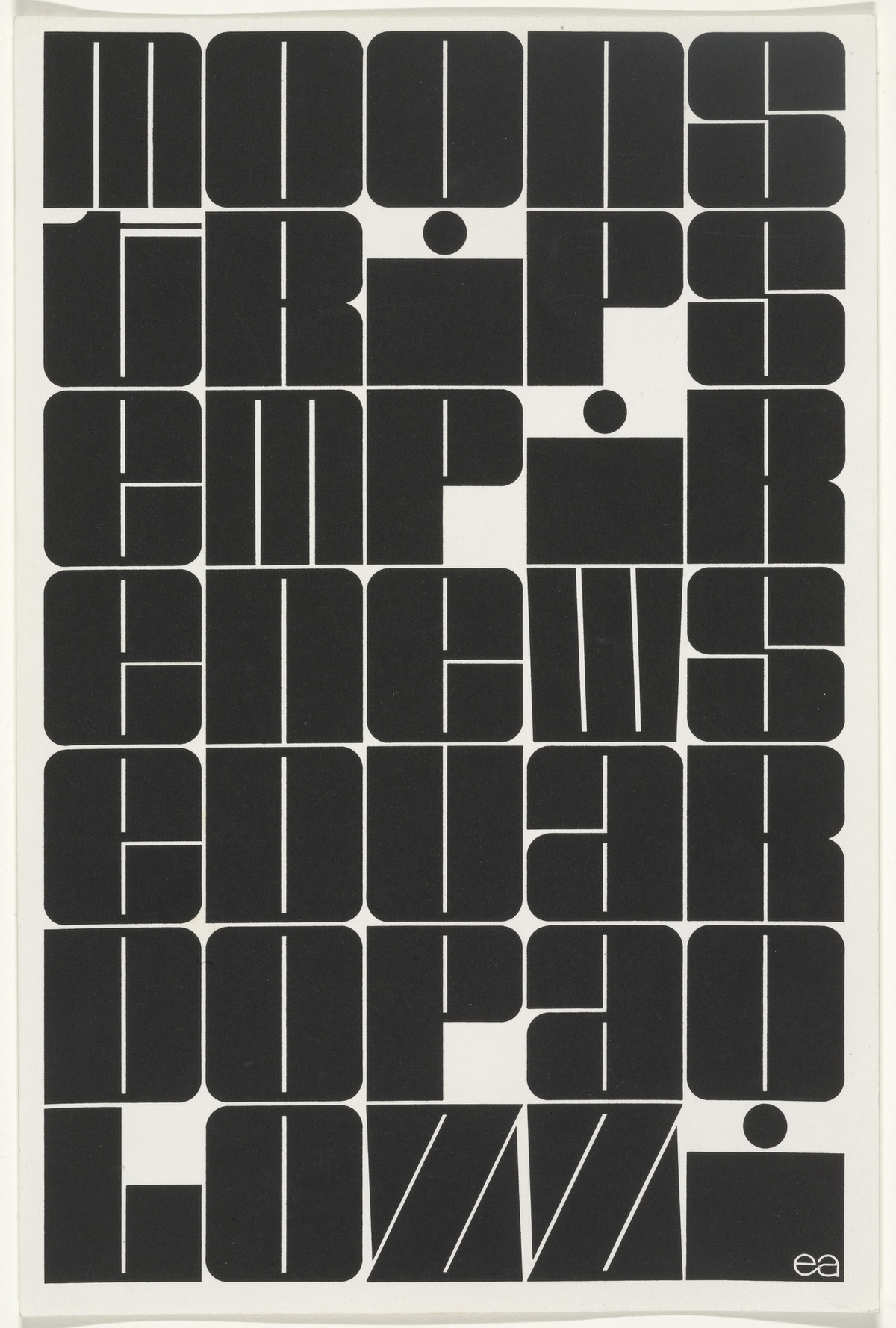

Deep conservatism and censorial authorities dominated apartheid South Africa in the 1960s and 1970s. Independent literary journals of the time demonstrated strong links between politically conscious artists and writers.

Wopko Jensma, a prolific printmaker and poet, had links with many of these journals, including Ophir, Contrast, Wurm, and Snarl.

