William Kentridge

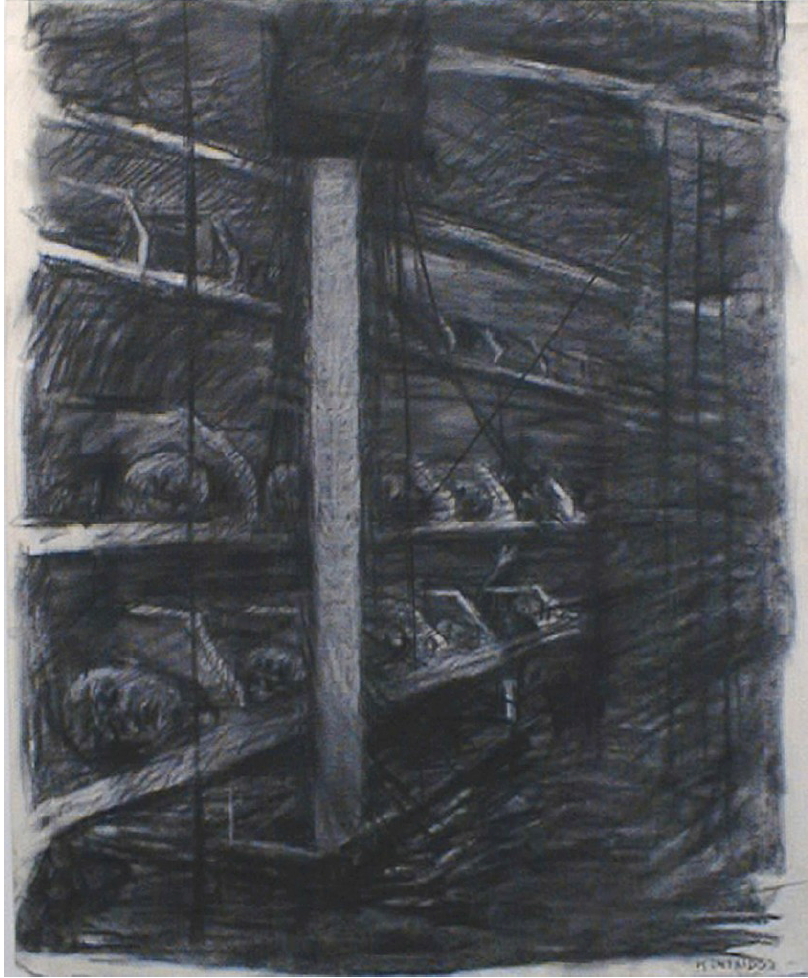

What is perhaps most compelling about Kentridge’s 'drawings for projection' is the way in which he evokes movement and mood with only the barest visual description. This drawing, from his film Mine (1991), is almost illegible as a static image, the scene darkened by a charcoal mid-tone applied across the picture plane. One can scarcely make out the heads of miners sleeping in their bunks (which appear an ominous proximation to mortuary shelves). Their layered bodies echo the strata of rocks beneath them, shown in the drawing preceding this one. Alone, however, the image is obscure. This unclear scene – the drawing’s insistent lack of clarity – is to the artist not only an aesthetic gesture but one of morality, too. “I am interested,” Kentridge says, “in a political art, that is to say, an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures and uncertain ending.”

b.1955, Johannesburg

Performing the character of the artist working on the stage (in the world) of the studio, William Kentridge centres art-making as primary action, preoccupation, and plot. Appearing across mediums as his own best actor, he draws an autobiography in walks across pages of notebooks, megaphones shouting poetry as propaganda, making a song and dance in his studio as chief conjuror in a creative play. Looking at his work, a ceaseless output and extraordinary contribution to the South African cultural landscape, one finds a repetition of people, places and histories: the city of Johannesburg, a white stinkwood tree in the garden of his childhood home (one of two planted when he was nine years old), his father (Sir Sydney Kentridge) and mother (Felicia Kentridge), both of whom contributed greatly to the dissolution of apartheid as lawyers and activists. The Kentridge home, where the artist still lives today, was populated in his childhood by his parents’ artist friends and political collaborators, a milieu that proved formative in his ongoing engagement with world histories of expansionism and oppression throughout the 20th century. Parallel to – or rather, entangled with – these reflections is an enquiry into art historical movements, particularly those that press language to unexpected ends, such as Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism.

Moving dextrously from the particular and personal to the global political terrain, Kentridge returns to metabolise these findings in the working home of the artist’s studio, where the practitioner is staged as a public figure making visible his modes of investigation. Celebrated as a leading artist of the 21st century, Kentridge is the artistic director of operas and orchestras, from Sydney to London to Paris to New York to Cape Town, known for his collaborative way of working that prioritises thinking together with fellow practitioners skilled in their disciplines (for example, as composers, as dancers). Most often, he is someone who draws, in charcoal, in pencil and pencil crayon, in ink, the gestures and mark-making assured. In a collection of books for which A4 acted as custodian during the exhibition History on One Leg, one finds 200 publications devoted to Kentridge’s practice. In the end, he has said, the work that emerges is who you are.