Michael Armitage

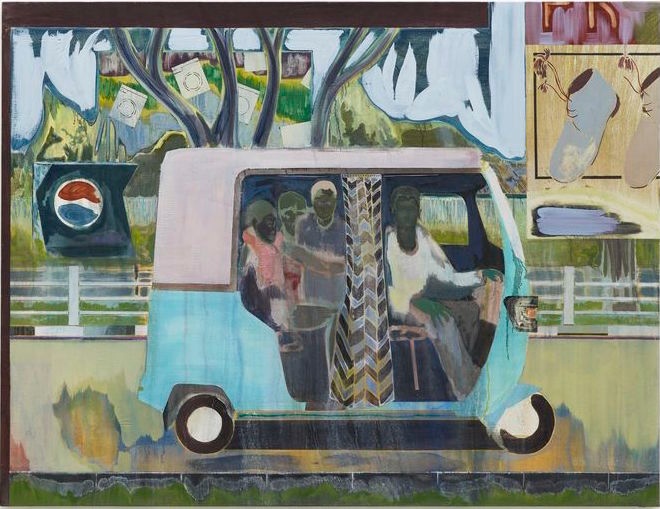

As in many of Armitage’s paintings, Search (rinse, spin, dry) has about it an unsettling undertone. The scene, however, is benign – four figures in an auto-rickshaw, a Pepsi advert in the background, a billboard, a tree – nothing to locate the unease it inspires. The paint itself lends a formal lightness, the pigment applied in thin washes and later reworked, scraped away and revised. Indeed, Armitage seldom paints thickly and uses opaque colour only sparingly. The figures’ eyeless faces look out towards the viewer without seeing, unable to return the gaze for which they are composed. Watchful – however blind – a passenger pauses, appears to be caught halfway in the action of standing up. The driver, too, hesitates; not yet stepping from the shadow of the vehicle. That their expressionless faces give no indication of their import nor the title's intent only augments the work’s ambiguity. Who is searching? And what for?

b.1984, Nairobi

Michael Armitage’s compelling and complex paintings are the confluence of Western art history and East African iconography. This unique syncretism lends his paintings their unsettling appeal as scenes at once real and imaginary, in turns sinister and celebratory. In content, however, his concerns are contemporary. Reimagining events reported in the national news as oneiric apparitions, Armitage invites magical thinking into the Kenyan body politic. With such ranging references as Post-Impressionist paintings, local mythology and current events, Armitage’s “hybrid vision,” as the critic Thomas Micchelli writes, “affirms the porousness of ethnocultural borders.” So, too, does the artist’s choice of substrate. Armitage paints in oil on lubugo, a Ugandan cloth made from mutuba tree bark, boiled, pounded and worked like leather. The sheets are then stitched together to make traditional funeral shrouds. Stretched over wooden frames, the cloth’s coarse and uneven finish, its tears and textures, lend a distinct roughness to Armitage’s paintings. The organic materiality of lubugo disrupts the painting’s surface, but far from reducing the image, each imperfection becomes instead an insistent reminder of the work’s status as hybrid; the uneven plane on which European and African visual histories collide.