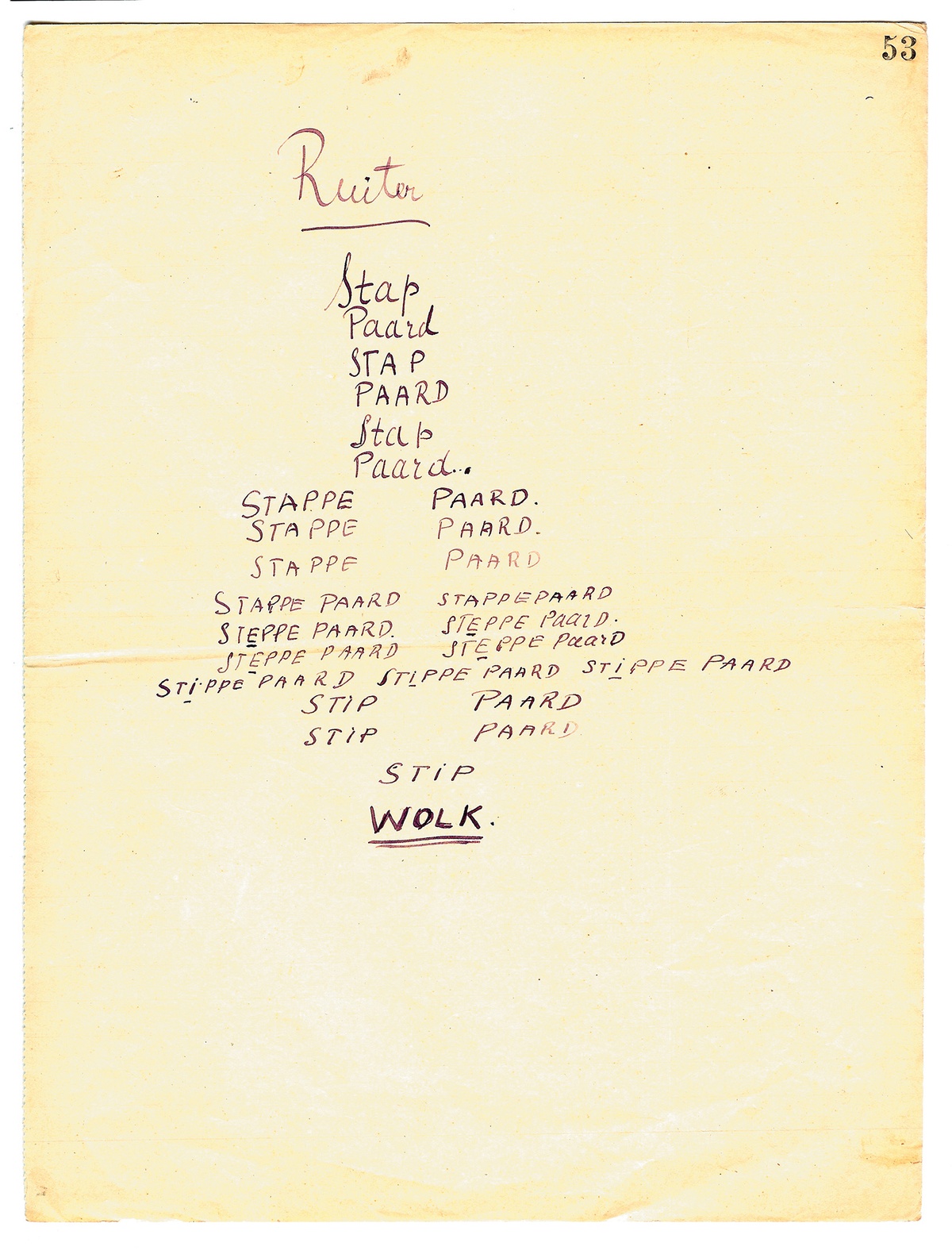

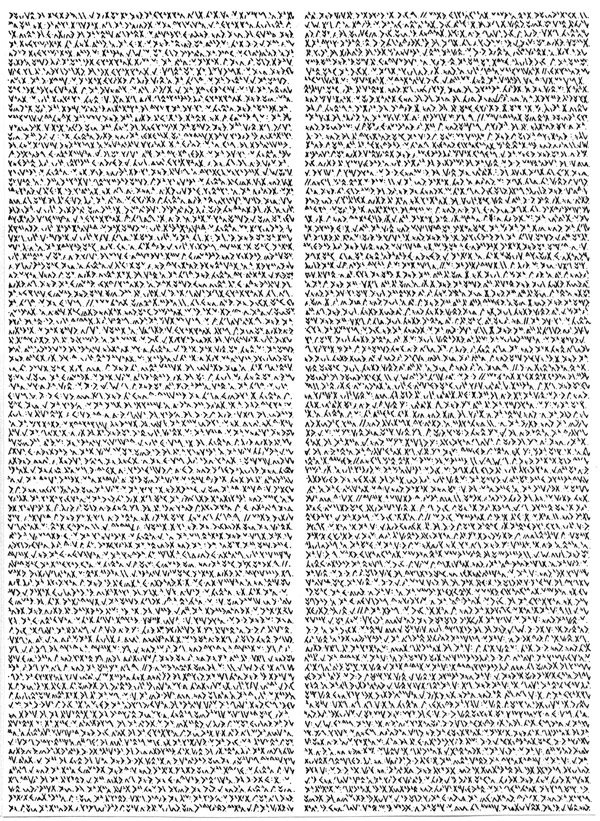

Jensma’s concrete poetry recalls the work of Dadaist Theo van Doesburg, who published under the name of I.K. Bonset.

There is no language any more… It has to be invented all over again.

– Hugo Ball, 1927

Willem Boshoff’s Kykafrikaans (1976–1980) is greatly informed by Raoul Hausmann’s notion of optophonetics, a strategy also used by Wopko Jensma.

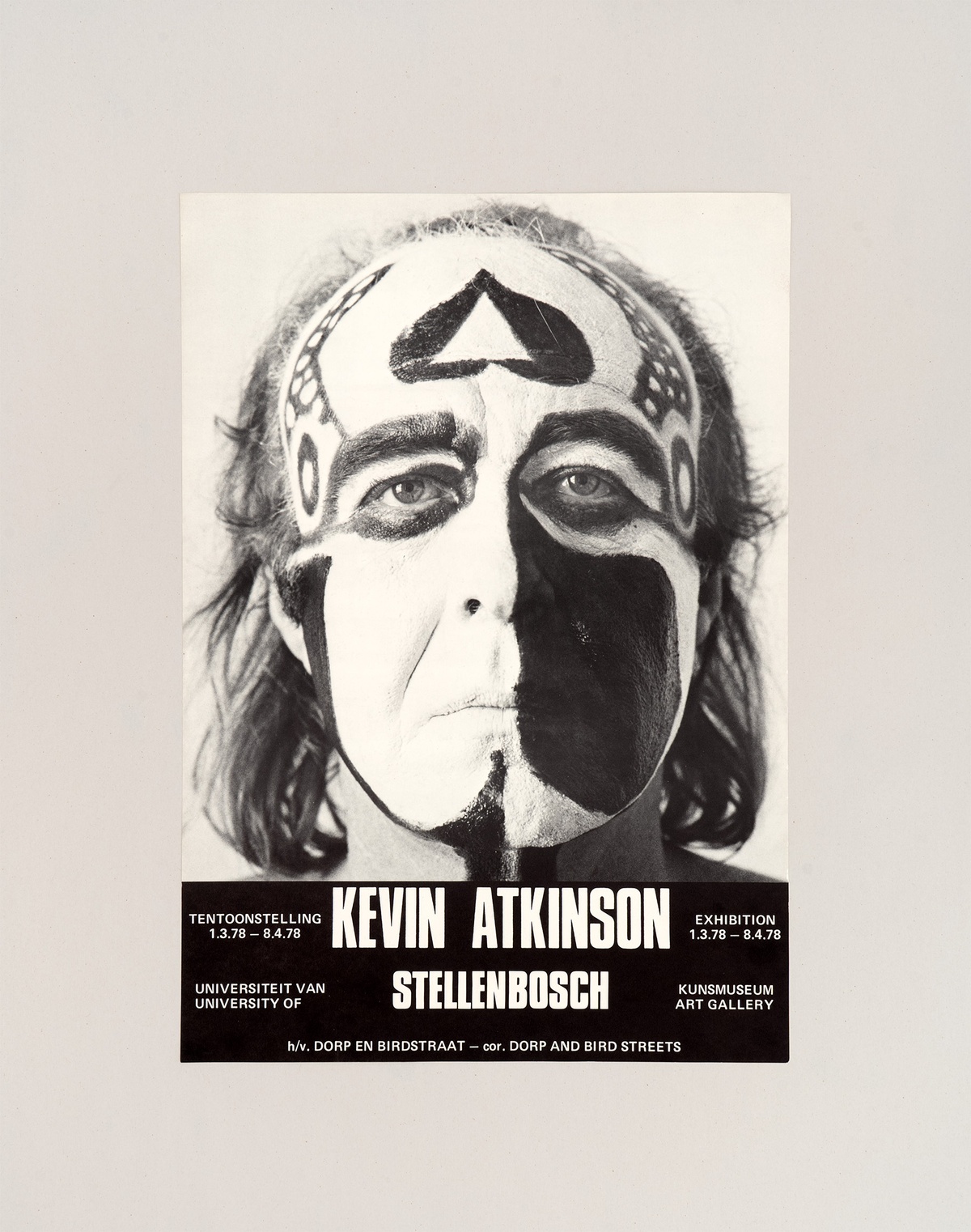

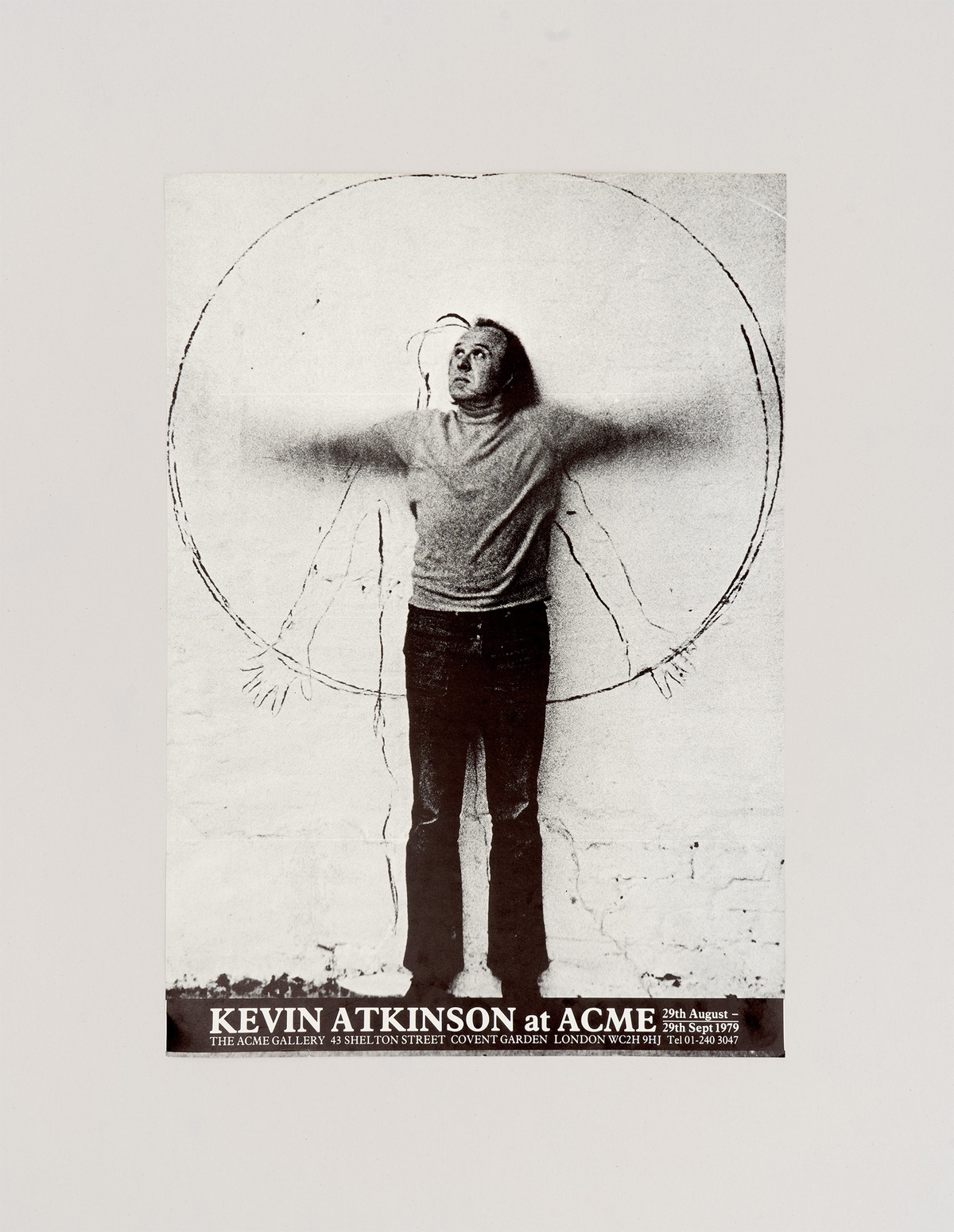

Exposure to the work of international artists and experimental practices between the 1960s and 1980s took place mainly within urban art institutions (attended by predominantly privileged, white students) through influential artists and teachers Kevin Atkinson, Walter Battiss, Willem Boshoff and Neville Dubow.

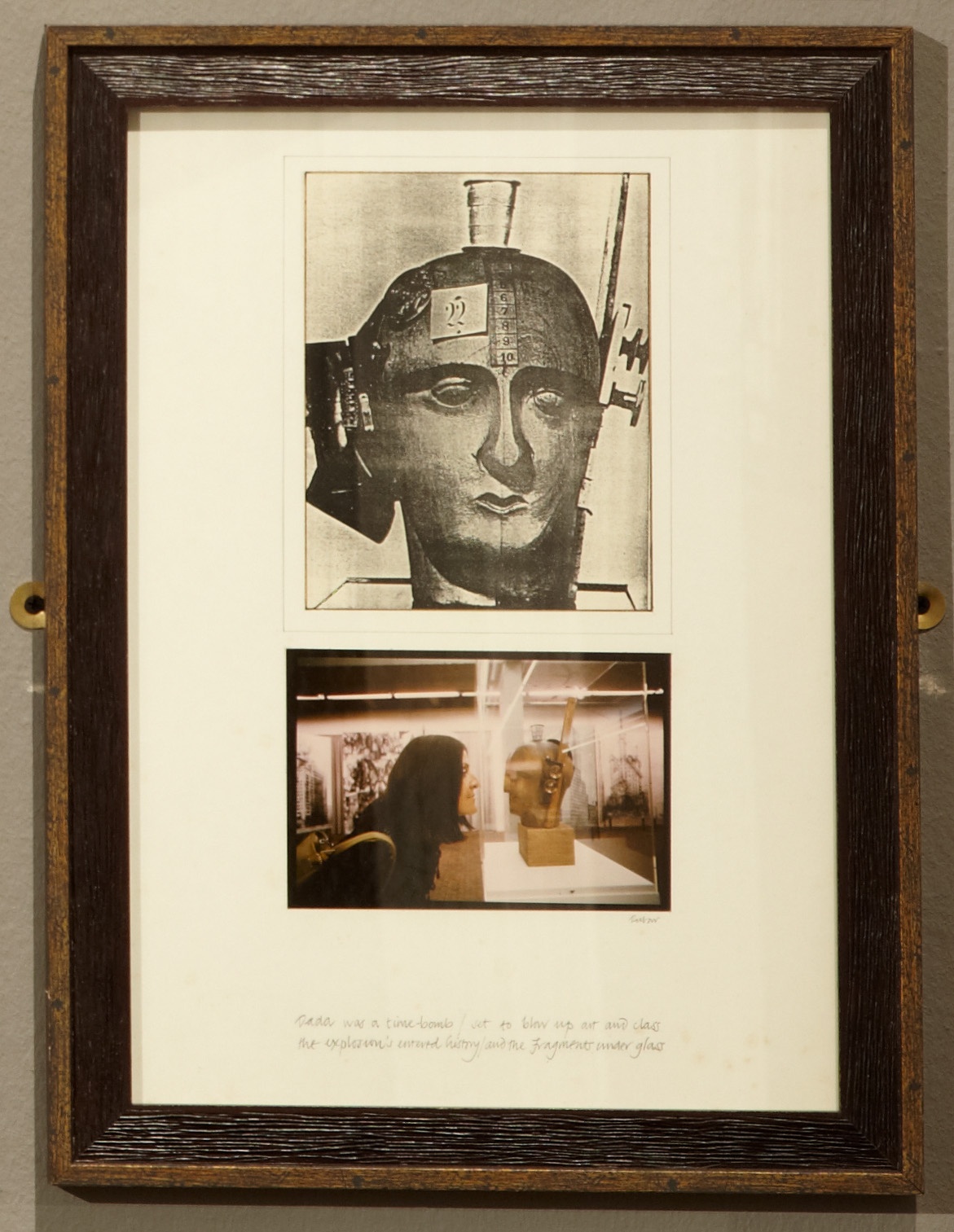

They had an exhibition of Dada art in London recently and they said that the punk people visiting the exhibition fitted in perfectly. How could one have known during Dada that punk and Dada would have come together so well?

– Walter Battiss, 1979

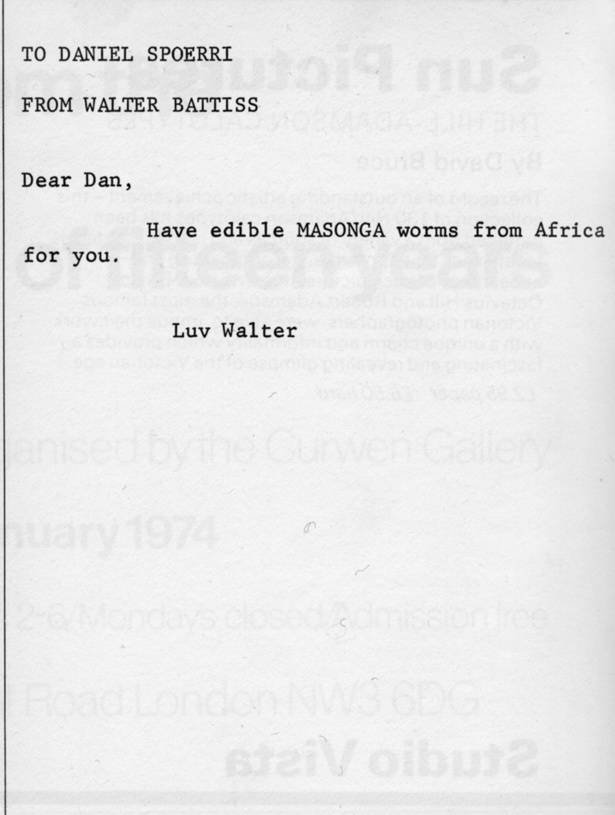

Walter Battiss maintained a friendly correspondence with Daniel Spoerri.

Jean Tinguely visited Pretoria in 1970, as a fan of the Grand Prix. He arranged to use the facilities at the Pretoria College for Advanced Technical Education (where Malcolm Payne was a student at the time) to make a sculpture as a gift for Swiss friends who lived nearby.

Risking his final art history exam, Payne made a 16mm film of Tinguely at work on the sculpture. This film made its first public appearance on Dada South? after being lost for many years.

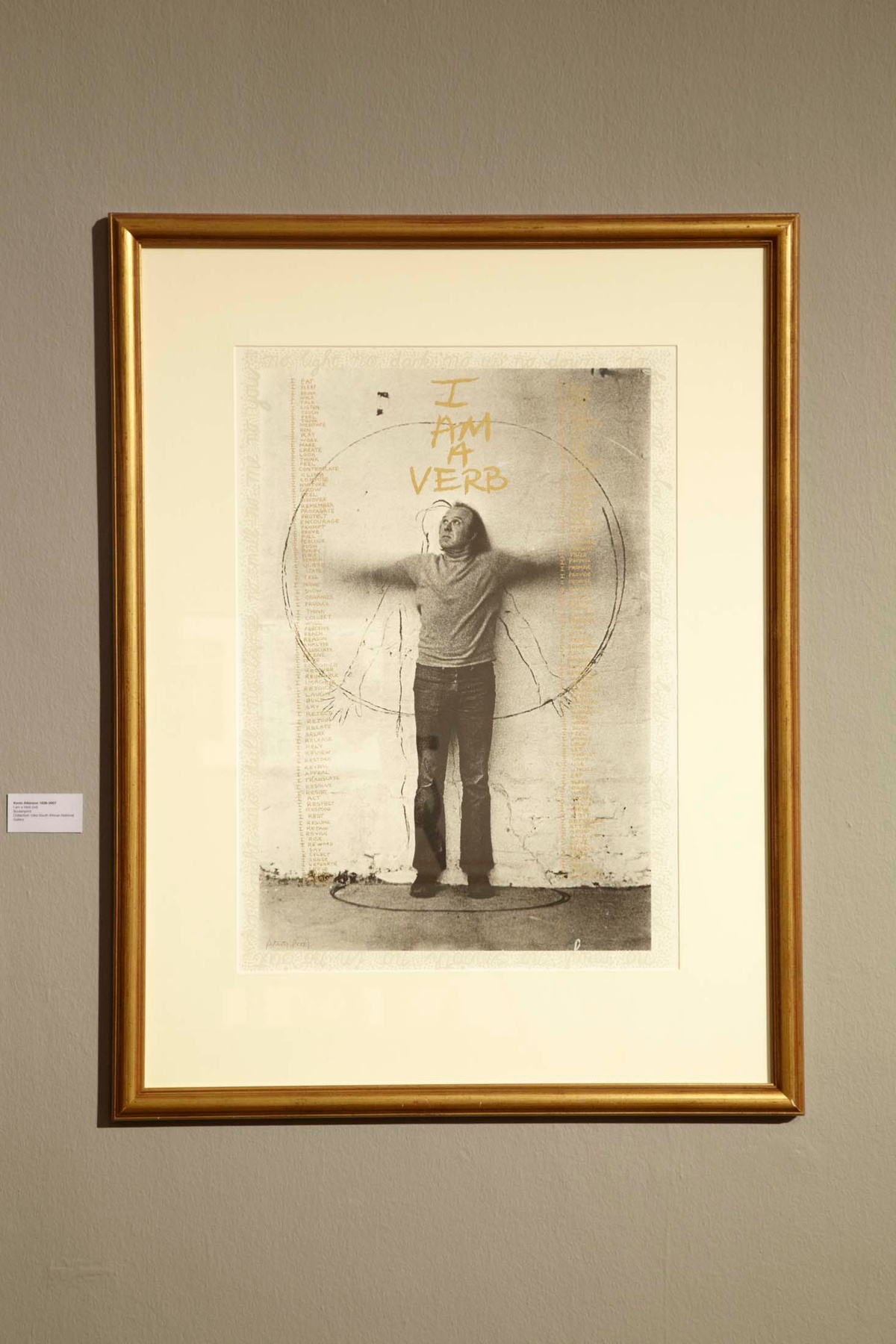

Kevin Atkinson’s interest in ‘systems art’ informed a prolific career of painting, printmaking and experimental performance; where process became a means of spiritual self-realisation.

He travelled and exhibited abroad, meeting Joseph Beuys (whom he is remembered to have described as “more a showman than a shaman”), exhibiting with Richard Demarco and having discussions with Marcel Duchamp while studying etching with Stanley Hayter in Paris in 1965.

Assemblage was a viable medium for artists who either could not afford expensive materials or for whom the materials of art should reflect the climate of its production.

Lucas Seage’s early assemblage sculptures, which are powerfully evocative of the abject lives of an oppressed black working class, earned him a scholarship to study with Joseph Beuys in Germany in 1981.

These and other ‘flight paths’ were originally mapped out by the curators in the retroactive exhibition guide commissioned by Clare Butcher in 2011. Copy-edited by francis burger, it was designed as a fold-out poster by Christian Nerf.